One of Dijon Kizzee's uncles grieves at a makeshift memorial where Kizzee, a 29-year-old Black man, was killed by Los Angeles sheriff's deputies in South Los Angeles.David McNew/Getty Images

Dijon Kizzee, a 29-year-old Black man, was riding his bicycle through South Los Angeles on Monday afternoon when he noticed two sheriff’s deputies trying to stop him. He got off the bike and started running.

The deputies say they wanted to stop Kizzee because he was riding in violation of vehicle codes. They chased him down the street. A scuffle ensued, and Kizzee dropped a jacket on the ground; wrapped inside it was a gun. When the deputies spotted the firearm, they shot him multiple times, killing him.

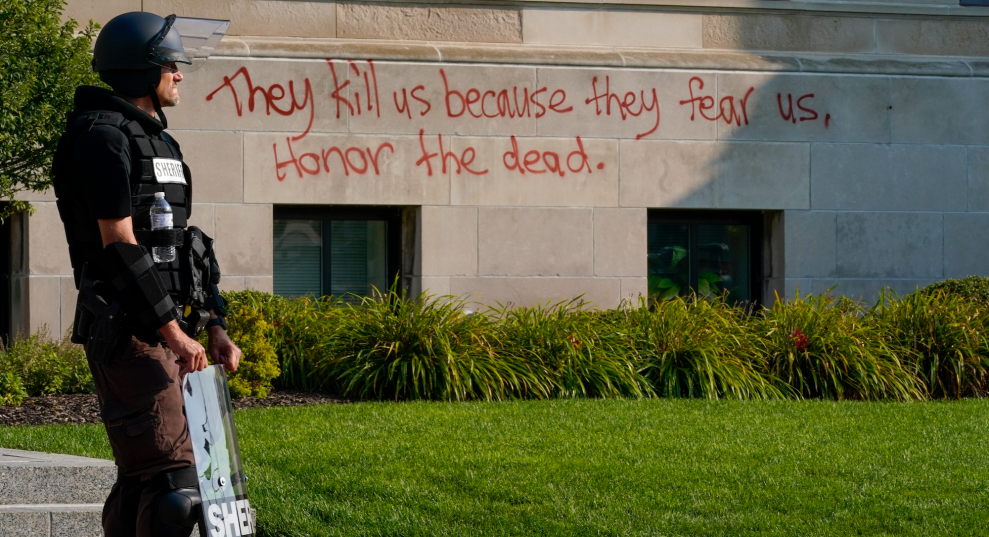

The sheriff’s department hasn’t specified which vehicle codes Kizzee allegedly broke, and a spokesperson claims he reached toward his gun before the deputies shot him, something that can’t clearly be confirmed by the available video footage. The killing, which came about a week after an officer shot Jacob Blake several times in the back in Wisconsin, has spurred renewed protests in Los Angeles amid a nationwide movement to stop police violence against Black people.

Kizzee’s tragic death is also a reminder that across the country, police officers who are already disproportionately stopping Black people for driving their cars or walking down the street or simply going about their lives are also disproportionately stopping them for riding their bikes.

Kizzee is not the first Black man to die as a result of one of these stops. In August 2014, the same month a Ferguson cop shot Michael Brown, who had been walking down the street, a sheriff’s deputy stopped Dante Parker, 36, while he was riding his bike in Victorville, California. The deputy said Parker matched the description of a burglar, and after struggling to detain him, officers used a Taser about 25 times, killing him. The district attorney’s office declined to press charges against the deputies, saying Parker died because he was also on drugs after an autopsy report showed he had PCP in his system.

There’s no nationwide data on the dangers of biking while Black, but studies in individual cities reveal an alarming trend. In Oakland, California, Black people accounted for nearly 60 percent of cycling stops by police from 2016 to 2018, making them over three times likelier than white cyclists to be pulled over, per public records obtained by Bicycling magazine. The situation isn’t much better in Chicago, where 56 percent of all bike tickets were issued in majority-Black neighborhoods in 2017, even though US census data shows that bike commuting is more popular in the city’s majority-white neighborhoods, according to the Chicago Tribune. In Washington, DC, Black people accounted for 88 percent of cycling stops from 2010 to 2017, though they make up about 45 percent of the district’s overall population, according to more public records obtained by Bicycling. And Black people in DC were far more likely to be stopped for the vague reason of appearing “suspicious.”

Florida offers more disheartening statistics. A 2015 investigation by the Tampa Bay Times found that Black people accounted for 8 out of 10 cyclists who were ticketed in the city for problems like riding with someone on the handlebars. After Fort Lauderdale began requiring residents to register their bicycles with the city, the Broward Palm Beach New Times found that Black cyclists received 86 percent of cycling citations from 2010 to 2013, even though Black residents were significantly more likely than white residents to register their bikes.

It’s hard to get a broader look at the problem because many cities don’t share data on the race of cyclists stopped by police. Bicycling requested public records from 100 of the most populous cities, and only three complied. Los Angeles, where Kizzee was killed, has been a holdout. According to the Associated Press, the sheriff’s department has not provided these statistics, and the police department does not break down its data about vehicle stops by category.

County Superviser Mark Ridley-Thomas told the news wire that since Kizzee’s death, he’s heard stories of other Black people who were allegedly harassed by police while biking. “Right now, I’m sad, and I’m mad at the same time,” Kizzee’s aunt Fletcher Fair told the Los Angeles Times. “We are tired. We are absolutely tired.” It was the second fatal shooting by sheriff’s deputies within a block during just a few months.