This story was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system.

Leona Godfrey was sitting down to dinner at a TGI Fridays in Orange, Connecticut, in December 2013 when she glanced at a television and saw her little brother’s name on the local news. Davon Eldemire had tried to rob a small grocery store, shooting and injuring the owner. “I was devastated,” Godfrey recalled. “What was he thinking? I couldn’t eat.”

He was 20. She was ten years older and had helped raise him, looking on in shame as he piled up an arrest record for drugs, larceny, and shooting an illegal gun in public. Lately, he had been talking about buying his daughter, Saniyah, a bed for Christmas. She figured the robbery was how he had planned to get the money. What he got instead was Christmas in jail, and then 14 years in prison for assault and attempted robbery.

At first Godfrey didn’t visit, less out of anger than inertia. But early last year, their mother, Linda Godfrey, started begging Leona to come see something neither would have expected: the prison seemed sincere about helping Davon turn his life around. Linda had attended a presentation by John Pittman, an older prisoner who was going to be Davon’s mentor, pushing him away from gangs and towards planning for his life after release. Linda was deeply moved. “He touched my heart,” she said of Pittman.

Davon had been selected for a pilot program called TRUE at Cheshire Correctional Institution. The effort represents the edge of experimentation for prison officials trying to help a population—young adults, roughly 18-25—long known as the most likely to end up in prison and to commit more crimes after their release. Public officials have recently started to listen to neuroscientists who say the developing brains of young adults are still prone to impulse. They’re not juveniles under the law, but like younger teens, their minds are plastic and receptive to change. Vermont is raising the age of who is considered a “youthful offender” to 21, Washington is allowing certain crimes committed by those up to 25 to stay in juvenile courts, legislators in Texas are studying how “gaps in services” contribute to crime among 17- to 25-year-olds, and Chicago and San Francisco have set up special courts for young adults.

Uniquely, Connecticut is focusing attention on young men who are already in prison. Inspired by a youth prison in Germany, the state has placed about 50 of them in a single unit, along with a small group of older prisoners who serve as mentors. Many American prisons have classes, jobs, and rehabilitative programs, at least on paper. But in the TRUE program, the older prisoners have been granted the trust and latitude to develop a radically different environment, somewhere between family and reformatory, with strict rules, incentives and long days of work and study. The young men go through a series of stages, learning to confront their pasts, to be vulnerable around their peers, to resolve conflicts through communication instead of violence, and to master basic life skills they may have missed, such as managing a personal budget.

It’s too soon to tell what this experiment will yield. The program is tiny, encompassing only two percent of their age group in the Connecticut prison system, and much of its early success relies on the particular men involved. Though it has curbed violence inside the prison—and though none of the nine men released from the program have been incarcerated for new crimes—the real test will come over the next few years as the department tries to expand the program and participants return home in larger numbers. Though researchers see promise in the idea of using mentors, it can be tough to isolate their effect in programs such as TRUE, where prisoners are getting lots of different support services all at once. “The literature on mentoring is limited,” said Angela Hawken, a New York University professor who studies programs that try to keep people from returning to prison.”

There’s still a lot to be learned about whether this approach works.”

Davon Eldemire

Karsten Moran / The Marshall Project

But despite the lack of a track record, the Connecticut program is proving influential. The Vera Institute of Justice in New York, which helped Connecticut develop TRUE, is setting up similar young adult programs at the jail in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, near Boston, and in the South Carolina Department of Corrections. Even as the rhetoric out of the White House tends toward the punitive, many state prison leaders are openly championing rehabilitation.

That’s at the macro level. But zoom in and rehabilitation becomes personal: In the TRUE unit, the mentors try to get each of these young men to explain what brought them to prison and to articulate why they want to change. For Davon Eldemire, it came down to his daughter. Soon after he was incarcerated, he was chatting with his sister Leona by phone when he heard Saniyah pipe up in the background.

He started to choke up. “What have I done?” he said.

Three years ago, Connecticut corrections commissioner Scott Semple spent a week touring prisons in Germany, where incarcerated men and women cook their own food and wear their own clothes in an environment which, except for the razor wire, looks like a liberal arts college. A dozen other states have sent similar delegations to European prisons, and officials are starting to copy bits and pieces of what they have seen there. Semple, himself a former corrections officer, was particularly struck by Neustrelitz Prison, in Germany’s northeastern countryside, where nearly 200 young men and women live together on a farm, exposed to intensive therapy while raising animals and working in a welding shop. The environment was foreign, but local German officials discussed their challenges in a way that felt familiar. “This is the place for violence because they are young, they are aggressive, they have no control,” said Jörg Jesse, the head of prisons for the region.

Less than 24 hours after he returned home, Semple found himself Googling his way through the brain science literature on young adults and crime. Since the 1990s, studies of MRI scans have shown that the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with planning and solving problems, keeps developing pathways to other parts of the brain, including those related to emotions and impulses, well into the second decade of life. This is usually the given explanation for why a disproportionate number of crimes are committed by young people, but Semple noticed that was also true in prison, where people under 26 were responsible for a quarter of all “reportable incidents,” despite being less than a fifth of the population.

Semple asked the Vera Institute of Justice, which organized the Germany trip, to help him develop a youth prison like Neustrelitz. He envisioned dedicating an entire facility, but budget issues forced him to scale it back to a pilot project. He picked the Cheshire Correctional Institution. As the staff discussed possibilities, Scott Erfe, the facility’s warden, noted that older prisoners tended to “adopt” younger ones and give them advice. At community events, he’d seen a lifer named John Pittman get kids to toss away their street scowls and open up about their vulnerabilities. He wanted Pittman to pick others like him to live with and mentor the young prisoners.

Pittman, a tall, soft-spoken man who has earned the nickname “Father Time,” is serving 60 years for the 1985 murder of his wife in Hartford. He won’t speak about the crime, saying only, “Some of us have taken lives, so it’s only fair that we try to save lives.” Semple was skeptical of the mentorship idea, since there is also a history of older prisoners preying on young ones, financially and sexually, and in Germany the rehabilitation programs were run by staff. But Erfe convinced him. (Such exploitation, so far as officials can tell, has not taken place in the TRUE unit.) As Erfe explained it, “Part of this is guards and counselors realizing they can’t speak to these young men with knowledge of what they’re really thinking; only older prisoners from the same neighborhoods can.”

And so the German model took on an American influence. “Sometimes you see what you need is in your backyard,” Pittman said.

Left-leaning supporters of prisoner rehabilitation tend to talk about the social and economic forces that lead to crime, while conservatives focus on personal responsibility and poor choices. These two approaches are not in conflict in the ethos of the TRUE program: a bad environment causes bad decisions, but it’s up to you to rise above it. “The violence and intermittent chaos of street life translates to prison life with ease,” the mentors wrote in an introductory note to the young men. “Perhaps there has been no consideration of how the movement from point to point has stripped you of your voice and made you feel powerless…This does not have to continue to be your reality.” The mentors turned the wing—an open floor, dotted with tables and surrounded by tiers of cells—into a temple of self-improvement. A day of work and study can last from 7:30 a.m. until 7:30 p.m. Chalkboards feature quotes attributed to Booker T. Washington and the Buddha.

They devised ways to keep everyone accountable. If officers see someone breaking a small rule—an untucked shirt, a radio left on, tardiness to a class—they can write it down, without the offending prisoner’s name, on a chalkboard, and then it’s up to his peers to figure out who broke the rule and ask him to fix the problem. When two young men have a dispute, they sit with others in a circle and discuss what transpired and how to resolve the problem; it doesn’t escalate towards violence and harsh disciplinary tactics such as solitary confinement. Punishments can include doing push-ups and learning dictionary words. There is an emphasis on practical life skills; they get mock currency, and they pay mock rent and taxes. They can get bonus pay for doing extra work, such as cleaning a common area, and fined for disruptive behavior.

But the main thrust of the programming is emotional growth, to get the men to analyze how their own anger and sadness alchemized into decisions that harmed others, and then to chart another path. There is a lot of talking. They talk about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In “Hip Hop Hermeneutics” class, they discuss lyrics as a way to explore the pressures they felt growing up. In the “Current Events” class, they view the news of the day through a personal lens. One popular subject was Aaron Hernandez, the New England Patriots football player convicted of murder who later committed suicide in a Massachusetts prison. Even as he achieved fame and fortune, they noted, Hernandez remained connected to friends in gangs. They spoke of trying to escape their pasts while feeling pressure from old friends to prove they are not “getting soft.”

“You go back out, seeing guys run, and you don’t run?” Davon Eldemire told the class one day last November. “The change is scary.”

When Eldemire first arrived in prison, he spent time mostly with men he knew from outside. When one was attacked, they banded together and fought back. “I was a tough guy, you couldn’t tell me nothing,” he said. In 2014, he received a disciplinary report for getting into a fist fight. But while working in a prison kitchen, he met an older prisoner who gave him memoirs by Martin Luther King Jr. and the boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. This man noticed that Eldemire talked a lot about Saniyah. “You say you love your daughter,” Eldemire recalls him saying. “But are you doing the right things?”

Back in his cell, Eldemire would find this challenge nagging at him: “On the streets nobody ever said, ‘Are you really living for your kids?’” He found himself growing bored as the friends who called always wanted to talk about the same petty schemes to make money, dealing drugs, chasing women, getting into fights.

Once in the program, he drew Pittman as his mentor, and they talked about his plans for when he gets out, his family relationships, his emotional responses to stress. “I think he’s really helped Davon see the value in being a father figure, how the way you live really affects those who look up to you,” said correctional officer James Vassar, who works in the unit. “And then he models that. He’s like the grandfather.” In essays, Eldemire reflected on his past. “Becoming a product of my environment had me chasing a dream that cannot manifest,” he wrote. “That dream was to sell drugs, promote violence without ending up in here.” He steeled himself to deal with teasing from prisoners who weren’t in the program. How’s that kindergarten going? they’d say.

It is unclear just how widespread such skepticism is among other prisoners, or whether it would imperil efforts to expand the program. Not all officers are sold on the idea, either. “Some told me there is a lack of structure” in the TRUE program, said Rudy Demiraj, president of AFSCME Local 387, a union representing officers. Giving the young men push-ups and dictionary words can seem like an insufficient deterrent for officers used to sending them to solitary confinement and revoking phone and commissary access. “We need to get back to holding people accountable for their own actions. It seems to us…that this program is not geared towards that,” he said. Demiraj would rather see such resources focused on prisoners with imminent release dates, and many in TRUE will be in prison for long stretches.

Demiraj said he’s open to being convinced by hard data that shows the program’s participants commit fewer crimes once they’re out, but such data could be years off. (Three years is a common timeframe for tracking new crimes.) In the meantime, Semple is hoping to expand—a comparable women’s unit is slated to open later this year. As the program grows, it will inevitably include young men who are not as committed as the first class. And myriad factors out of the department’s control affect whether someone commits a crime after leaving prison. “We know we won’t bat a thousand,” Semple said. “But there are also plenty of people with no history of incarceration, or even police interaction, who we read about on the front page. There is no magic wand.” He added that he instructed staff to pick prisoners who seemed like they needed help, not ones already committed to change. “If I wanted to impact recidivism, I would have picked cupcakes,” he said.

If the Connecticut story is a lesson in how criminal justice experiments happen these days, it is also a lesson in their limits. Of the nine men released from the TRUE program, one is back in prison after a technical parole violation. That is not officially a new criminal charge, but there is no telling how the public would respond if someone released from the program committed a serious crime. Even now, one state senator is pushing to restrict a different program that allows prisoners to earn early release through good behavior, citing one man released early who shot a police officer.

The TRUE program was cultivated with the express support of Democratic Gov. Dannel Malloy, who joined Semple for a day on the Germany trip and has also pushed a legislative initiative called the “Second Chance Society,” which includes reduced penalties for drug possession and an easier route to parole. But he is not seeking another term this November, and in a 2016 Quinnipiac University poll, 44 percent of Connecticut voters said they disapproved of how the governor was handling crime; only 40 percent approved. His predecessor, Republican Jodi Rell, vetoed efforts to shorten prison sentences while supporting “three strikes” laws. The TRUE program has not come up in the current race, which still features a wide-open field, but the next governor could easily replace Semple. Of the four department heads on his tour of Germany in 2015, he is the only one still in his position. It is impossible to tell whether the TRUE program would survive a change at the top.

And even if the next governor likes the idea of TRUE on paper, budgetary constraints may keep it small. The current program cost $500,000 to set up, much of it coming from federal grants. A lot of that cost was for the initial training and overtime, but the necessity of having more staff than usual around may inhibit the project’s growth. Semple said a typical housing unit would have two officers during a day shift, but in TRUE there are four, which is more in line with how the department would staff a mental health or solitary confinement wing.

But if TRUE doesn’t grow or prove itself through data, Semple sees the program as worthwhile for how it has already cultivated a prison environment more like the one he saw in Germany. “We’ve taken a more dignified approach,” he said. That’s also the perspective of Alex Frank of the Vera Institute of Justice in New York, who has been commuting regularly to Cheshire to develop the program. She sees it as part of a larger movement in prisons that will survive, no matter what happens to this particular experiment. “The starting point is not, ‘Everyone is messed up.’ The starting point is, ‘Everyone has potential,'” she said. “We make this accessible to everyone, and if it doesn’t work, it’s on the system—hold the mirror up.”

On a January evening, Eldemire rushed out of the TRUE unit wing to the visitation room at the front of the prison, where his sister Leona and mother Linda were waiting with Saniyah, who is now six. Her hair was laced with red and white beads, which clacked together as her father scooped her up. She picked at his beard as he asked her to spell new words and inquired about her classes at school. Over the next hour, any time he’d put her down for a few moments, she’d look up at him and say, “Upsies! Upsies!” John Pittman snapped a family picture.

Davon’s sister Leona had never felt the need to see her brother since she could talk to him on the phone, but once she learned he was making an effort, she realized she needed to make one, too. One night, their mother Linda’s usual ride to the prison fell through. Leona said she was too tired to drive her. She laid down to rest. “Something is weighing heavy on my heart,” she recalled. “He’s going to see all those families, hugging and kissing their loved ones, and he’ll be alone…He’s going to think, ‘What am I doing this for?’” She drove 90 mph to get her mother and made it to the prison 15 minutes after the visiting time had begun.

“He knew all these big words all of a sudden,” she said. He was interested in learning real estate and flipping houses when he got out. He talked about investing money. When she brought up new clothes and shoes she liked, which used to be a frequent topic of discussion between them, he said, “You don’t need all that! Tear up that credit card!”

During regular visitation hours, visitors and prisoners sit across a table from another and are allowed only limited physical contact, but in the “family engagement” sessions of the TRUE program, the rules are relaxed, and the interactions look a lot like they do in Europe. They are allowed to sit next to their visitors and hold their kids. Counselors from the program call family members regularly to update them on their loved one’s progress. If they can’t find family who seems interested, they look for other people who can visit and keep the young man accountable, whether an old coach or a just a close friend. A 2011 Minnesota Department of Corrections study found that prisoners who regularly received visits were 13 percent less likely to be convicted of a new felony in their first five years of release. Often, Pittman has found that when he pushes young prisoners to explain bad behavior, they will say they are having trouble getting in touch with their families.

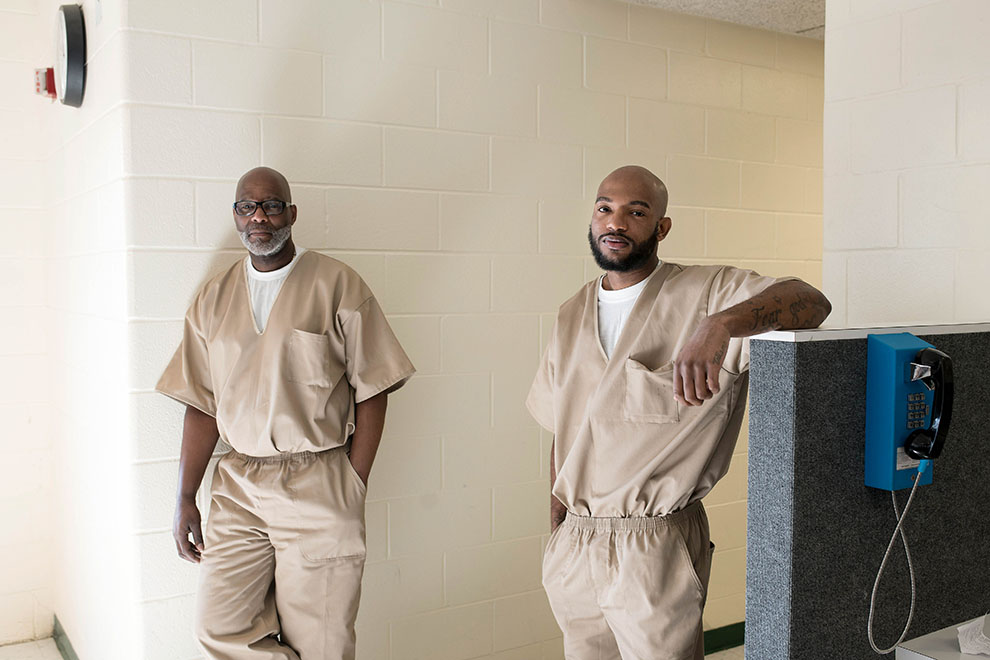

John Pittman, left, and Davon Eldemire at Cheshire Correctional Institution.

Karsten Moran / The Marshall Project

The TRUE mentors and department staff are working with two nonprofits, Workforce Alliance and COMPASS Youth Collaborative, to set up the mentees with jobs and support services such as counseling and education once they’re out. Those who have been released call the staff with updates on their progress, and there is talk of creating a “TRUE Alumni network.” But all this is in its infancy since so few men have been released.

Davon will be up for parole in three years, and it remains to be seen whether involvement in the TRUE program will help prisoners like him when they go before the parole board. His sentence officially ends in 2027. Until then, Leona dreads the moment when Saniyah comes to understand that her father is in prison; for now, she just thinks he’s in a “special school.” “She’ll say, ‘Why did you guys lie to me?,’” said Leona. “I’ll say, ‘It was to protect your heart.’”

When it was time to leave, Saniyah gripped her father tight. “I love you so much,” she said.

“Be a good girl, okay?” he said.

Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.