Joe Giddens/PA Wire URN:49102726 (Press Association via AP Images)

This piece was originally published by the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative news organization in Washington, D.C.

Sue Mullins is an outdoor person. She gardens and takes her dog for long walks. But after she moved to Larimer County, Colorado, which has high ozone levels, she started running out of breath. At age 70, she was diagnosed with asthma.

Now 83, she’s staring down the coronavirus with two risk factors: age and lung troubles. For safety’s sake, she said, “basically I’m under family house arrest.”

Extra caution is an especially smart move in communities like hers. Air pollution, research shows, lowers our ability to fight off infections. It worsens reactions to viruses in people with health challenges like asthma. And it could have a pernicious effect in a pandemic.

Academics at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Montreal who studied the 1918 influenza crisis found that U.S. cities burning more coal for electricity—a stand-in for pollution at a time with little air monitoring—had substantially more “excess” deaths than low-coal cities. Their 2018 analysis compared outcomes in 180 cities, with the top third for coal use decidedly worse off than the bottom third.

“It’s this hidden cost,” said co-author Joshua Lewis, an assistant economics professor at the University of Montreal.

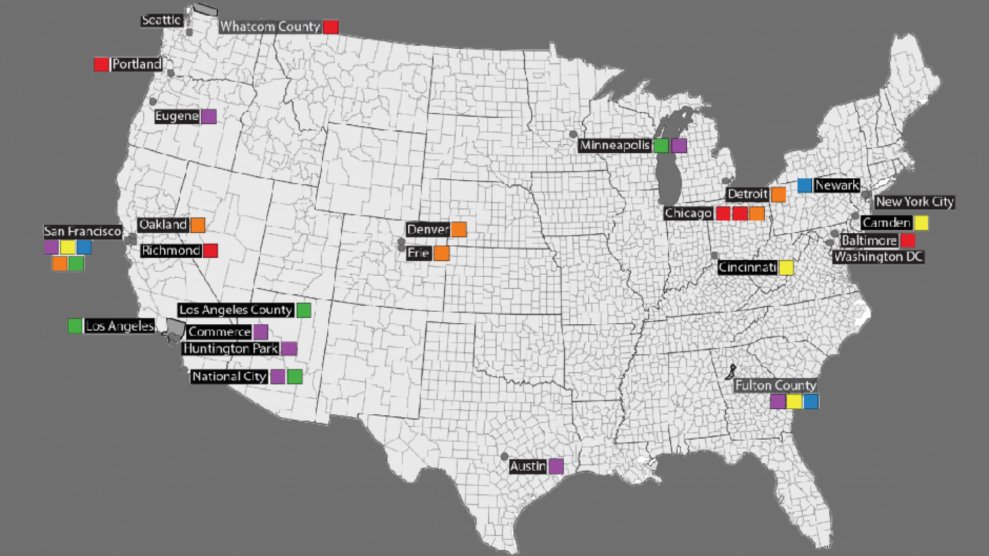

A century later, most of those higher-pollution cities are in areas in the top third of the U.S. for ozone, the damaging dust known as fine particles or both, a Center for Public Integrity analysis found. That includes New York, a city with a large outbreak of COVID-19, the disease the new coronavirus triggers.

The good news is that the cities choked with coal smoke in 1918 have far cleaner air now, by many measures. The bad news: Researchers keep finding health impacts from pollution at lower levels, and air-quality disparities mean some Americans—disproportionately people of color and residents with less income—breathe worse air than others.

“We see this unequal pattern across the United States,” said Jill Johnston, assistant professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California. “We know this kind of air pollution can really impact people across the life course, from babies to the elderly. It’s something that’s important when we think about health, to think about air quality.”

The rate of childhood asthma in New York’s Central Harlem has been estimated at four times the national level, for instance. As the coronavirus spreads through the city, Lubna Ahmed, director of environmental health for WE ACT, an environmental justice organization in Harlem, said she doesn’t want the “vulnerable communities that are so often forgotten” to get left behind yet again.

In Philadelphia, another city in the higher-pollution group in both 1918 and 2018, residents living near the East Coast’s largest oil refinery worked for years to get that major source of air emissions shut down. In June, a corroded pipe there ruptured, officials believe, triggering a fire and explosions. Refinery owner Philadelphia Energy Solutions filed for bankruptcy protection, and the complex was bought by a company that plans to redevelop it for other uses.

But Alexa Ross, campaign coordinator at the environmental justice organization Philly Thrive, is worried that the people—many African American—who breathed toxic emissions for decades in the low-income neighborhoods near the refinery are at greater risk from the new danger at their doorsteps.

“We know that our constituency does rank in that very vulnerable category of people that are immunocompromised and already have respiratory issues in particular, but also these other health struggles that weaken your immune system,” said Ross, whose group is mobilizing to help locals get the food and other necessities that they need.

Carol White, a Philly Thrive board member who has lived for 17 years in a home about 1,000 feet from the refinery complex, is helping get the word out to people, especially in nearby senior citizen high-rises. She’s facilitating by telephone and online from her house, where she’s staying put to keep safe: She’s 60 and was diagnosed with asthma last year after a refinery fire that preceded the explosion sent her to the hospital.

“Even just talking to you,” she said, “I have to catch my breath.”

People can’t undo past exposures. But there are signs air pollution is temporarily dropping in at least parts of the country amid a falloff in vehicle traffic as more Americans stay home. That’s different from the 1918 experience, said Karen Clay, a Carnegie Mellon University economics and public policy professor and lead author of the 2018 study about that pandemic.

Economic activity went down at that time, she said, but businesses “didn’t close if they didn’t absolutely have to.”

Clay and her co-authors looked at every city of more than 20,000 people with sufficient 1918 data in their 2018 paper. In a later study, they took a broader look at that flu, finding that heavy air pollution appeared to increase deaths up to 25 percent, and that poverty and poor overall community health also had substantial effects.

The Philadelphia refinery, seen in the distance from Philadelphia International Airport.

dclerch/Flickr

Too often, pollution, low income and poor health go together, a trap that people cannot escape. After her eldest daughter began to wheeze, Columba Sainz, Arizona field organizer for Moms Clean Air Force, an environmental health advocacy group, moved her family of five away from a Phoenix neighborhood where diesel buses idled. She worries about the residents who can’t afford to get out.

“People just stay inside the house or don’t spend much time outside,” she said.

Catherine Garcia Flowers, Texas field organizer for Moms Clean Air Force, wishes the country would treat pollution and climate change with the same sense of urgency as the coronavirus. As it is, the Houston resident said, too few people make the connection between air quality and health.

“People talk about allergies,” she said. “When I say, ‘Oh, what kind of allergies do you have,’ they often say, ‘I don’t know. I just can’t breathe.’”

Kern County, in California’s San Joaquin Valley, had the nation’s highest level of fine particles on an annual average and fifth-highest level of ozone in 2018. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency measured seven times the fine particles there as it did in Kauai County, Hawaii, which had the lowest levels of that pollutant among the roughly 550 counties with monitoring data that year. Kern’s poverty rate is more than double Kauai’s.

The entire San Joaquin Valley in central California, surrounded by mountains that hold in pollutants, has struggled with air pollution for a long time. Kevin D. Hamilton, co-director and co-founder of the Central California Asthma Collaborative, a nonprofit that provides asthma services in that area, said he keeps having to correct the assumption that bad air is only a problem for a relative few.

“Children, pregnant moms, folks that are working outside every day, … elders and people with compromised immune systems or chronic health conditions,” he said, listing off the groups considered more at risk. All are “very vulnerable to this pollution, and it’s causing their immune systems to be less responsive.”

Mullins, the Colorado resident, lived in Iowa for decades before moving back to her home state. From 1979 to 1989, she served in Iowa’s House of Representatives and saw firsthand the power constituents have when they speak up. She’s among the deluge of people who filed comments in 2018 opposing an EPA proposal to restrict its use of scientific studies in a way that would make it far harder to set stricter pollution rules.

A small barge travels down the Houston Ship Channel, with Shell’s Deer Park Refinery in the background.

Roy Luck / Flickr

The EPA, seeking comment now on a revamped version of that proposal, is still working to enact the change. That’s despite calls from the National Governors Association and other groups to extend comment deadlines because of the coronavirus, The Associated Press reported.

Mullins, who lives in Loveland, east of Rocky Mountain National Park and about 40 miles north of Denver, said it caught her off guard that a region so well-suited for getting outdoors has a problem with its air. Oil and gas development contributes. So does traffic. And then there’s climate change: Rampant wildfires in recent years have wafted pollutants to the Front Range.

Mullins takes seriously her children’s insistence that she stay inside, but she does still need to walk her dog. She keeps a close eye on air quality and uses her inhaler before she heads out.

Last week, she called her pulmonologist to get a new prescription. For days, the line was always busy. Unnerved, she wondered if she might run out.

“It was a relief to finally get through,” she said.