Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Even if you wanted to, it’d be impossible to avoid all the scary numbers floating around about the potential toll of the coronavirus. And even though I write about science for a living, I’ve been struck by the sheer range of projections—I’ve seen estimates that say anywhere between 200,000 and 2.2 million Americans could die depending on the virus’s characteristics and what actions the federal government takes—and how helpless they make me feel. I keep thinking, what the hell are we supposed to make of all these stats? What good do these projections even do?

To be clear, I recognize that projections are scientifically important. They are also powerful tools to inform public health officials and governments as they make decisions and implement policies. (Case in point: Reporting suggests that an Imperial College London study was what helped finally spur the Trump administration into a more meaningful coronavirus response.)

But as someone out in the world just trying to internalize what the hell is going on and what we should anticipate moving forward, I’ve wondered if there’s a better way to talk about the coronavirus. What kinds of communication can actually push people to take action—to, among other things, socially distance, wash their hands, and not freak out? I recently posed this question to risk communications expert Dominique Brossard, a professor and chair in the Department of Life Sciences Communication at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

When faced with mind-boggling projections, she says, there are two types of reactions that people typically have: They either get scared and anxious, or they dismiss the information because they find it unbelievable. Neither is good, of course. While some research suggests that a certain level of fear can lead to what Brossard calls “protective behavior,” there’s a fine line to walk between being honest and transparent with people and needlessly scaring the bejeezus out of them.

Brossard has spent nearly two decades studying how people process scientific information and the best ways to communicate in times of a public health crisis. She emphasized there is no one-size-fits-all approach to risk communication, but she shared some of her tips for how to talk about—and better yet, understand—what’s going on with COVID-19:

Find ways to connect the numbers to a person’s real life.

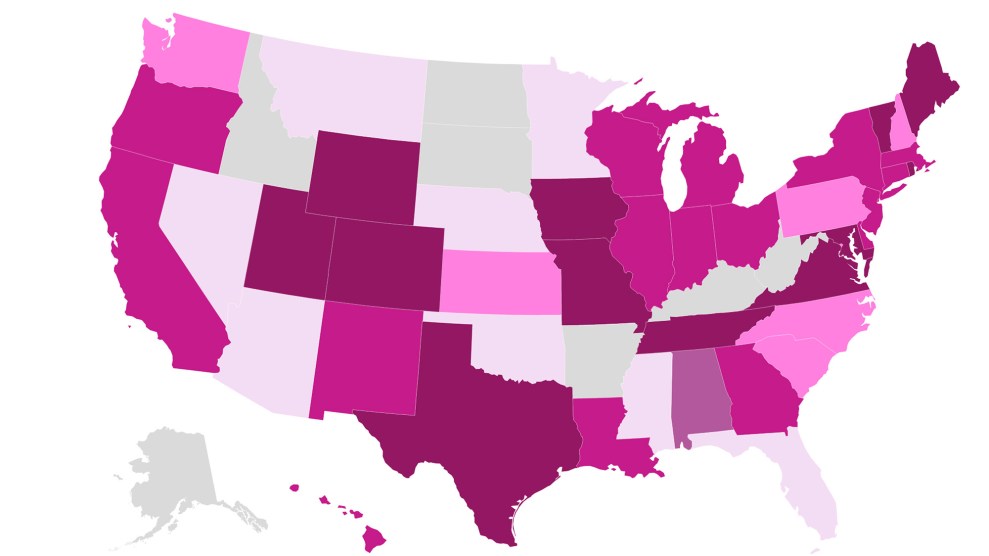

People’s perception of risk typically comes from qualitative thinking more than quantitative. For example, Brossard says, you could tell someone that 500,000 people are going to die from COVID-19 in the United States. “That’s kind of abstract,” she notes. It’s hard to internalize. “Very often, the problem that we have with those type of statistics is that, yes, they should generate fear. But if people cannot connect it to something that they are familiar with” then it may not have an effect on them. Instead, she says it can have a bigger impact to say something like, “500,000 could die, including your grandmother,” or “people will die in every state including yours.”

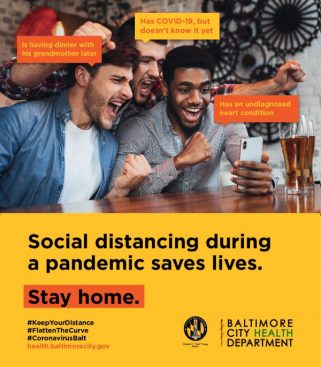

A recent public service announcement from the city of Baltimore, which encourages people to stay home to prevent the spread of COVID-19, uses this approach. On the poster, there’s a picture of three men watching something on a cellphone and cheering. On top of their images, annotations reveal that one of them “has COVID-19 and doesn’t know it yet.” Another “has an undiagnosed heart condition.” And the third is “having dinner with his grandmother later.” It’s a jarring—and memorable—image.

“What’s much more powerful than numbers is if you can put a face on something,” Brossard says. Baltimore’s poster, she says, makes you think of someone you know, perhaps a friend. “That’s that idea, making it relevant in a way that people can identify with it.”

Another effective option is putting the number into a smaller fraction—for example, “at least one out of every two people will get the coronavirus, some experts project”—or comparing the number to the population of a city—”500,000 people, which is roughly the population of Atlanta”—can help, she says, “give a sense that these are real people.”

Statistics can cause anxiety and fear. Hope can be a more powerful tool to get people to take action.

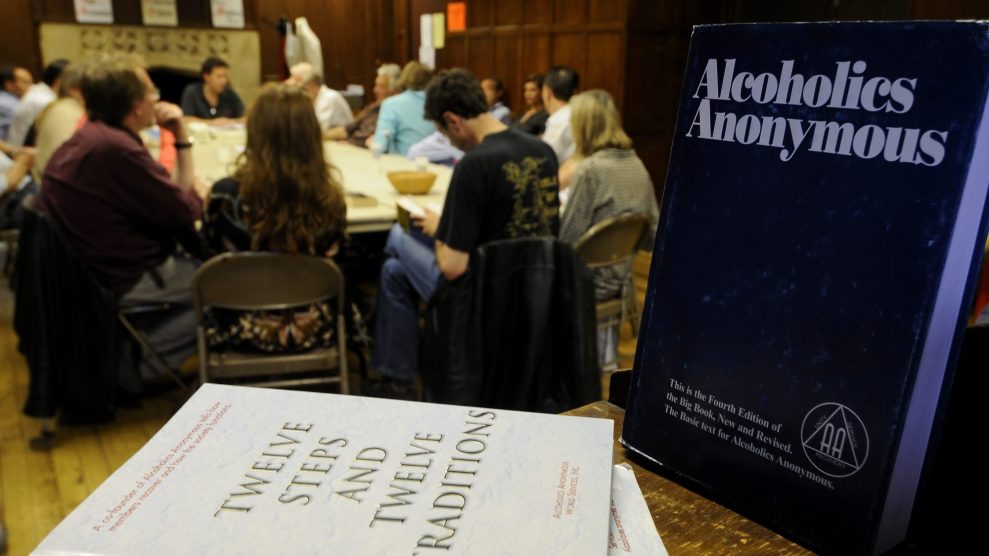

Hope can empower people. Stories “showing how people are coming together to address the issue of social distancing, how neighbors are helping each other with food, with child care, how people are taking seriously that idea of social distancing,” Brossard says, can give people a sense of self-efficacy and inspire them to take similar action.

Take this 2019 study on climate change behavior: Researchers surveyed 1,310 people about their feelings of hope and doubt on the subject of climate change. Participants who felt “constructive hope” (for instance, feeling that “people—individually and collectively—can reduce climate change”) and recognized the reality of the threat were more likely to support climate policy and political action. In a second survey of 674 people, respondents reported that overall their feelings of hope came from “individual and collective actions, and from positive observations of behaviors rather than from negative pressures to respond (such as extreme weather events) or from developments in science and technology,” the study authors write. In other words, people’s feelings of hope grew from seeing other people’s positive actions, not from scary events.

I also spoke with associate professor of biostatistics Hakan Demirtas and Mark Dworkin, a professor and associate director of epidemiology, both at the University of Illinois at Chicago, last week; they each echoed this sentiment. While we shouldn’t ignore the big coronavirus projections, they worry that focusing on them may raise public anxiety at a time when anxiety is already high. “I think the big message here for the public, in putting this into perspective, is: Stop focusing on the numbers,” Dworkin says. “Let the experts and policy leaders focus on them. The numbers are just raising our anxiety, right?”

“It’s an echo chamber in the media right now with these numbers,” Dworkin adds. “It’s numbers about death and tragedy and it’s really hurting people while it’s informing them…How many stories have you read about the heroic efforts of nurses and doctors versus how many times have you heard about the death counts rising and the doubling of the numbers and the horror show?”

Consider the messenger; they can be even more important than the message

Another key factor in generating action is who or what is sharing the information. It’s more or less common sense, but it’s crucial: If the messenger is someone or something people already don’t trust, they’re more likely to dismiss it, Brossard says. “We tend to accept information that fits our beliefs, and we tend to reject what doesn’t fit.” This is called “motivated reasoning.”

Surveys show, for instance, that some Republicans can accept the principles of science—physics, chemistry, biology—but can also deny that climate change is happening. That is, climate change doesn’t fit their belief structure. The same is true, Brossard argues, of some liberals who may think genetically modified foods are unsafe to eat, despite what the science tells us. If two different messengers tell you the same thing and you don’t trust one of the messengers, you may discard their message while accepting the other, according to Brossard. “Very often, trusting the messenger is more important than the content of the message itself.”

For example, Brossard and other researchers published a study in 2018 that showed that when people were presented with the same data (in this case, about nuclear technology), participants who were told the data came from MIT were more likely to find the information credible than the participants who were told it was from the Department of Energy. This is likely in part because Americans tend to trust scientists (and not necessarily the government). According to a new Pew poll, 86 percent of Americans have “a great deal” or a “fair amount” of confidence in scientists to act in the public interest. (Unfortunately for all of us, as my colleague Mark Helenowski points out, Trump has regularly ignored the advice of scientific experts.)

Look to the past for ways to learn from our mistakes

In times of crisis, what didn’t work before probably won’t work now. Brossard suggests the initial communications around climate change are one powerful example. “Who was, right away, the spokesperson for climate change? Al Gore”—someone who had just come off a contentious presidential election that went all the way to the Supreme Court. “It was framed as a Democratic issue.”

But that isn’t the only lesson from past failures regarding climate change. The issue was also framed as an environmental issue that in no way connected to the individual lives of American people. Among the first images employed to communicate the risk was a polar bear on a melting ice cap. “That was kind of like the iconic image that was used to communicate with climate change. Remember that? But people go, ‘Oh, poor polar bear,’ and went on with their lives.”

(Of course, these are not the only reasons American’s can’t agree on climate change action; don’t forget the powerful industry interests that worked to silence the warnings of scientists for decades.)

In the same way, effective COVID-19 messaging will need to connect to people’s realities, be framed as a nonpartisan issue, and instill hope. We have a chance to learn from past misfires, Brossard says. “I would say climate change communication has been a fiasco. We should be doing so much more now than we’re doing—certainly, lessons have to be learned.”