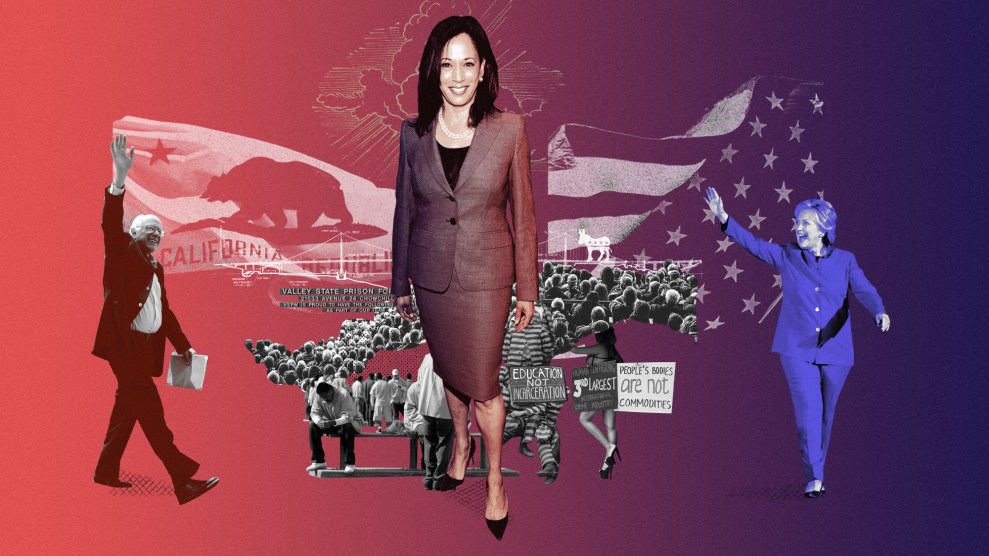

MSNBC anchor Ari Melber, Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Ca.), and Voters Organized to Educate advisory board member Rev. Vivian Nixon discuss criminal justice reform at Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site.Jason E. Miczek/AP Images for Voters Organized to Educate

Dorsey Nunn traveled from California to Pennsylvania for it, but very few of the sprawling field of Democratic presidential candidates bothered to make the same commitment. Of the top tier, only Sens. Kamala Harris and Cory Booker came. (Billionaire Tom Steyer joined too.) “It was interesting that the two people that thought we were important enough to talk to were the two black people running for president,” said Nunn, referring to the formerly incarcerated people who moderated and attended a first-of-its-kind presidential town hall on Monday.

The criminal justice advocacy group Voters Organized to Educate, which coordinated the event, invited the 10 Democratic candidates who qualified for the third debate to come discuss criminal justice reform at a former prison in Philadelphia, to speak directly to formerly incarcerated people and their family and friends. The tens of millions of Americans with conviction or arrest records, said Nunn, are “the sleeping giant in your living room that nobody is talking to.” Nunn himself was incarcerated in California for most of the 1970s and now runs a grassroots criminal justice advocacy group called All of Us or None that has been crucial in spreading Ban the Box policies to help people find jobs after prison.

His organization hosted a watch party on Monday morning at its Oakland headquarters with about a dozen people, some of them formerly incarcerated. A few sipped coffee and munched on pastries as the show got started, sighing when the YouTube livestream repeatedly stalled. Sitting in the second row of folding chairs, Mark Fujiwara, who spent a year in the nearby San Quentin Prison and now works with Nunn, waited patiently for it to resume. By engaging directly with formerly incarcerated people, he said, the candidates would be taking an important step “to validate our humanity.”

Except it was far from all, or even many, of the candidates. Most of the leading contenders, including former Vice President Joe Biden and Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, instead went to another criminal justice forum over the weekend at a historically black college in South Carolina, livestreamed to a bigger audience by major news outlets. (Harris and Booker went to that one too.) But their absence at the first town hall organized by formerly incarcerated people could send a message, organizers say, that they aren’t placing a top priority on constituents who have been directly affected by the criminal justice system, especially low-income people of color. “It’s telling—they don’t see us as a good investment,” said Steven Czifra, who came to the Oakland watch party with his son. “This is a chance to a have a conversation with formerly incarcerated people, and we have three candidates showing up? I’m sorry, that is unacceptable,” Booker said at the event at Eastern State Penitentiary, which was presented in partnership with The Marshall Project and NowThis News. “This is not a side issue.” (Sanders offered to participate via a video call, but the organizers said it wasn’t feasible; former Housing Secretary Julián Castro spent part of the day visiting with incarcerated people at a DC jail.)

“The other candidates who happen to not be African American are going after the traditional path to gaining the African American vote, going to historically black colleges, going to black churches,” added the Rev. Vivian Nixon, one of the town hall’s moderators, in a phone interview before the event. The weekend forum at Benedict College in South Carolina, where President Donald Trump gave a keynote address and received an award, had a much bigger turnout but largely engaged with college-educated African Americans. As Nixon told me, “They figure they are going to get a bigger bang for their buck. They believe people who have been involved in the criminal justice system don’t vote, which is simply not true.”

Most states restrict voting rights of people who are serving time in prison, and some restrict the rights of people out on parole. But only two states, Iowa and Kentucky, permanently disenfranchise all people with felony convictions. In the rest, formerly incarcerated people can eventually participate in elections. And they’re no small voting bloc: There are more than 2 million Americans currently in prison. More than 70 million Americans have been arrested on felony charges or incarcerated. And 1 in 7 American adults have an immediate family member who has been incarcerated for at least one year. “I don’t understand why people running for office at every level don’t consider us a serious voting bloc,” said Nixon.

That’s not to say Democratic candidates aren’t genuinely trying to push the needle on criminal justice. Most of the front-runners have proposed reforms that would have been unthinkable a decade ago, like abolishing private prisons and ending mandatory minimum sentences, cash bail, and the death penalty. But some are also under scrutiny for supporting more punitive policies in the past: Biden, for his role in writing the 1994 crime bill; Sanders, for voting for it; and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, for failing to hire more black police officers.

Harris and Booker are no exception. The California senator has described herself as a progressive prosecutor who made the system more fair, but critics point to policies she advocated in the past that led to the incarceration of more people of color. At the town hall Monday, when asked whether she believes she went too far with any of her decisions as San Francisco district attorney or state attorney general, she largely dodged the question, saying yes but not going into specifics. At the Oakland watch party, some people groaned as she said she became a prosecutor so she could work from within the system to improve things. “Trying to get on top,” one person muttered. “She’s a cop,” said Fujiwara, adding that he didn’t trust her. A handful of people got up to leave the party as she spoke.

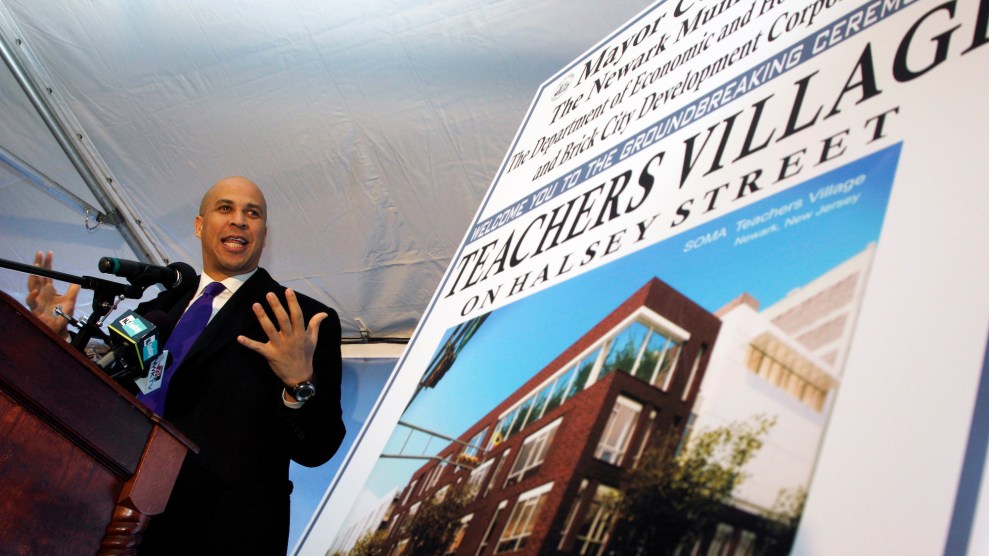

Booker, who spoke last at the town hall, also addressed his own record as mayor of Newark, New Jersey, specifically his initial zero-tolerance policy on crime. After the ACLU complained about stop-and-frisk policing and asked the Justice Department to oversee the city’s police force, Booker changed his views and began to embrace more progressive reforms. “We thought we were doing a good job, but we were not,” he said at the town hall of his experience with police accountability in Newark. “I learned the hard way that this idea of policing, it’s deep, it’s endemic, it has problems. Even people who think they are doing the right thing most likely are not.” At the watch party, some who left the crowd during Harris’ and Steyer’s segments came back for Booker. Fujiwara, for one, seemed impressed, saying he was encouraged by the senator’s proposal to use federal incentives to encourage investment in restorative justice programs.

Some moderators weren’t surprised that Booker and Harris were the ones who ultimately showed up. Despite their history, both senators have prioritized criminal justice reform in the Senate and made it a focal point of their presidential campaigns in a way that few others have. “Kamala and Cory, being part of the African American community, have been exposed to more kitchen table conversations with people directly impacted by mass incarceration,” said Nixon. “Just by nature of them living in those communities, caring about those communities, they have a perspective that I don’t think the other candidates have. The reason we wanted to have this forum was to give those candidates a little bit of that perspective.”

The only other candidate in attendance Monday was Steyer, who founded NextGen, a progressive advocacy group. He did not participate in the weekend forum at Benedict College, and is less known for his positions on criminal justice. At the town hall, he showed support for ideas endorsed by many leading candidates, like ending mandatory minimums and making it easier for formerly incarcerated people to find employment. But a moderator pointed out that in 2004, his hedge fund invested heavily in the Corrections Corporation of America, now called CoreCivic, one of the country’s biggest prison companies. Steyer, who says he opposes for-profit incarceration, responded that the investment was a mistake and the hedge fund sold the stock two years later.

The room at the Eastern State Penitentiary, now a museum, was big enough for only about 65 audience members, though there were at least 130 watch parties across 20 states, according to Voters Organized to Educate. Among those in the audience in Philadelphia was Yusef Salaam of the Central Park Five, who was wrongly convicted of rape and incarcerated in New York as a teenager, and later exonerated; Reginald Dwayne Betts, a poet and memoirist who was sentenced to nine years in prison as a teen; and chef and best-selling author Jeff Henderson, who served time for a cocaine offense. Organizers said one of their main goals was to help the politicians relate to people with criminal histories on a more personal level.

Though its audience may have been smaller, the town hall was at least one step toward accomplishing that goal. “For the most part,” said Dorsey, “I’m extremely proud and encouraged that a few candidates have shown up and decided to talk with us.” Nixon added, “When you are proximate to people who have experienced the thing you’re trying to legislate about, you are much more likely to make legislation that has a positive impact on those communities.”

Still, some at the watch party were skeptical. Lee “Taqwaa” Bonner, who was released from prison a few years ago after about three decades behind bars, and who’s now a housing advocate with Dorsey’s organization, said that when it comes to politicians, even presidential candidates who hit all the right talking points, he’s cautious: “From what I’ve been observing, they say one thing and do another.”