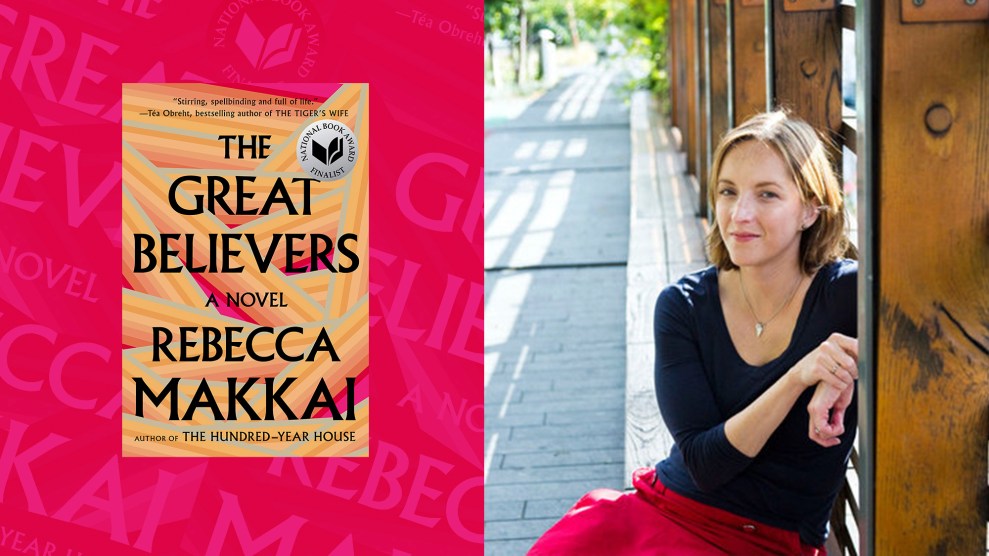

Mother Jones illustration; Philippe Matsas

Several of my colleagues have spent the past few weeks writing what we’re calling “Plague Comforts,” sharing what they’re doing to get them through this very weird moment. Some have been sweet and very personal. Others, a little more off the wall. I’ll admit that mine is a bit darker, but comforting all the same: I read novels that push me to think about, and hopefully understand, incredible loss.

I recently read a novel called The Great Believers from Rebecca Makkai. In focusing on a community of friends and their loved ones who survived the AIDS epidemic, it’s about the ghosts living among us—the people we’ve lost, and what we do with their legacies.

The book was interesting for me because, as a young queer person, I think a lot about the generation of LGBT elders that was lost in the 1980s. They were coming out of a moment of political and sexual revolution, and then they were gone. What genius was lost? What families never got a chance to begin? How do you make a world that’s long gone fit into what you have left? I posed these questions to Makkai on a recent episode of the Mother Jones Podcast, where we examine how literature has long been a space to make sense of grief in unfathomable moments. Here’s an edited version of that conversation below. And, of course, I recommend you listen to the full thing.

So let’s start with the idea for your novel, The Great Believers. When did you decide that you wanted to write about the beginnings of the AIDS crisis?

What’s funny is I don’t think I ever decided that. The novel evolved through plot from other directions. There’s a character in the book named Nora, who in the final version is really a minor character, who’d been an artist’s model in Paris in the 1920s. I set out to write a book about her. The AIDS epidemic in the ’80s was just mathematically where the end of her life was going to be.

I was seeing some parallels between what I saw as two different lost generations. I felt like maybe the AIDS epidemic, which is something I’ve always been interested in and interested in writing about, would be a subplot. And even before I started to write, it flipped.

Talk a little bit about what you mean by lost generations.

The title of the book, The Great Believers, is from an F. Scott Fitzgerald quotation that I just happened across when I was researching the art world in Paris in the teens and ’20s. He’s talking about his generation before the Great War.

I thought that was so odd, saying “we were the great believers,” when that’s the generation we think of as so jaded and debauched. It was those years of trench warfare. A generation of particularly young, able-bodied men were lost to the war and then to the influenza of 1918. It’s in the aftermath of that that Gertrude Stein says to Hemingway, “You’re all a lost generation.” That flip[ped] from “great believers” to “lost generation.”

I was already thinking about the parallels with a city like Chicago [in] the ’80s, where young gay men were coming from all over the Midwest, even from the South, to a place where they can co-exist, where they can form societies within society. And then those are decimated.

You did extensive research for this novel. Who did you talk to when you were trying to rebuild these communities in Chicago?

In a few ways, I’m writing close to home. I’ve lived in Chicago my whole life. But in so many ways, I was writing across difference. And that’s a terrifying thing to do. You have to approach that with a healthy sense of terror, I think. The absolute first step is to approach the people who can correct your misconceptions, who can let you know what things were like.

I spoke to survivors, but also doctors, nurses, lawyers, activists, advocates, journalists, historians, art therapists, everyone I could talk to. Sometimes multiple times, for hours on end. I became very close with almost everyone that I spoke to. I wasn’t looking for characters because I didn’t need that and I didn’t want that. I wasn’t looking for plot. I was looking for texture and I was looking for realism. It was really interesting to see what happened when I started asking them unusual, specific questions about that time.

What were some of the unusual questions?

I was asking things like: Where exactly in the lounge was the fish tank? What color was the carpet? Because for some reason, I can’t believe this, the AIDS unit at Illinois Masonic in Chicago was carpeted.

Doctors who founded AIDS units in Chicago, they’ve certainly spoken on the record quite a lot. Those are not the questions that the Chicago Tribune is going to be asking them to commemorate the 30th anniversary of something. I was asking kind of bananas questions and that would get people into more personal memories, more visceral memories, more sensorial memories. And get them off their soundbites.

So a lot of people are trying to make connections between the AIDS epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic. Do you think it’s fair to do that?

I think it would be really unfair to either situation to equate things. What I think we all should remember how to do is compare and contrast—seeing similarities, seeing echoes, seeing divergences, figuring out why things are different, where they’re different.

I think it’s a really valid way to think epidemiologically, historically. It’s a really valid way to think in terms of sociology. What are the ways in both cases that a pandemic, an epidemic, is magnifying the fissures, the inequalities that are already there in society? That’s a really important point of connection between these two.

I think that all of those points of connection, all of those points of divergence, are absolutely valid. And no one’s going to fit that into a tweet. No one’s going to fit that into a talking head soundbite on CNN. People are going to end up saying, “There are a lot of parallels,” or “They’re completely different.” And in fact, doctoral dissertations need to be, and probably will be, written on, say, the diversion of citywide government response in a certain city to the ongoing AIDS pandemic and the COVID pandemic.

I want to talk a little bit about your focus on survivors of a plague. There’s a moment in the book that really stands out to me where a character is in an airport and wonders how they would explain wifi to someone who died in the ’80s. It’s such a powerful detail of how grief works. Why was it important for you to focus on survivors?

I didn’t originally plan to. As I said, I originally thought I was going to write about this old woman. It changed into, I want this to be about the ’80s, the AIDS epidemic. And she’s kind of just around. Even so, at that point, I thought it was going to be set entirely in the ’80s. It was going to be a story that took place in crisis, that it was a story about crisis.

I was about 100 pages of the way into the book, just setting it in 1985 and 1986. But meanwhile, I was having all of these conversations with, by definition, survivors. I was becoming so fascinated by the 30-year gap that we were addressing every time we sat down to talk. I was fascinated by the way memory worked. Or the way that survivor’s guilt works over the long haul. I found myself thinking so much about those elements that I realized I needed to work that into the book. So I introduced these much thinner, much smaller chapters that are set in 2015 that are very much about survival.

It allowed me to write a much more hopeful book rather than just leaving you there in the muck. I’m certainly not writing about a time when AIDS has been solved, but I’m writing about long haul survival. That’s something that I learned so much about just on a spiritual personal level from the people I talked to. I was writing this during the 2016 election, everything was falling apart then as it’s falling apart even further now. And these were the voices in my ears. These are my elders who I was learning from and learning about.

Having grown up in Chicago, what do you remember about the AIDS crisis there?

It was the thing that everyone was talking about. I became aware of the world as the world was becoming aware of AIDS. I think it’s a generational thing. I was born in ’78. If nothing else, you’re watching the Oscars as a wide eyed 10-year-old and the “in memoriam” reel and the actors’ long political speeches when they win.

People slightly older than me keep asking, how on earth did this come on your radar? And people around my age get it completely. This was everything when we were growing up. It was the thing—that and famine in Ethiopia. Those were the issues. And in some fundamental way, you form yourself around those.

Additional reporting by Molly Schwartz.