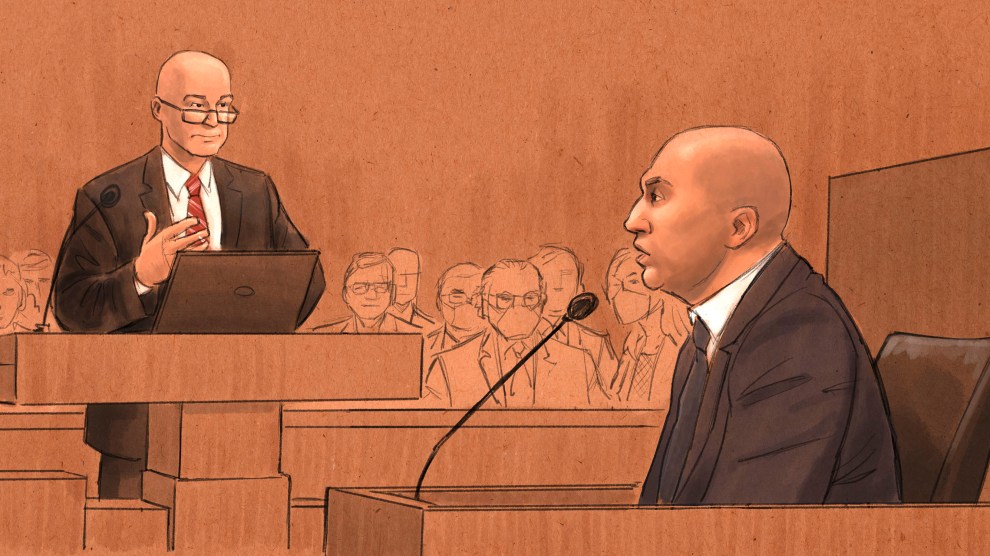

Minneapolis Police Officers Thomas Lane, left, and J. Alexander Kueng, right, escorting George Floyd, center, to a police vehicle in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020. Court TV via AP, Pool, File

Three former Minneapolis police officers were convicted on Thursday of federal charges that they violated George Floyd’s civil rights when they did not stop their colleague Derek Chauvin from murdering him.

While Chauvin pressed his knee against Floyd’s neck for almost nine and a half minutes, J. Alexander Kueng, a rookie cop, knelt on Floyd’s back. Another rookie, Thomas Lane, held Floyd’s legs down. A third officer, Tou Thao, kept bystanders back as they expressed concern that Floyd could not breathe.

During the roughly four-week trial, prosecutors accused two of the former officers, Kueng and Thao, of violating Floyd’s civil rights by deliberately failing to intervene against Chauvin’s violence. Prosecutors also accused all three former officers of violating Floyd’s civil rights by failing to provide him with proper medical care, even after he lost consciousness. “These defendants knew what was happening, and contrary to their training, contrary to common sense, contrary to basic human decency, they did nothing to stop Derek Chauvin, did nothing to help George Floyd,” prosecutor Manda Sertich told jurors during closing arguments.

After 13 hours of deliberation, a jury convicted the former officers on each count. The jury also found that the officers’ actions—and lack of action—resulted in Floyd’s death, a determination that could lead to higher prison sentences.

Policing experts said the jury’s decision to convict could set a precedent involving the extent to which police must rein in the bad behavior of colleagues. “This might be a rare occasion where a criminal prosecution will have an inordinate impact on how officers think about their jobs and how agencies think about their responsibilities,” Georgetown Law Professor Christy Lopez, who spent years investigating police misconduct for the Department of Justice, told me last week.

“A guilty verdict could help spark a change in police culture and training,” added Josh Parker, an attorney at the NYU School of Law’s Policing Project.

The former Minneapolis officers each took the stand in their defense. They repeatedly blamed the Minneapolis Police Department for providing inadequate training, and for teaching them to follow orders from superiors like Chauvin, who was the most senior officer on the scene. “I think I would trust a 19-year veteran to figure it out,” Thao testified, explaining why he did not ask Chauvin to get off Floyd.

Kueng, who had been on the job only a few days, testified that field training officers like Chauvin served as a “role model,” and that his own training barely included any mention of a duty to intervene. (Policing experts Lopez and Parker said the trial was the first time they’d ever seen federal prosecutors charge lower-ranking officers of failing to intervene against a superior.)

Because the three former officers were found guilty of civil rights violations that resulted in Floyd’s death, they could potentially face life in prison—or even the death penalty—although such severe sentences are exceedingly rare for these offenses.

Chauvin was convicted last April of murder and manslaughter in a state criminal trial and sentenced to about 22 years in prison. He pleaded guilty in December to federal charges of violating Floyd’s civil rights. Kueng, Lane and Thao also face a June trial on state charges of aiding and abetting murder.