FBI/Zumapress.com

Read Karen Greenberg’s previous coverage of the Ghailani trial here, here, and here.

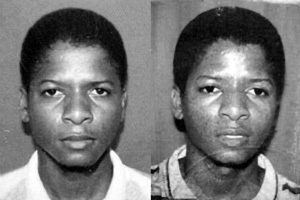

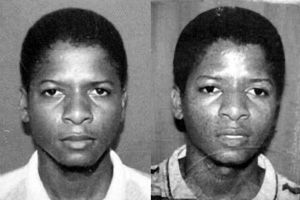

Just after 2 p.m. EDT yesterday, October 12, it finally happened. The courtroom was full of observers, press, and witnesses. The defendant, Ahmad Ghailani, wearing a light gray sweater and a matching gray plaid tie, warmly greeted both his current attorneys and the team that worked on his behalf at Guantanamo. He seemed to feel he was among friends—a stark contrast to the sentencing two weeks ago of Aafia Siddiqui, the neuroscientist and accused terrorist convicted of attempting to murder her interrogators, who bitterly disavowed her lawyers in open court.

Judge Kaplan began the Ghailani proceedings, asking the freshly sworn-in jury of 12 members and 6 alternates to stand, raise their hands, and swear to faithfully perform their duties. And before you knew it, after months of pre-trial hearings and whispers that this case might never find its way to court, opening statements were in process. US Attorney Nicholas Lewin, low-key, direct and to the point, squared off against defense attorney Steve Zissou, who was discursive, slightly more emotional, and seemingly confident of his client’s innocence.

The lines of argument set out the two narratives that will shape this trial. The first will be that of the government. Their plan seemingly has two prongs: to put Al Qaeda on trial, connecting Ghailani with the rhetoric and aims of the organization as a whole, and to convict Ghailani not just of the Dar es Salaam bombing, which killed 11 individuals, but of the simultaneous bombing in Nairobi, Kenya, which resulted in the deaths of more than 200 individuals. All told, he is charged with 224 counts of murder.

The first witness was a survivor of those bombings—John Lange, the former charge d’affaires at the US Embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. He matter-of-factly described the day of the bombing—the meeting he attended with a group of development experts, the explosion, the falling chunks of plate glass, a dying man’s charred body. The prosecution showed photos of the building, carefully pointing out spots of blood. Still, I couldn’t escape the sense that compared to many New Yorkers’ memories of 9/11—the thousands of victims, the overwhelming horror and devastation—this story must have felt almost anti-climactic. Ghailani’s trial is the most prominent terrorism trial of the 9/11 years, a kind of stand-in for the prosecution of accused al Qaeda figure Khalid Sheikh Mohammed; yet the attack he’s actually being tried for is far removed from 9/11 in time, place, and scope.

Ghailani’s case was chosen as the first of the Guantanamo high-value detainees to be tried in federal court in part because the government knows how to try this case: Others implicated in the bombings have been convicted in federal court. But the plain fact is that 9/11 shifted the ground under our feet. Time will tell whether this shift—the measure by which we assess the scale of a terrorist attack—will affect the jury. But what is clear after the first day of proceedings is that trying the Embassy bombings cases anew, post-9/11, will be anything but déjà vu.