A pedestrian walks past the Federal Election Commission's headquarters in Washington, D.C.Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Democrats always have had a complicated relationship with campaign finance law. The party has long railed against the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision and the deluge of money it unleashed and vowed to clarify and better enforce the rules on who can give and how much. But at the same time, Democrats have often raised big money in the post-Citizens United era—emboldening political operatives and the more pragmatic strategists in the party to push the envelope and expand their fundraising efforts. The Republicans were not troubled by any constraints, so, today, campaign finance transparency continues to be the domain of liberals.

Yet, the tension between the laudable attempt to crack down on special interests, and the reality that Democrats need funds to compete with Republicans is playing out in the newly reconstituted Federal Election Commission. With a new Democratic commissioner appointed this summer, transparency activists hoped efforts to use the commission to turn off the money spigot would be reinvigorated.

With the three Democratic commissioners and the three Republican commissioners deadlocked for years, the agency has appeared moribund and often hapless, failing to reach any meaningful consensus on major enforcement issues. During the 2020 election, the FEC didn’t even have a quorum—Republican members kept resigning, and new ones weren’t appointed quickly enough, leaving the federal watchdog group powerless as it watched the most expensive election in history surge past.

Things have changed; there are now six commissioners. But on the eve of what will soon become the most expensive mid-term election, transparency activists are livid over the actions of the commission’s newest Democratic member who joined the FEC in August. Biden appointee Dara Lindenbaum, a campaign finance attorney, has strong liberal credentials but has several times voted with the Republicans to dismiss enforcement cases that advocates had hoped would be pushed to the courts to decide.

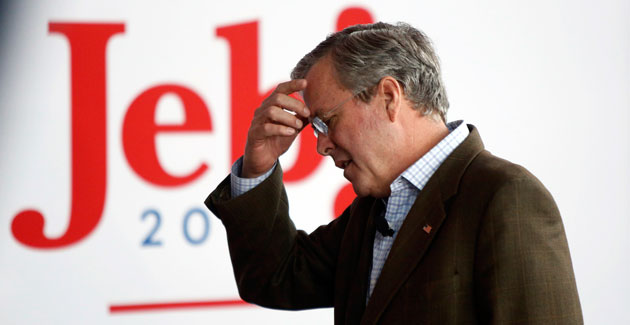

One notable case has particular relevance as former president Donald Trump has consistently teased the possibility he will run for office again. At issue is a complaint that was filed against Jeb Bush’s political operation over his preparations for the 2016 campaign. Campaign finance law says that anyone running for office must file regular disclosures and it limits the amount of money a candidate can accept from donors—but the rules don’t apply to someone who hasn’t formally declared their candidacy. In 2016, Bush tested the limits of those rules, traveling the country with a super-PAC and eventually raising more than $100 million to aid his campaign before officially announcing. Not declaring himself a candidate allowed him much greater freedom to talk to donors and solicit big checks for his cause. To transparency watchdogs his actions were a blatant and obvious charade—everyone knew that Bush was going to run. But he wanted to do as much as possible to expand his war chest to such an extent it would intimidate opponents out of the race before it even began.

The complaint, first filed in March of 2015, languished at the FEC, with periodic efforts to vote for some sort of enforcement action. In the end, Jeb Bush’s presidential campaign and efforts to prepare for it were all for nothing. But for transparency advocates, it still seemed like an important opportunity to make a strong statement about what is and isn’t acceptable for a candidate to do in the run-up to an election. After failing to get enough votes to take an action in the case, finally, in August, the FEC commissioners voted 4-1 to close the file (one Democratic commissioner abstained). Ellen Weintraub, the lone vote against dismissal and one of the most vocal Democratic members of the commission wrote of her disgust about the vote to toss the case, in a statement accompanying the decision.

“Of all the meritorious enforcement complaints Republican commissioners have blocked the Commission from pursuing over the years—and they are legion—my former colleagues’ refusal to enforce the law in this matter ranks as among the most egregious,” she wrote.

Weintraub argued, despite Bush’s eventual flameout in the face of the Trump candidacy, just letting this old case slip away with no action would have broader consequences.

“If you think this case is a quaint relic of a long-gone election, wait ’til you see the impact this kind of gamesmanship could have on the 2024 election,” she wrote. Following Lindenbaum’s votes on the Bush case and several others, Adav Noti, a long-time FEC staffer who now works as an attorney at the campaign finance watchdog group Campaign Legal Center, did the digital equivalent of publicly throwing his hands in the air with disgust.

This is unfortunate because it confirms suspicions about the new @FEC majority, but then again, is the FEC is even relevant anymore?

For those of us actually enforcing campaign finance law, filing an FEC complaint is just a mildly irritating box to check on the way to court. https://t.co/w2xjckhdwA

— Adav Noti (@AdavNoti) October 2, 2022

“Is the FEC even relevant anymore?” Noti asked. “For those of us actually enforcing campaign finance law, filing an FEC complaint is just a mildly irritating box to check on the way to court.”

Irritation with the FEC is not unique—liberals have been kvetching about its inaction for years and conservatives don’t have a very high opinion of it either—but Noti’s Tweet was a surprisingly public cry of exasperation from a community that, despite its concerns, has also tried to focus on fixing the FEC—not walking away from it.

In the past, when the FEC failed to reach a decision about enforcing a matter, outsiders like Noti sued the agency and asked a judge to force its enforcement of a rule. And that’s exactly what Noti’s group and others like it have been doing for several years now—aggressively pursuing cases in court that the FEC has seemed unable, or unwilling, to act on. For example, among the slew of lawsuits Noti’s Campaign Legal Center and other transparency groups have filed to force the FEC to take enforcement actions, is one to compel the FEC to act against the Trump campaign. At issue is huge sums of money the campaign apparently funneled through his former campaign manager Brad Parscale’s network of companies to pay vendors, which in effect hid who really was working for the campaign.

Recently, the strategy of taking it to court had become the de facto approach for Democrats, led by Weintraub. If the commission deadlocked on an enforcement matter—like the Jeb Bush complaint or the Trump campaign’s dubious spending by Parscale—the commission’s own inaction actually became part of moving forward.

Democratic members began refusing to dismiss matters that had deadlocked. Instead, they dragged on with no answer, and then groups like Noti’s were able to file lawsuits asking a judge to force the Commission to act. Democratic commissioners then could block an attempt by the FEC to send lawyers to defend the agency in court. “It’s a depressing comment on the state of our campaign system,” Noti says. “We don’t file complaints anymore because we think the FEC will do anything, we file complaints because it’s a procedural step.”

If the FEC doesn’t defend itself, the law allows outside groups to sue the group accused of breaking the rules directly. For example, in 2018, the government watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) sued Crossroads GPS, a conservative group started by Karl Rove. They charged that Crossroads GPS failed to properly disclose donors and won a ruling that non-profits must disclose their large donors if they run an ad attacking or promoting a candidate.

Even if the system wasn’t functioning remotely as it was designed to, transparency activists said it was starting to work to uphold the law because even if the FEC wasn’t explicitly doing its job, by filing lawsuits, someone else was going to make them.

The appointment of Lindenbaum changed everything. On four matters in September, she voted to dismiss enforcement cases that had deadlocked. Lawsuits are still possible, but her actions instantly took the elaborate strategy Democrats had been using off the table.

Lindenbaum, who is currently the vice-chairman of the commission, spoke to Mother Jones jointly with Republican commisioner and current chair Allen Dickerson. She said people who accuse her of not defending transparency or being against enforcement are missing the point of what she believes her role should be. “The ones that you should really talk to are those who are parts of the campaigns—they are the ones who are actually affected by the rules and regulations and the ambiguity,” Lindenbaum says. “There are organizations that are part of the campaign finance ecosystem that may not like what we’re doing here, and they may have their reasons, but I think most people who are affected by this agency are excited to see us promulgate rules, and give a real clear majority on things.”

Dickerson added, “Most of the people under our jurisdiction are pretty happy with it.”

In other words, like it or not, the FEC is getting things done, which is to say that the FEC is ruling on cases and moving things along. That appears to be what both Democrat and Republican campaign fundraisers and operatives want. Neither party is interested in an intricate defense of transparency using arcane commission rules; they want to raise money as much money as possible in order to win elections.

“They want the rules to be evenly applied and make sense and be clear,” says Dickerson. “And yes, you’re going to have people who have very strong feelings about what those rules mean, but the vast majority of people actually in the field care much more about the rules being applied and being clear.”

Lindenbaum and Dickerson say that by finding a kind of bi-partisan agreement they are getting the FEC moving again—even if it’s not to the transparency crowd’s liking. Weintraub at least agrees that there is some common ground when it comes to shedding oversight. Take the lack of clarity on how closely politicians can work with outside groups like super-PACs. According to the Citizens United decision, huge sums of money were permissible as long as the people spending it didn’t coordinate with the candidates. But now, loopholes seem to abound and Congressional leaders on both sides work closely with super-PACs to try and manipulate elections to help allies and hurt opponents. The FEC’s failure to close the loopholes—either by enforcing complaints against them or writing new rules—is benefitting politicos on both sides, Weintraub says.

“This is not something that only one side is doing, everyone is taking advantage of them,” she says. “I think, if we were a well-functioning agency, we would have tighter rules on coordination.”

The problem is more fundamental than just the partisan dysfunction that has crippled the agency’s ability to operate in recent years, she notes. From her perspective, she says, “We don’t have a majority of commissioners who are dedicated to enforcing the law.”