![]()

In 2007, Donald Bogardus contracted HIV from his long-term partner. When he later had unprotected sex with a man who didn’t know Bogardus was HIV positive, he was charged under an Iowa law that criminalizes the transmission of HIV.

“I wanted to tell him,” Bogardus told the Daily Iowan, “but when I went to say it, I clammed up…I was afraid he was going to blab it out to everybody.”

Now Bogardus—a church-going, nursing-home worker with cerebral palsy and a pet goldfish named Survivor—faces 25 years in prison and lifelong sex offender status. For many opponents of criminal HIV transmission statutes, who argue that they are ineffective at preventing transmission and stigmatize the HIV-positive, he’s become the poster boy for the laws’ severity.

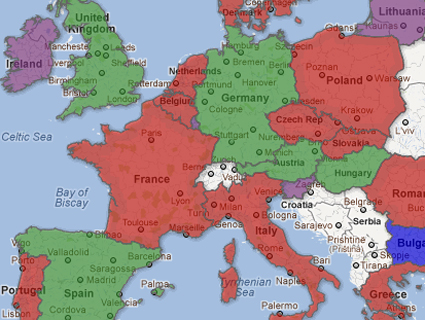

According to the Center for HIV Law and Policy, 32 states and two US territories have some sort of HIV-specific criminal transmission statute. Forty-five states have laws against HIV-positive people not disclosing their status during sex, acts of prostitution, needle exchanges, or when making organ, blood, or semen donations, or have prosecuted people for these behaviors under general felony laws. In 13 of those states, there are laws against HIV-positive people spitting on or biting someone, neither of which has ever been proven to transmit HIV.

Twenty-one states have used general felony laws to prosecute HIV transmission, rather than statutes specifically criminalizing transmission. Beirne Roose-Snyder, managing attorney with the Center for HIV Law and Policy, argues that the common name for the statutes—criminal transmission laws—is inaccurate since none requires that transmission of HIV actually occur. Instead, the laws usually punish failure to disclose HIV-positive status to a sexual partner as intent to do bodily harm.

While comprehensive charging data is hard to come by, Roose-Snyder believes that over 400 HIV-positive people have been prosecuted with criminal transmission since 1990; a 2010 report from the center put the number at 350.

Iowa’s 1998 criminal transmission law is one of the harshest in the country. Failing to disclose a HIV-positive status can bring a 25-year prison sentence and lifelong sex offender status. According to statistics from the Iowa Division of Criminal and Juvenile Justice Planning, 37 charges were brought under the law between 1999 and June 30, 2011. While 25 of the prosecutions were successful, only 15 people were convicted, since several people were targeted for more than one alleged violation.

Iowa’s law does not require that the sexual partner at risk of transmission actually contract the virus, and prosecutors have even won cases where a condom was used.

That’s what happened to Nick Rhoades. Though he and Adam Plendl used a condom when they had sex, and Plendl didn’t contract HIV, Rhoades was arrested and charged with criminal transmission of HIV. He plead guilty on the advice of his lawyer and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. On Thursday, Rhoades’ new lawyers appealed to the Iowa Supreme Court arguing that the conviction should be overturned because he had used a condom. “The law only applies to those who intend to expose others to HIV,” said Christopher Clark, an attorney for the LGBT rights group Lambda Legal, Rhoades’ new legal representation, in a statement posted on the organization’s website.

Most of these state laws originated after the federal Ryan White Care Act of 1990. The law funded local and state HIV treatment and prevention programs, but only if states criminalized the intentional transmission of HIV. Many state laws created in response went further than the federal law required and defined “intentional transmission” as including not disclosing HIV-positive status to a sexual partner. In 2000, the act was reauthorized without the criminalization requirement, but state laws persist.

Though Roose-Snyder of the Center for HIV Law and Policy believes that the number of prosecutions under these statutes is increasing, there has also been a push to amend the nondisclosure laws. The Obama administration’s 2010 AIDS initiative argued that the laws “may make people less willing to disclose their status by making people feel at even greater risk of discrimination.” In September 2011, California Rep. Barbara Lee introduced the REPEAL Act, which would encourage states to repeal their criminalization laws. The bill argues that intentional transmission is rare; that criminalizing transmission “undermines the public health message that all people should practice behaviors that protect themselves and their partners from HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases”; and that the life expectancy of people with HIV has increased in the years since most of the laws were passed, so their severity does not reflect medical advances.

There has also been movement to modify the laws at the state level. A revised bill passed an Iowa Senate subcommittee in February and would treat transmission of HIV as a misdemeanor like hepatitis and tuberculosis. And most recently, in May both houses of the Illinois Legislature passed an amendment to their state’s criminal transmission law that would exempt condom users. Gov. Pat Quinn is expected to sign it into law.

While opponents of criminal transmission laws in Illinois hail the bill as an improvement, they are critical of a provision that would amend the state’s law and allow courts access to HIV test results to prosecute criminal transmission. The fear, legal advocate Owen Daniel-McCarter told the Chicago Phoenix, is that “[These new enforcement measures] may dissuade someone from getting tested because then there is no way to prove a crime.”