In August 2018, a few weeks after he was shot eight times at a party in Oakland, Andre Reed was recovering at his mom’s house, his wounds still open, when he got a message on Instagram. It was an old friend from his school days. She said some people were looking for him and wanted to talk.

Reed, then 35, had recently been released from federal prison, after years of bouncing in and out of the criminal justice system. “Is this the police?” he asked. She said she didn’t think so but would check. “They don’t got nothing to do with the police, nothing like that,” he recalls her saying when she messaged him back.

Reed was being sought by outreach workers who wondered if he’d like to meet with a life coach to help him get his feet back on the ground. It was the latest version of a strategy to drive down gun violence in a city with one of the country’s highest murder rates. The program, called Operation Ceasefire, draws on data to identify people who are at the highest risk of shooting someone or being shot themselves. At a meeting with police and community members, known as a call-in, the recruits are told they’ll be punished if they keep engaging in violence. But they’re also offered access to housing, jobs, medical care, and life coaches, plus a monthly stipend if they accomplish goals like signing up for health insurance, opening a savings account, and staying in touch with probation officers. The idea is to try to prevent shootings not by flooding the streets with armed police, but by connecting people with resources and helping them build relationships.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

Reed seemed like a perfect candidate. For nearly his entire childhood, his dad had been in prison, and Reed himself had been in and out of juvenile detention since the seventh grade. And he’d already had run-ins with gun violence. That July, he’d gone to a barbecue outside an apartment building in West Oakland. As he polished off some Chinese food while catching up with friends, two men in black ski masks walked through the gate and opened fire, striking Reed’s legs. He collapsed beside a car, his thoughts on his 5-month-old daughter and 10-year-old son. The shooters fled and an ambulance arrived, rushing him to a nearby hospital, where he stayed for about a week. Now, back at his mom’s house in the suburbs, he struggled to move. He slept most of the day, groggy from painkillers, or watched movies. He worried he’d have no other option but to rejoin his crew on the streets once he healed.

The question of how to reach men like Reed, who are at high risk of committing or falling victim to violence, is pressing in cities like Oakland. Nationally, murder rates have fallen since their last peak in the 1990s and are now back to their 1965 levels. But the progress has been uneven. For Black men between the ages of 15 and 24 in the United States, homicide, mostly by gunfire, is still the leading cause of death by far, killing more of them than the next nine top causes of death combined. During the first few months of the pandemic, shootings crept up again in some cities, including Oakland.

Many politicians have long believed that to reduce violence, cities have to put more officers on the streets and make more arrests. President Donald Trump announced in July that he plans to send hundreds of federal officers to cities around the country, with a goal of ramping up prosecutions. Ceasefire flips that script: It calls for fewer arrests for nonviolent acts, an end to the scorched-earth tactics that fueled the drug war, and an emphasis on reaching the relatively small number of people involved in most shootings. In 2015, half of all gun homicides in the United States took place in just 127 cities and towns; more than a quarter were in neighborhoods representing only 1.5 percent of the total population, according to a 2017 report by the Guardian. An analysis of shootings in Oakland revealed that just 0.1 percent of the city’s population was responsible for most of its homicides. But many men at the highest risk of this violence—often members of gangs, with a history of shooting or being shot—are also the most isolated from social services, or the most resistant to them.

Dozens of cities have experimented with programs like Ceasefire in recent decades, starting with Boston in 1996. Yet the approach, which goes by various names, has had mixed results, partly because cities have rolled it out in vastly different ways. Some city leaders promise social services but spend more money on the policing aspect of the program: They lean on cops to track down men at risk of violence, threaten them with punishment, and arrest them if they don’t get in line.

When outreach workers in Oakland first got in touch with Reed, he knew Ceasefire had a reputation in the neighborhood—guys who slipped up again could find themselves in handcuffs. And going back to prison was the last thing he wanted. Plus, he was tired of case managers. He still had flashbacks to parole programs from years earlier, where he mostly watched movies and wasted time. “I always wanted to change, but all the programs just, you know, blowin’ smoke,” says Reed, who has long braids and tattoos of skeletons and smoke winding up his arms.

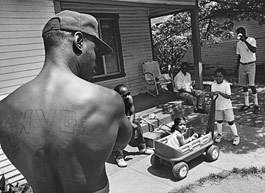

Andre Reed, 37, and his life coach, Len Haywood, at breakfast.

Preston Gannaway

Oakland’s residents have other reasons to be skeptical of a reform effort involving the police. The city’s cops have been under federal oversight for brutality and civil rights abuses for 17 years. And Oakland tried and failed to implement Ceasefire twice before, in 2007 and 2011. In 2013, at the behest of pastors and other residents, the city rolled out Ceasefire for a third time, but with a twist: The program would scale back its emphasis on law enforcement and focus, through life coaching, on helping participants develop positive relationships with mentors who grew up in similar neighborhoods as they had.

It’s working. Between 2011 and 2017, the number of shootings in Oakland dropped by more than 50 percent. Meanwhile, arrests have declined, and officers are solving more murders than they once did. Police departments in New York City, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Washington, DC, have sent officials to observe the city’s alternative model. “What Oakland’s doing is certainly the Ceasefire strategy, but it’s a very evolved version,” says Mike McLively, an attorney at the San Francisco–based Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. Life coaches, clergy, and victims’ family members all play important roles in reaching out to at-risk men. Oakland “paid much more attention to a strong community voice and to providing a more robust set of social services,” says researcher Thomas Abt, a Justice Department official during the Obama administration and author of the 2019 book Bleeding Out.

And now, amid nationwide protests to defund law enforcement and rethink how cities handle public safety, curiosity about Oakland’s strategy is growing. In Minneapolis, after protests over the killing of George Floyd sparked a debate about dismantling the police, some City Council members proposed funneling more money into a program like Oakland’s.

Reed was still skeptical of Ceasefire on the warm day in September 2018 when he, his mom, and his son drove two and a half hours from her house in suburban Oroville to Oakland to get more information on the mentorship program. Leaning on a cane, Reed limped from the car into an office building and rode the elevator to the third floor. At a conference table surrounded by a handful of life coaches, he sat quietly across from Leonard Haywood, a polite man about a decade his senior. Haywood offered to work one-on-one with him as a coach. Reed recalls, “I thought he was probably full of shit.”

At the end of the meeting, Reed didn’t make any promises. But when he went home again, the texts started coming. “Hey Dre, how you doing?” Haywood wrote shortly afterward. “Just wanted to check in, see how everything is going. Let me know if you need anything, if there’s anything we can do.” Haywood kept in touch with Reed for about two months, asking how the recovery was going. “I was totally surprised,” Reed recalls. The texts and calls made him wonder if Haywood actually cared. Reed said he’d consider working with him if he moved back to Oakland.

From the beginning, the call for Oakland’s police to rethink their approach to gun violence came from community members—and the odds were very much stacked against them. In 2003, Oakland was reeling from a murder crisis. The city had seen an 81 percent surge in homicides over the previous four years, to 113 killings in 2002. But Mayor Jerry Brown scoffed at a City Council member’s suggestion that offering better job training for people with criminal records could help prevent shootings. “Do you think if we put the Godfather and his gang in a job program, they’d change their line of work?” Brown told a reporter in 2002. He instead pushed to hire 100 more police officers, who could flood high-crime areas of East and West Oakland in search of drugs and guns.

Then the killings came to Barbara Lafitte-Oluwole’s doorstep. Lafitte-Oluwole, a community organizer originally from Louisiana, lived in a green and burgundy Victorian house in West Oakland. On June 14, 2003, her stepson, Tokumbo, was celebrating his 22nd birthday with friends outside a KFC when a man fired six bullets into him, killing him instantly. Detectives never caught the shooter. Lafitte-Oluwole believes her stepson was targeted because he was preparing to testify against men who allegedly killed his best friend months earlier after an argument about a missing Uzi.

Steeped in grief, Lafitte-Oluwole started learning about Boston’s Ceasefire program, which cut youth homicides in half before city officials lost momentum and abandoned the strategy in 2000. She began working with a group of activists from the nonprofit Oakland Community Organizations (now Faith in Action East Bay) who bombarded public safety meetings with demands that city officials try the strategy. Eventually, in 2007, Mayor Ron Dellums agreed. Under Ceasefire, police would summon men at risk of shootings to a call-in.

Or at least that was the theory. After police officers surrounded people’s houses with squad cars to drop off the “invitation” to the first call-in, only two men showed up. By the end of 2010, the first iteration of Ceasefire in Oakland was dead, having done little to quell the shootings. The next year, a 3-year-old was gunned down while walking with his family in East Oakland. Officials briefly relaunched Ceasefire, but it fizzled out. By then, Oakland had the third-highest murder rate of any midsize city in the country.

Not everyone was ready to give up. Ben McBride, a progressive pastor from San Francisco, had resigned from his church years earlier after watching his nondenominational congregation lose family members to gunfire. Hoping to better understand the violence, in 2008 he’d moved with his wife and three daughters to part of East Oakland known as “the kill zone.” His first night there, after tucking the girls in for bed, loud bangs erupted outside their home. He dropped to his knees and started to pray, terrified. It took minutes before he realized they were fireworks coming from a baseball stadium.

His older brother, Michael, also a pastor, met one of the architects of Boston’s Ceasefire program while studying divinity at Duke University, and became curious about the model. The McBrides had grown up with an acute awareness of the violence inflicted on Black people: Their great-uncle had been tied to a railroad track and killed by the Klan. Their dad, who met Martin Luther King Jr. as a boy, had been jailed for protesting during the civil rights movement. And in college, Michael says he was racially profiled by two white officers who pulled him over, groped him, and forced him to lie on the ground.

Despite their misgivings about the police, the McBrides knew Ceasefire had worked in Boston. So Michael encouraged other pastors to learn about the strategy, and invited clergy from Boston to come share lessons from their city’s success. In 2012, about 500 local religious leaders, activists, and residents piled into an Oakland church to show their support. “He was very prophetic,” Lafitte-Oluwole says of Michael, whom the Obama administration later tapped as an adviser for a council that made recommendations about how to deliver social services. The huge community turnout helped convince Mayor Jean Quan and the police chief to restart Ceasefire—this time with some bold new strategies.

Data would prove crucial. For years, the police, who helped identify the participants, believed that 10,000 people, disproportionately teens, drove homicides in Oakland, which is why previous violence-prevention programs funneled most social services to a large group of teens. During the earlier iterations of Ceasefire, officers targeted known group or gang members who were on probation or parole for weapon or violence-related offenses—a broad category. Now the city’s public safety director called in advisers from the California Partnership for Safe Communities, a newly formed nonprofit, to examine data gathered from a year and a half of shootings and figure out more specifically who was involved.

The results shook police and city leaders’ assumptions. Just 400 men were responsible for the majority of the city’s homicides, the researchers found, and their average age was 28 or 29. The discovery challenged a long-held belief that people age out of violence in their 20s. Most shooters were Black or Latino and members of a street group, a term used in Oakland instead of “gang,” and they had forged strong ties with friends in their crew. They were typically fighting not over drugs, as was commonly believed, but over personal beefs. Most had a history of prison or probation, and many had been involved in a previous shooting, as either a perpetrator or a target. Because the men were older, they’d had more time to rack up bad experiences with official agencies and the criminal justice system, whether through foster care or the courts.

With the new data, Ceasefire officials could target services to those people for whom intervention might stanch the most violence. Most cities don’t do this analysis, says David Muhammad, Oakland’s former chief probation officer and now an adviser for the California Partnership for Safe Communities. Every week, law enforcement and criminologists review each shooting that occurred over the past seven days, and refer the gunmen and victims to Ceasefire if they meet most of certain criteria: They’re between the ages of 18 and 35, have an extensive criminal justice history, are part of a street group, and have a family member or friend who has been shot recently. “Data changed the whole dynamic,” says Ben McBride, “because we knew we could reach around 250 individuals, versus this feeling that there’s 20,000 people running around terrorizing the city and being terrorized.”

After Ceasefire resumed in 2013, about 20 probationers and parolees went to the next call-in at a community center. The room was tense. Men from rival gangs eyed each other from their seats. Between them sat pastors, police, and mothers whose sons had been killed. Law enforcement officers hovered in the background. Muhammad, the technical adviser, watched skeptically as officers in tactical gear tried to convince the men that the city cared about them. He and others pushed the city to scale back the police presence at future call-ins.

Community members participate in a Night Walk in East Oakland on Friday, December 13, 2019.

Preston Gannaway

At a later meeting, one of the participants pointed out that the incentives to leave their groups still weren’t good enough: “When you all ask me to put that gun down, it’s not just the gun I’m putting down, but my ability to be safe, my ability to belong,” Ben McBride recalls a man in his late 20s saying. It got McBride thinking about how some men turned to guns because their schools, the police, or adults in their lives hadn’t protected them. The question city leaders needed to ask now wasn’t whether these men were ready to change. It was, McBride realized, “Were we ready to be in a deep relationship with them? Were we ready to commit resources to them? Were we ready to transform society in a way they could belong to it?”

If the answer was “yes,” he knew it would take investment—voters would need to pass a ballot measure to fund Ceasefire and social services for its participants. It was a tough ask, because investing in Ceasefire also meant investing in the police. And ahead of the 2014 election, the country was grappling with the police killings of Eric Garner and Michael Brown. “There was not a lot of goodwill” between law enforcement and Black people in Oakland, says McBride, who went to Ferguson, Missouri, to protest Brown’s killing. He says police officers there called him and his brother the n-word and other slurs; both of them were arrested. Passing the ballot measure “was a heavy lift,” he says, because “we are working with a partner—the police department—that is very flawed.”

But the McBrides tried to remind people that investing in Ceasefire could have results—homicides had already fallen by nearly a third over the prior year. With Lafitte-Oluwole, pastors, and other community members, they spoke with congregants, who then spread the word to neighbors. That November, Oakland voters overwhelmingly passed Measure Z, which would raise $277 million over a decade—60 percent of it for the police, the rest for violence prevention programs, including Ceasefire.

The spending on additional services had the potential to save the city money in the long run. It would cost less than $10,000 to put someone through life coaching, according to Muhammad. By contrast, he says, a single shooting injury can cost the city more than $1 million including medical, police, court, and prison costs. Often it’s more: A 2015 analysis by Mother Jones and researcher Ted Miller revealed that nationally, each gun death averages about $6 million in total costs. Collectively, these killings cost the United States more than $229 billion each year—upward of $700 per person. And access to social services can help drive down shootings. In his book Uneasy Peace, sociologist Patrick Sharkey examined crime in 264 cities between 1990 and 2012, and found that each additional nonprofit focused on crime and social outreach was associated with a nearly 1 percent drop in murder rates.

But throwing money or programs at a problem can only get you so far. “Part of what’s been deeply disturbing about the way violence prevention has and hasn’t played out in cities is that for a long time it’s essentially been an inside game,” driven from the top down by mayors, police chiefs, and others who might not have been personally affected, says scholar David Kennedy, an architect of the Boston model. “Communities are no longer putting up with that. Because the most powerful influencer of behavior is not the cops—it’s what you and your community and your mom and your best friends and your girlfriend think about what you’re doing.” Since so many shootings are about interpersonal conflicts, breaking the chain of violence can be like breaking the chain of viral transmission in a public health epidemic.

In 2013, as Oakland began its third attempt with the Ceasefire program, community members pushed to be more involved. City officials decided to let volunteers help police reach out to potential participants individually rather than summoning them to group call-ins. One study by the city found that 65 percent of potential participants in Oakland accepted services when a community member was present at the ask, compared with just 25 percent who did when only police reached out. Lafitte-Oluwole, a decade after her stepson was killed, volunteered to do outreach. “A lot of people carry all these burdens,” she says, “not knowing they can seek help.”

City officials also started to think differently about how they offered services to the program’s participants. Giving someone a phone number to call for job training wouldn’t cut it. Now, life coaches, some of whom came up through street groups themselves, would build relationships with the participants, an addition to the program other cities hadn’t tried. They’d sit down with the guys and see if they wanted help with any immediate needs, like avoiding threats from a rival gang or finding housing. But the coaches’ main goal would be to spend time with the participants and build trust, even with men who were still involved with a street group or didn’t want a job. “Just because you aren’t motivated in the beginning, it doesn’t mean we give up on you,” says Haywood, who has been working as a life coach for eight years. “It’s not just a Monday-through-Friday, job-related thing. It’s deeper than that.” The life coaches work with people even if they’re still involved with crime, and they don’t share any information with police.

In 2018, only 10 percent of the men who went through the Community & Youth Outreach coaching program, where Haywood works, were rearrested after one year. In contrast, nearly three-quarters of men in their early 20s with juvenile records in California end up arrested again within a few years of their release from detention. Fewer than 1 percent of the Ceasefire participants who did the coaching program were rearrested for shootings in 2018.

In late 2018, Andre Reed moved into his girlfriend’s house in a city near Oakland and started meeting up with Leonard Haywood, or Len, his new life coach. Haywood, 47, also grew up in Oakland with a single mom. As a kid, he straddled two worlds, taking classes at a private school and then coming back to his East Oakland neighborhood, where he’d ride his blue BMX bike, rap Too $hort and Richie Rich songs, and shoot hoops. Some of his friends sold crack, but beyond the occasional fight, he mostly stayed out of trouble. His football, track, and basketball coaches encouraged him to stay in school. “Sometimes you can’t see certain things in yourself,” Haywood says now, reflecting on his mentors. “Thinking I can only go so far.”

By the time Reed limped back to Haywood’s office on the third floor of a Bank of America building in East Oakland in 2018, he’d discarded the cane and, thanks to the regular phone calls, his skepticism about Haywood. Reed appreciated that Haywood hadn’t rushed him to come before he was ready. “It’s all about meeting people where they are,” Haywood says of his approach.

At least three times a week, Reed and Haywood met at the office, Reed’s house, or out somewhere to eat burgers or burritos. Both are fathers, with boys about the same age, and they bonded over their Oakland childhoods and years playing football. Haywood told Reed about the night he spent in jail before dropping out of college. Everything about the experience—getting fingerprinted and thrown into a cell, being ordered to pull down his pants and bend and cough—felt like a violation. Reed found Haywood’s honesty refreshing. “Some people will talk to you but lie to you at the same time,” Reed says. “He told me the truth of everything, keeping it real with me.”

Andre Reed (right) and his life coach Len Haywood after breakfast in San Leandro.

Preston Gannaway

Haywood coaxed Reed into naming some of his goals. Safety was one. And he wanted a steady job to support his kids. Haywood referred him to SAS Automotive in nearby Newark, where he applied to build dashboards for Tesla cars. Along with his paycheck, he would receive about $200 from the city as a monthly stipend for staying employed and meeting with his parole officer. The job left less time to swing by the life-coaching office, so Haywood sometimes drove out to see him at the auto factory. Reed eventually moved to East Oakland, where he stayed in a duplex with his aunt just a few blocks from Haywood’s home.

“I think I text him ‘big bro’ first,” Reed says. “‘Big bro, do I need to come do something?’ That’s when he text back ‘little bro,’ and ever since then it’s just ‘big bro, little bro.’” If there was a shooting in Oakland, Haywood would reach out to make sure Reed was okay. He texted often: How was work, what you getting into today, you ate? Reed knew he could call his coach anytime. It was nice, he thought. The only other person who reached out regularly to hear how he was doing was his mom.

A few months after Reed started working at the auto factory, he invited Haywood into his living room, where he showed off the pile of gifts he’d stashed beneath a Christmas tree: PlayStation games for his son, and Barbies and cooking toys for his daughter, all purchased with his own paycheck.

On a Friday night last December around 7 p.m., Rev. Damita Davis-Howard spotted two figures heading down a street near her Baptist church in East Oakland. “Hey, young men. How you all doin’ tonight?” she called out to them as they passed a beat-up Chevy. “You be safe out here, okay?”

They both smiled. “You too,” one said, before turning to walk away.

Most Friday nights for seven years, Davis-Howard, co-director of Ceasefire, and other activists have banded together for organized walks through areas of Oakland at high risk of gun violence. Her brother was shot and killed when she was in her late 20s. Two of her second cousins were shot too, and her niece was shot on her way to a party. In 2018, four bullets hit her son while he was at a store, though he survived. Joining the Night Walks, she told me, makes her feel like maybe she can change things.

About 20 people dressed in white coats carried signs that read “Love One Another” and “Honk for Peace” as they marched past houses decorated with holiday lights along 85th Avenue. Two men waved and filmed the walkers on their phones as drivers honked in support.

“It’s like counting the apples in a seed,” B.K. Woodson, a pastor, had told the marchers at a gathering at Davis-Howard’s church before the walk. “We don’t know the effect that walking tonight will have. What we do know is that people see us, and they know us.” The city’s police chief at the time, Anne Kirkpatrick, joined the group for a prayer and clasped hands with some of the marchers. “I ask for forgiveness for what we as police have done to cause harm,” she said.

The Night Walks are the public face of Ceasefire, a way for pastors and other organizers to shore up support for the program in neighborhoods where many people are reluctant to work with police. But building trust can’t just fall on community volunteers. Police have to clean up their act too.

After decades of widespread sweeps for drugs and guns in Black and Brown neighborhoods, the Oakland police department scaled back arrests by 55 percent between 2006 and 2015. Ceasefire officers now say their goal is not to dismantle gangs, but instead to stop gang violence, targeting behaviors as opposed to groups of people. They still arrest men who commit violence. But after they do, supervisors with the program are often required to debrief the neighbors and leave a phone number. Those debriefings are “a great idea,” says Cat Brooks, co-founder of the Anti Police-Terror Project, a local group that supports families affected by police violence. “Communities should know why there was a major action on their street, because that is just as triggering as intercommunal violence is for us.”

The relationship between the police and the community remains fraught. By 2016, Oakland was on track for a record-low number of homicides. The Obama administration commended its police department as an example for other cities to follow. Then, as the city was hoping to end federal oversight, at least 14 Oakland officers were found to have repeatedly had sex with a 17-year-old girl, trafficking her between them. The police chief resigned, and criminal charges were filed.

After the scandal, Ben McBride and other community members debated walking away from Ceasefire because they could no longer trust the police. The city suspended the strategy. “I can tell you that the individuals on our team were embarrassed by it, wanted to throw in the towel,” says Captain Ersie Joyner, who then led the police department’s Ceasefire unit, and who says he also felt disappointed by a lack of accountability in the department in the fallout from the revelations. In the end, most community partners stayed, and Ceasefire resumed a few months later. Oakland closed the year with an overall drop in homicides. Seventy-two people were killed in 2017, the fewest since 1999. “We were able to pull it together and save people’s lives,” Joyner says.

There was more evidence that Ceasefire was working. In 2018, criminologist Anthony Braga and other researchers released a study showing that shootings in Oakland had dropped in half since 2011. Ceasefire was found to be directly associated with a 32 percent reduction in gun homicides, even after controlling for other factors like gentrification and seasonal patterns. This huge reduction, the researchers found, was distinct from homicide trends in other California cities.

It was cause for celebration, for a while. Then the coronavirus struck, and protests against police violence. Both would cast uncertainty over the future of Ceasefire and policing in general.

In late May and early June, thousands of people, including the McBrides and Cat Brooks, flooded Oakland’s streets to protest police killings of Black men and women. Some protesters demanded that Oakland slash $150 million from its police department budget; some insisted on dismantling the department entirely. “Whose streets?” Brooks shouted into a microphone at a protest in Downtown Oakland that defied the city’s 8 p.m. curfew. “Our streets!” hundreds of people around her replied.

At first glance, demands to defund the police department seem to threaten Ceasefire’s existence, given that it operates as a partnership between the community and the police. But even if cities slash funds for cops and recruit social workers to respond to noncriminal 911 calls, communities will still need to deal with deadly crimes like shootings. It’s possible, even likely, that the movement to reimagine public safety in America will create more of an appetite for strategies like Oakland’s Ceasefire. The McBrides, who are now calling on police departments across the country to slash their budgets, see Ceasefire as an avenue to defund traditional law enforcement and invest in communities.

Police in other cities are taking note. “They determined you can’t arrest your way out of a problem. That’s something we really took away,” says Andrew Shearer, Portland’s assistant chief, who visited Oakland to learn about the strategy. Milwaukee’s police chief, who visited before assuming his new role, has instructed his department to copy Oakland’s weekly shooting reviews.

In June, after Minneapolis City Council members announced their intention to dismantle their police department, they suggested they might invest more money in a local program that resembles Oakland’s. “That’s the kind of work we have to get behind,” Council member Phillipe Cunningham said of his city’s Group Violence Intervention strategy. “Because the more we can do that’s community-based, the less law enforcement that we actually need.”

That’s not to say Oakland has everything figured out. In 2016, researchers found that its officers were four times likelier to search Black men than white men during traffic stops. Another study showed that its police made arrests in 80 percent of homicides with white victims, but only 40 percent with Black victims, a pattern that exists nationally. Ben McBride says the city hasn’t been transparent enough about which men are targeted by Ceasefire. And Brooks, of the Anti Police-Terror Project, worries the strategy still leans too heavily on law enforcement. Participants have told her they believe they’ll go to jail if they don’t accept the program’s services. “When you talk to some of the brothers,” she says, “their message has been pretty clear: that if they don’t play, the cops are going to make life so uncomfortable they have no choice but to play.” Technical advisers for the city say the police don’t arrest men for rejecting services—just for engaging in violence. “For the purpose of keeping people in our communities who we love alive, we’ll continue to work with the police, but we’re still a far stone’s throw away from trust,” says Ben McBride, who eventually wants to see the current system of policing abolished. “What we’ve told them is, how do we come back and sit at a table with you all when you all are shooting tear gas and rubber bullets at us?”

The McBrides are asking the city to shift much more money away from policing toward the social services that keep Ceasefire humming. For years, the two brothers have also pushed Oakland to pay the volunteers who work on the program. The city recently reached an agreement with a community-based organization to provide stipends. “If you can find the money to pay police officers up to $300,000 a year to patrol the streets with guns, why can’t we find the resources to stipend community members to take time away to also reduce violence?” Ben McBride says. “We want to continue to see the kind of partnership and respect for people of color that are doing the work.”

“The work of saving lives, particularly Black, Latino, and Brown lives in urban America, is largely seen as the responsibility of Black and Brown people to do by ourselves—that was a problem here in Oakland,” Michael McBride said in March at a community meeting at the Allen Temple Baptist Church, the same place where he had rallied support for Ceasefire eight years ago. Men and women in the pews murmured in agreement. But saving these lives, he said, would require the city to spend more money on members of the community it had long neglected, and would require activists to hold their noses and work with the police. “We may not like each other, including the police—we’ll be honest, we don’t like you,” McBride continued. “But we have to work together. It’s important to keep reminding ourselves that collaboration is the silver bullet.”

Reed graduated from the life-coaching program last November, after about a year of working at the auto factory. When I met him during his lunch break one day in December, he talked about training newer employees and working toward a promotion. He and his girlfriend had a baby boy on the way, due in January. “I look in the mirror every morning and be like, ‘I’m proud of you,’” he said.

But the pandemic threw a wrench in his career plans. Shelter-in-place orders closed the production line and left him without work. When I tried to check in with him in March, he didn’t answer the phone or return my calls. Haywood told me he couldn’t reach him either.

Shootings, meanwhile, were creeping up in Oakland and other cities like Chicago and Baltimore. Maybe it was because of the warmer weather, or the fact that people were unemployed and stuck at home. Oakland had entered March on track to hit a record-low number of annual homicides, but by summer that goal seemed unlikely, according to Muhammad, though homicides were still half their pre-Ceasefire levels. Haywood wondered if the pandemic was to blame for the rising violence. He kept in touch with his clients by Zoom and FaceTime, and sent them care packages with wipes, hand sanitizer, and masks. But it was harder to build a connection virtually. Community organizers paused their Night Walks to maintain social distancing.

Reed and I eventually reconnected after I tracked him down on Facebook. I wondered if he worried about finding a new job in the middle of a recession, with a criminal record. But he said he was motivated to look for something better. Though his life coaching was technically over, Haywood had called just a couple of hours earlier, with phone numbers of contacts who might be hiring. Reed got to work filling out applications. “It felt good” to talk again to Haywood, Reed told me, “because he’s there for me.”

For a while, Reed was trying to convince his younger brother, who got out of prison late last year, to seek out a life coach too. “He’s still thinking about it,” Reed says. Almost every day, Reed texts his brother to check in. How you doing, what are you up to? “He want to do the same, but he want to do it on his time,” Reed says. “So I just wait. I just tell him, ‘When you ready, you just let me know. We can go from there.’”

The print edition of this article misidentified Thomas Abt’s previous role at the Justice Department. The story has been updated.