<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/norue/13938341399/in/photolist-fGLah-neFDi2-kaaoyN-83Rm1d-7ofhPW-fxSF7k-cCS9zN-cCScMQ-7Fwt7x-cCSbfj-aNPhJ-gF3nXV-7g6rLq-wC8JX-do7WhD-fxStP6-38wBWq-aEukcY-cEdovs-pWMCX5-572Gk-K3z4v-5zCkcN-76wKPQ-LYwY7-a91URN-agcKi3-8TaAdQ-8ad6YY-rpJN4-62R4Ev-6qoBmK-aekaK4-de3U-9icSX1-6qsN9C-dLFf89-5NrRia-7h76DU-kBxd2-gxTYR-gjmKrq-8Aus3-bjoHVX-5jJ1TB-6AVJ7p-kxZy8-byTHXc-8AvSm-7DMweA">AndreasS</a>/Flickr

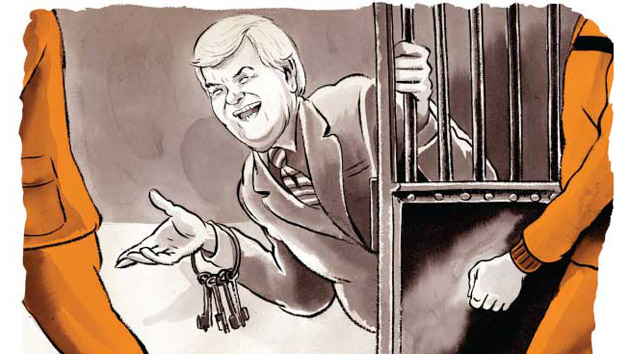

California’s three-strikes law used to mean that all third-time felons had to spend at least 25 years behind bars—pretty harsh, considering that the third strike could be the result of stealing a $2.50 pair of tube socks. Last year, voters decided to scale back the policy, and passed two initiatives to give judges more sentencing discretion and retroactively reduce the penalties for low-level drug and theft crimes. Law enforcement leaders warned that the reform would set free “thousands of dangerous inmates,” and called it “a radical package of ill-conceived policies” that “will endanger Californians.”

But almost five months after the second initiative passed, that warning sounds increasingly overblown. About 45 percent of inmates released from California prisons normally re-offend within 18 months. Of roughly 2,000 former life prisoners freed as a result of the three-strikes reform, only 4.7 percent have returned to prison, according to the New York Times. These ex-convicts had been out for an average of 18 months.

Experts say that intense exit counseling helped contribute to the low recidivism rate. “There’s a lot of emotional work,” Mark Faucette, director of community relations for the Amity Foundation, told the Times. “They’re moving from a number to a name.”

Two decades ago, fear of crime was at a nationwide peak. The murder of 12-year-old Polly Klaas by a career criminal helped push Californians to pass the three-strikes law, the country’s strictest, in 1994. Crime rates did fall—but a 2012 study from UC-Riverside later found that it had nothing to do with three strikes. The law also added an estimated $19 billion to the state prison budget. As federal courts started pressuring California to shrink its prison population in 2009 due to inhumane treatment and overcrowding, the three-strikes legislation made even less sense.

The tides may be shifting for the rest of the country, too. As my colleague Shane Bauer writes, a 2013 poll found that even among Texas Republicans, 81 percent favor treatment over incarceration for drug offenders. Other states—more than 20 of which also passed three-strikes laws in the 1990s—may also soon be questioning prison time as a blanket solution for low-level crimes.