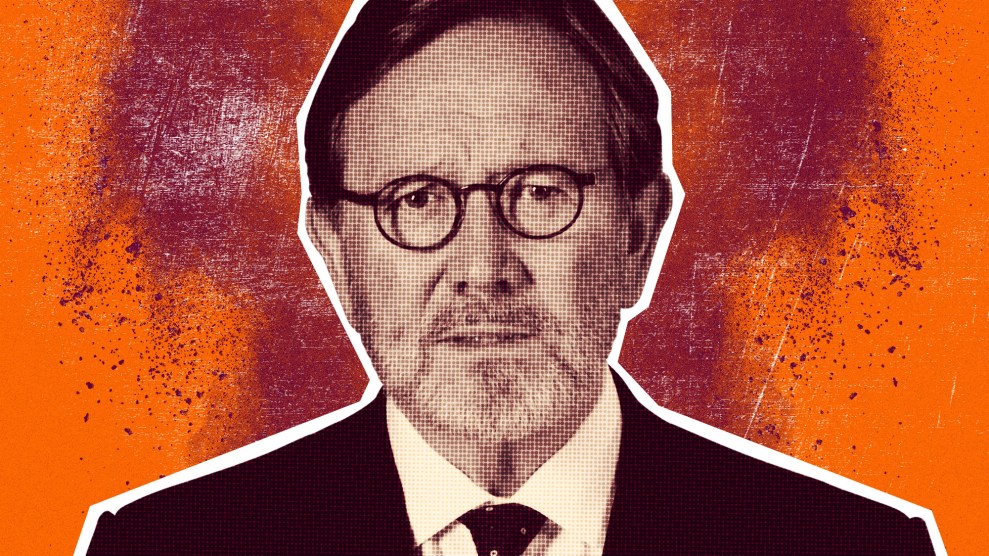

Then-Rep. Mike Pitts speaks on the floor of the South Carolina House during debate over a bill calling for the Confederate flag to be removed from the statehouse grounds in 2015.John Bazemore/AP

This story was published in partnership with ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

When South Carolina lawmakers confirmed a batch of new magistrates this year, one nominee stood out from the pack: Mike Pitts.

The former state House member had made a name for himself in Columbia as a staunch defender of the Confederate flag, and on Facebook he has penned anti-immigration screeds and used racially charged language. In May, for example, he posted a photo of New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, an African American Democrat running for president. His caption: “Cory Booker alway [sic] looks like he just hit crack real hard.”

None of this, however, prompted any discussion in June, when the state Senate confirmed Pitts along with 33 other nominees for the lower courts.

Unlike South Carolina’s felony and appellate court judges, magistrates are not subjected to legislative hearings before lawmakers sign off on their appointments. In fact, there’s rarely any public debate at all. Nominations typically sail through the upper chamber with a single voice vote.

Although magistrates oversee mostly misdemeanor matters, their authority is substantial; each year, they decide hundreds of thousands of cases, including criminal ones that can send someone to prison for months or saddle them with thousands of dollars in fines.

But the confirmation process allows new recruits to escape public scrutiny and sitting magistrates to remain on the bench even after they’ve been disciplined for misconduct, an investigation by The Post and Courier and ProPublica found.

Some appointees have gone on to make racist and sexist comments from the bench.

Magistrate Willie Bethune in Clarendon County, for example, said a defendant was attractive and asked her to show off her bellybutton. He was later accused of pressuring that woman into giving him sexual favors. While he denied the charges, he resigned amid an investigation by the Office of Disciplinary Counsel, which polices judges and lawyers in the state.

Charleston Magistrate James Gosnell, who is white, used a racial slur during a bond hearing for an African American defendant and was reprimanded by the disciplinary office; he described it as an ill-considered attempt to get the man to change his path in life. The judge remains on the bench today, reappointed in May.

Beaufort County Magistrate Peter Lamb called crack cocaine “a black man’s disease” and later resigned. As part of an agreement with the state Supreme Court, he acknowledged misconduct in that instance—and in others—and promised to never seek judicial office again, without permission.

The Post and Courier and ProPublica found Pitts’ Facebook page while researching the backgrounds of all 319 magistrates in South Carolina. Like many magistrates, he doesn’t have a law license; to qualify for nomination to the lower courts, applicants need only to earn an undergraduate degree and pass a basic competency exam. Pitts served as a police officer in South Carolina for a decade before retiring in 1987. Several of his posts appear at odds with key tenets of the state’s judicial code of conduct, which stresses impartiality and strict avoidance of words or actions that demonstrate bias or prejudice.

In a November 2017 post, he complained about people “from the Middle East” in Walmart and wrote, “after being subject to this incident I now support shutting down all immigration until we stop the demise of our culture.” And he has been recently photographed wearing a shirt reading, “Welcome to America Learn the Damn Language!”

In another post, Pitts criticized transgender people, saying “they aren’t sure what the hell they are.”

Pitts, a Republican who recently took the bench, didn’t respond to messages left by phone and email.

Civil rights advocates condemned Pitts’ remarks and called for his removal.

“A person with such racist and xenophobic views should not be placed in a position that will inevitably impact the lives of citizens in a diverse community,” said Ibrahim Hooper, national communications director for the Council on American-Islamic Relations. “Magistrate Pitts should be removed from his post in order to maintain the objectivity and impartiality of the South Carolina judicial system.”

Brenda Murphy, president of the South Carolina chapter of the NAACP, said her group is “totally against” the idea of Pitts donning the robe. “We would not want someone who has made those comments appointed as a magistrate in a local community,” she said.

Some state lawmakers also questioned Pitts’ fitness for the bench.

Republican state Rep. Gary Clary, a former state circuit judge, said the posts could be “grounds for recusal” in cases where people of color or transgender people appear before Pitts.

“That’s the reason judges don’t normally have Facebook and Twitter accounts,” Clary said. “You are supposed to be fair and impartial.”

State Sen. Dick Harpootlian, a Democrat, went further.

“None of us were aware of these posts, or his ethnic and racially insensitive comments, which I think disqualify him as a fair or impartial judge,” Harpootlian, a longtime trial lawyer, said after The Post and Courier described Pitts’ posts.

“If I was Muslim or of Middle Eastern descent, I would be fearful of appearing in front of him.”

A spokesman for Gov. Henry McMaster said no one brought the posts to his attention before McMaster, a Republican, signed off on Pitts’ appointment this year. The governor declined to expand on the issue.

Chief Justice Donald Beatty of the South Carolina Supreme Court, who oversees all of the state’s court officials, also declined to comment.

A Republican who served 13 years in the legislature, Pitts has long stoked controversy. When state leaders pressed to remove the Confederate flag from Statehouse grounds in 2015 after the mass shooting at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church, Pitts was a chief opponent.

The following year, he proposed legislation to require journalists to register with the state government or face fines. And in 2018, Pitts co-sponsored a bill requiring South Carolina lawmakers to consider seceding from the Union if the federal government “confiscates legally purchased firearms.” Neither measure passed.

More recently, his bid to run the state’s land conservation agency fell apart amid concerns that Pitts, an ex-cop, wasn’t qualified for the job. Critics said the move was a political gift to Pitts following retirement from the House last year. He withdrew from consideration, saying the “aggressive inquisition” he faced during a confirmation hearing had harmed his health after a heart attack last year. “I tired quickly and realized that my cognitive skills have been affected,” he wrote in his withdrawal letter.

But within months, Pitts was a candidate for a magistrate seat in Laurens County, a mostly rural area in the upper portion of the state, about an hour from the Blue Ridge Mountains. A quarter of the area’s residents are black. “I have applied for jobs in several different locations in private industry and other places,” he told the Greenwood Index-Journal. “I’m not ready to retire and I’m either too old, too experienced or too hot a potato.”

This time, with the backing of his Republican colleague, state Sen. Danny Verdin, he faced far less scrutiny. “The bottom line is, this is a job I’m well qualified for,” Pitts told the Index-Journal, citing his law enforcement background.

Unlike any other state in the country, South Carolina allows state senators to hand-pick magistrate judges. Because they are considered local appointments, senators almost never question selections outside their delegation. The governor signs off on the appointments, but largely defers to the legislative chamber.

The process for selecting magistrates varies from county to county.

In the Charleston metro area, for example, the eight-member senate delegation convenes public meetings to review and discuss the qualifications of potential candidates. Greenville, with seven senators, operates much the same way.

But in a dozen of the state’s 46 counties, including Laurens, the selection of magistrates lies in the hands of a single senator.

That meant Pitts only required Verdin’s backing.

The Post and Courier asked the lawmaker about Pitts’ Facebook posts, but Verdin declined to review them.

“That’s not necessary,” he said. “I will have no comment.”