Josh Edelson/AP

On a rain-soaked afternoon in Napa Valley this spring, a somber crowd of about a hundred gathered inside the Yountville community center, located on a tree-lined street in the town’s business district. Many residents from the wine-country town of about 3,000 held white roses and wore purple bracelets bearing the words “Never To Forget.” “A year ago, something unimaginable happened,” Steve Rogers, the town manager, told the crowd. “Talking with a lot of our residents, neighbors, and friends, this was a very challenging moment. It changed Yountville.”

On March 9, 2018, a small group of staff members and residents of the nearby Pathway Home, a specialized residential treatment facility for military veterans, had gathered for a party inside the building when a 36-year-old Afghanistan war veteran showed up, uninvited and armed with two guns and a supply of ammunition. Albert Wong had been dismissed from the Pathway program two weeks earlier for threatening to shoot staff members, according to a civil lawsuit filed by a victim’s family. He ordered the partygoers out one by one, until three women remained—Christine Loeber, Jennifer Gonzales Shushereba, and Jennifer Golick, all of whom had worked closely with Wong on his treatment. Responding to a frantic 911 call from one of the fleeing staff members, police raced to the scene within a few minutes and began attempting to communicate with Wong. But less than 15 minutes into the hostage crisis, Wong had fatally shot his three former caretakers and himself.

It was a devastating blow from which the community was still reeling a year later. At a Yountville coffee shop the morning of the memorial gathering, I met with Larry Kamer, a former Pathway board member who became the de facto spokesperson for the organization after the shooting. A temporary power outage from the stormy weather left us sitting in only the faint light coming through the storefront window. Nearly everyone in Yountville had some kind of tie to Pathway, including Kamer, whose wife was communications director for the home—and was the last hostage Wong released before he opened fire.

“You have the incident itself, which was horrible enough,” Kamer said, recalling how frightening and painful that day was. But as with other venues hit by mass shootings, keeping the place open was just too much to bear. The home was permanently closed less than six months later, with residents transferred to other programs. Now, the aftereffects of the shooting compounded the trauma of those under care at the time. Perhaps worst of all, Kamer said, was that “something like that could happen to the very people who are at ground zero treating these vets.”

That unthinkable loss has Kamer and his colleagues seeking to continue the mission of the Pathway Home, which dates back a decade and was highly regarded among veterans’ affairs experts as among the most effective treatment programs in the country for troubled soldiers. A small, community-focused program that was housed on the grounds of the largest veterans’ home in the United States, the Pathway Home was seen as a successful model, working with about two dozen men at any given time. It became known for trauma-informed care that was effective, built on a combination of intensive therapy and the teaching of key skills for reintegration into civilian life.

The three women killed were at the heart of that work, Kamer said. Christine Loeber, Pathway’s executive director, had started off in social work and transitioned to veterans’ care, working with female vets in Boston before coming to California. “It really is a calling for some people,” Kamer said. “It was a deliberate choice she made to come out and do this work.”

Jennifer Gonzales Shushereba was a clinical psychologist at Pathway. She was six months pregnant at the time of the shooting. Her husband told a San Francisco reporter that she had often seemed drained when she came home from work, but that the fatigue was no match for her passion. Her father said she particularly liked working with vets because she “felt like they wanted to be helped.”

Jennifer Golick, who had joined Pathway as the clinical director six months before the shooting, had worked with troubled boys in Petaluma, California. She was known for her ability to connect with the vulnerable, according to a family friend who told the San Francisco Chronicle that Golick “could figure people out really quick.”

From left: Golick, Loeber, and Gonzales Shushereba

Muir Wood AFS; Pathway Home; PsychArmor

Wong had been receiving in-patient psychological treatment at Pathway, and like the other residents he had access to various resources of the tight-knit town surrounding the home, such as job training and social outings. But as the community still grapples with what went so wrong in Wong’s case—the subject of ongoing civil lawsuits over who may be responsible for the carnage—the tragedy also points to the ongoing risks of violence and suicide among a relatively small but significant population among America’s 3 million post-9/11 war vets.

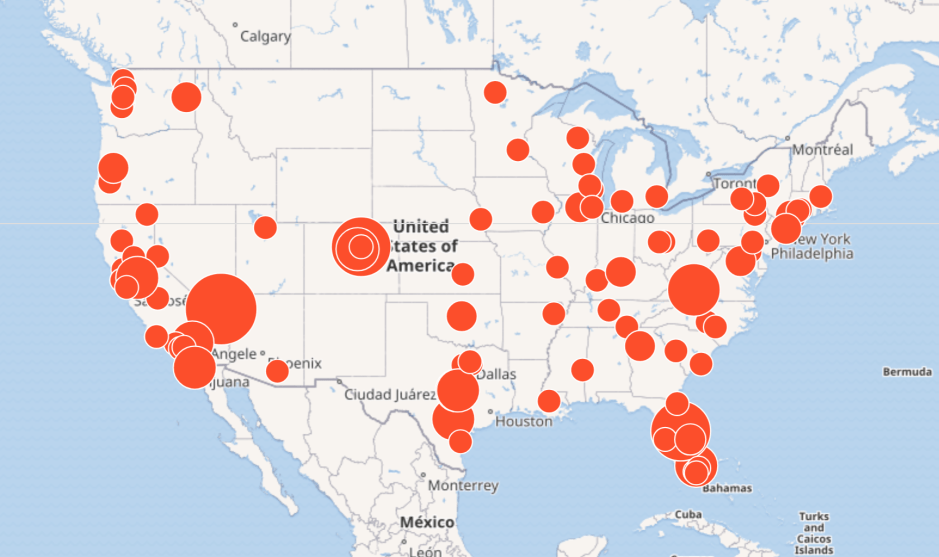

According to Mother Jones‘ in-depth database of mass shootings, of the 55 mass shooters who have struck in the United States since 2012, 14 were military veterans, or more than a quarter of that group—an outsized percentage given that vets are less than 10 percent of the total population. In addition to the Yountville perpetrator, other suicidal attackers included a former Marine who opened fire at a bar in Thousand Oaks, California, last November; an Air Force veteran who massacred churchgoers in rural Texas in 2017; and an Army vet who gunned down five Dallas police officers in 2016.

The vast majority of military veterans do not commit violent attacks. But according to experts, the link with military service among a small group of mass shooters underscores pervasive mental health problems and suicidal ideation among vets, and an urgent need for better veterans’ care in this era of prolonged US-involved wars. “The fact of the matter is, [veterans] are most likely to harm themselves if they’re going to harm anyone,” said Jeremy Butler, CEO of the nonprofit Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. “The vast majority of the time, they’re going to be the ones running to help.” Studies show that veterans are far more likely to struggle with issues like homelessness and depression and ultimately be a risk to themselves: According to VA statistics, veterans comprise eight percent of the US population but account for 14 percent of suicides nationally.

For the minuscule number who may be thinking of committing a mass shooting, the danger can be exacerbated by weapons know-how and access to guns. Wong was outfitted for battle when he attacked the Pathway Home, armed with a shotgun, semi-automatic rifle, and extra ammunition and wearing ear and eye protection.

A more robust system should be in place for handling troubled vets before America repeatedly sends its troops into war zones, said Butler. “What we’ve seen from these post-9/11 conflicts is that we’re not giving enough thought to what has to take place once you bring the service members home—what kind of treatment and services they’re going to need, and how we’re going to fund that.”

The Pathway Home, which opened its doors in 2008, was part of a solution. It was initially funded by a private grant and later relied on local fundraising. A 2014 documentary followed a group of Pathway residents, and a 2017 film depicted the story of a vet who had gotten help for his PTSD at Pathway and later became a peer counselor there himself. A key for the organization was its strong local support; someone in the community would hear from Pathway staff that a vet needed help buying a car, for instance, and would take that person to the dealership.

“A lot of these guys come back [from multiple tours], and they haven’t had to balance a checkbook in a long time,” Kamer told me, as we sat in the dim light of the café. Substantive opportunities to get vocational training or study at a local community college were “very, very helpful to these guys,” he said, adding, “Pathway would say jump, and people in the community would say, ‘How high?'” Over time, the organization was able to alleviate the stigma and worry often associated with troubled war vets. “Word got out that Pathway was a good thing,” Kamer said.

Since last summer, Kamer and former members of Pathway’s board have been working to spread Pathway’s mission elsewhere. At a VA center in Martinez, a town about an hour south of Yountville, veterans participate in a treatment program similar to the one used by Pathway. With the assistance of a journalist who focuses on veterans’ health care, Pathway leaders are creating a guide for other veterans homes to implement their own community-centered programs in this mold. And they hope to galvanize Martinez residents, as in Yountville, to visit the home often and forge connections with residents.

The goal now for Kamer and other local leaders, he said, is to “keep the conversation alive here, difficult though it may be, about these vets.” As fellow Pathway board member Dorothy Salmon said at a memorial service after the shooting, “This has been our mission for 10 years and it will go on.” Speaking of the three women killed, she emphasized: “This is their gift and this is their legacy, that we keep this going.”