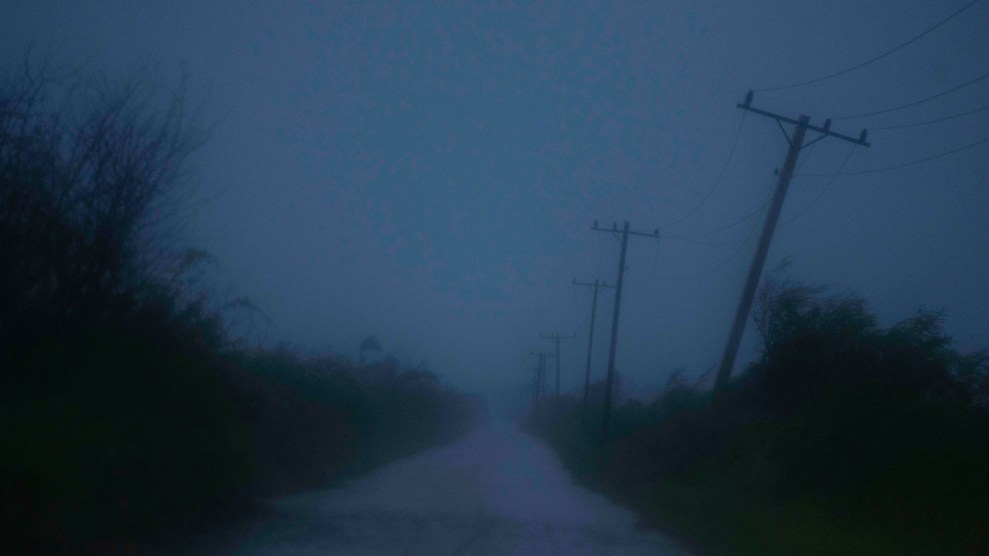

Flooded streets and homes in LaPlace, Louisiana, after Hurricane Ida moved through MondaySteve Helber/AP

As Hurricane Ida pummeled Louisiana on Sunday, blowing roofs off buildings and knocking out power to the entire city of New Orleans, hundreds of thousands of people were left stranded without air-conditioning and refrigeration in sweltering summer temperatures. Along the state’s coast, some residents remained trapped by floodwaters, begging for rescue. The storm, one of the strongest hurricanes to ever hit the United States, has drawn comparisons to Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

But as the damage grew on Sunday, the New Orleans Police Department, rather than diverting all its resources to deliver food and water to vulnerable residents, announced another priority: sending out “anti-looting” officers to protect businesses and their capital. Police Superintendent Shaun Ferguson argued that people would take advantage of the electricity outage for their own illegal gains. “Without power, that creates opportunities for some, and we will not tolerate that,” he said in a video on Facebook on Sunday, standing beside Mayor LaToya Cantrell. “We will implement our anti-looting deployment to ensure the safety of our citizens, ensure the safety of our citizens’ property.”

Just to emphasize the point: In the middle of a natural disaster, with elderly people stuck at home in dangerous heat, as boats and helicopters scour the state to find people who fled to their attics and rooftops, the cops seems less interested in helping residents access life-saving essentials than they do in criminalizing them. “[T]he city is powerless and underwater,” one lawyer with the Twitter handle Jane, Esq. tweeted, “& they’re using their resources for…anti looting. [T]his is a poster example for defund the police.”

As of Monday, the New Orleans police department had already made several arrests for stealing.”This is a state felony,” Ferguson said at a Monday briefing, according to the Associated Press, “and we will be booking you accordingly.” He said his officers were working 12-hour shifts with the Louisiana National Guard to prevent thefts. It’s “all hands on deck,” he said.

Residents objected to the police’s strategy. “[P]eople’s lives are in danger,” Ko Bragg, a New Orleans-based editor at Scalawag, tweeted, “and an anti–looting patrol, whatever dystopian bullshit that is, will put more Black lives in particular in danger.”

The police department’s response brings back memories from the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, when the media and law enforcement propagated rumors about looting and crime—misinformation that ultimately hampered relief efforts and left people stranded without basic necessities for far too long. If you haven’t listened already to Floodlines, the podcast series hosted by Vann Newkirk II about Hurricane Katrina, it’s worth your time. In the series, Newkirk II traces how the real story of people trying to keep each other alive was warped into inflammatory and often false news clips about looting and lawlessness that blamed victims for their own trauma, especially Black residents unable to evacuate from the storm. Here’s a glimpse at some more reporting in the Frontlines transcript:

Newkirk II: The city was mostly blacked out by the storm, and the media relied on partial and often secondhand reports…And a particular narrative began to emerge: chaos.

Archival news clip: Gangs of thieves who armed themselves from local stores now roam the streets, looting even the hospitals. It’s forced state officials to divert scarce resources to neighborhood patrols, hoping that a show of force will keep the looting in check.

…

Newkirk II: Reporters seemed especially interested in images of people taking TVs or Jordans. You would see the same reels of the same Black people going into the same stores, over and over.

…

Newkirk II: There were a lot of reporters trying to make a distinction between good looters and bad looters. But the fixation on looting in the first place was a distraction.

Archival news clip: This is the center of one of the great centers of America, New Orleans. Here we have a virtual refugee camp with thousands of people waiting for some sort of help—medical, food, water, you name it. And then over there, the police. Scores of police officers are concerned about one looter who’s in that supermarket.

Newkirk II: It was like all the suffering was invisible to some people. All they could see was crime.

After Hurricane Katrina, as false rumors spread that the Superdome where people were sheltering had turned into a war-zone of rape and murder, journalists reported that hundreds of police officers in New Orleans were called away from their rescue work to deal with “lawlessness.” The paranoia about crime got so intense that the Red Cross waited weeks to come to the city. Some trapped residents told Frontlines that it felt dehumanizing to see officers standing guard with rifles rather than delivering aid. “So I didn’t understand why they was doing that instead of being down here helping us or bringing food and water. Like, why are we being treated like dogs?” said Le-Ann Williams, then a 14-year-old girl whose family took shelter at the city’s convention center. ProPublica reported that a police commander told his officers they had permission to shoot “looters.”

And sure enough, New Orleans officers gunned down at least 10 people after the storm. In one instance, officers responding to a distress call opened fire on two groups of Black people who were not armed and had been crossing the Danziger Bridge in search of food and water, injuring at least four people and killing two, including a man with developmental disabilities who was shot in the back.

Hurricane Ida’s landfall came exactly 16 years to the day after Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast. But as Police Superintendent Ferguson urged New Orleans residents to avoid crime and “be vigilant,” and as his officers booked people into jail for alleged theft, it appears that even after all these years, law enforcement in the city haven’t changed much.