Mother Jones illustration; Courtesy of Emory University

As the world grapples with the devastation of the coronavirus, one thing is clear: The United States simply wasn’t prepared. Despite repeated warnings from infectious disease experts over the years, we lacked essential beds, equipment, and medication; public health advice was confusing; and our leadership offered no clear direction while sidelining credible health professionals and institutions. Infectious disease experts agree that it’s only a matter of time before the next pandemic hits, and that one could be even more deadly. So how do we fix what COVID-19 has shown was broken? In this Mother Jones series, we’re asking experts from a wide range of disciplines one question: What are the most important steps we can take to make sure we’re better prepared next time around?

Last week, the New York Times hit us with some bad news: Reaching “herd immunity” against the coronavirus may no longer be a possibility, largely due to vaccine hesitancy and a rise in more contagious variants. “[D]aily vaccination rates are slipping,” science reporter Apoorva Mandavilli wrote, “and there is widespread consensus among scientists and public health experts that the herd immunity threshold is not attainable—at least not in the foreseeable future, and perhaps not ever.” In short, the message was, COVID is here to stay.

As Mandavilli notes, public health officials in the US, including Dr. Anthony Fauci, once pointed to herd immunity as the path out of this pandemic. If enough of the population was vaccinated—maybe 60 or 70 percent or more—the theory was, the virus would have nowhere to spread. COVID cases would fizzle out. And we could have our lives back. Herd immunity seemed to be our ticket to normalcy. But has the train already left the station?

The short answer: No. It may not as simple as hitting a secret magic number that stomps out the virus’s spread. But, as Mandavilli reports, with vaccinations, the virus can be managed. “You vaccinate enough people,” Fauci told the Times last week, “the infections are going to go down.”

Still, after reading the report, I was left with more questions than answers. If herd immunity is no longer the goal, what is? What does a world in which we do not achieve herd immunity look like? What does a “manageable” number of cases even mean? To put it bluntly, what is there left to hope for?

What experts tell me is that herd immunity, in the case of COVID, is really just a concept—not a singular goal. It’s not the end-all, be-all, a return to normalcy is not out of the question, and yes, there are many reasons to be hopeful. (We already have 262 million of them—and counting—in people’s arms.)

Take, for instance, the words of Dr. John Swartzberg, a clinical professor emeritus specializing in infectious diseases and vaccinology at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, who sent me a few thoughts via email:

Think about influenza. Every year it visits us. In a good year, it kills 15K-20K Americans. In a bad year, 50K-60K. We get our annual influenza vaccine (40% to 60% effective in preventing disease) and go on with our quotidian existence.

Likely, Covid-19 will be endemic (it will visit us every year) like influenza. It may be less, the same, or more virulent than influenza.

But, two of our vaccines give us 90% to 95% protection against disease and nearly 100% against hospitalization and death. If a variant comes along that does not respond to our vaccines, we’ll make a new vaccine (we can do this quickly).

We can and will deal with this.

On Twitter, Dr. Ashish Jha, a physician and dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, offered a similarly optimistic view about what to expect next: “No we may not hit herd immunity,” he wrote, but “infection numbers will be low,” “vaccinated folks will be mainly safe,” and with better treatment, “infections may become less problematic.” Life will return “to a recognizable normal.”

Folks being critical or misunderstanding this very good @apoorva_nyc piece

5 points that this piece pulls together nicely

1. Last year, we all assumed herd immunity threshold (HIT) would be 60-70%. Now clear its higher

This is not tragic

Threadhttps://t.co/fEp4ak0MxN

— Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH (@ashishkjha) May 3, 2021

To get more detail about what it means to say goodbye to herd immunity, I spoke via Zoom with Dr. Carlos del Rio, an infectious disease specialist and epidemiologist at Emory University. As del Rio explains, the goal of herd immunity was always a fickle one, COVID is something we may need to learn to live with, and this new normal may mean treating COVID risk like the weather.

On what “herd immunity” is—and isn’t: I think some people have misinterpreted herd immunity. People have seen it almost like the endpoint. I joke with people that when we get to herd immunity, people were thinking that we’re gonna have Dr. Fauci on top of an aircraft carrier with a sign that says “mission accomplished.” It’s not going to be that, right? Herd immunity is a concept in virology but is not a goal in itself. And what it means is, between people infected and people vaccinated, you decrease the chances of transmission. But it’s not a goal. It’s not like we get to a point that we say, “Oh, we reached herd immunity, we’re done. Let’s move on to something different.”

On where we go from here: An estimated 30 percent of the US population has been infected, another, say, 40 percent has been vaccinated. Then we have about 20 percent who are children whom you cannot vaccinate, and about 20 percent who are still on the fence about vaccination. So, you’re going to have a good 30 to 40 percent of people who are not going to be vaccinated. And I think what we’re going to continue seeing in the US pretty soon—it’s already starting to happen—is that we’re going to have a continuous trickle of cases. Currently, we’re stable at around 40,000 cases around 600 deaths per day. The question we need to ask ourselves is, as a society, what’s the acceptable number of cases and deaths? How much risk are we willing to accept and what strategies are we willing to implement in order to open the economy and go on with our lives? Those are those going to be the difficult questions.

On moving forward by treating risk like a spectrum: I think people are going to have to learn to evaluate their risk, and it’s not going to be the same in every community. And it’s not going to be the same in every circumstance. We’re all going to have to learn to live with COVID.

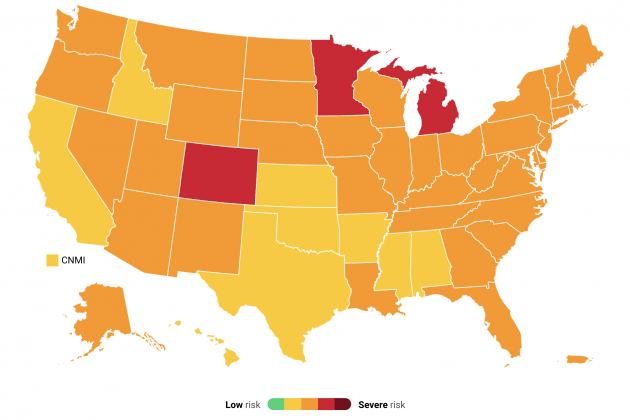

I like to look, for example, at COVID Act Now.

Screenshot from Friday, May 6

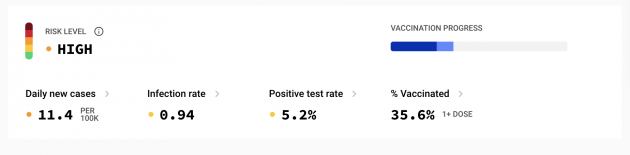

The best [category] is green. No state in the country right now is green. Yellow is the second-best. Orange is the third best. Red is bad. And dark red is really bad. When I look at my state of Georgia, we are at 11 cases per 100,000.

Georgia’s risk level. (Screenshot from May 6)

Covid Act Now

Once we get under 10 [cases per 100,000], we’re going to be in yellow. We’re very close to getting to yellow. The positivity rate is 5.2 percent. I would love to see that under 5 percent. In Georgia, you may be less likely [than in other states] to get infected, therefore, you’re more likely to be able to go outside and not wear a mask. Now, will I go to a 10,000, 20,000, 30,000 person event indoors? I’m not sure. If I go, I’d probably wear my mask. But will I go to an event outside? Yeah, I probably would.

I think at some point in time, we’re going to have to use a combination of how much disease is in a certain community and how many people are vaccinated in their community to decide what’s safe and what’s not safe. It’s almost like looking at the weather report in the morning: Do I have to pull out an umbrella or not?

On vaccination being a global fight: It has to be a global effort because countries are not independent from each other. We’re all interconnected. We’re all traveling. I find it ludicrous when, quite frankly, when the US government says, “We’re gonna suspend travel from India, except for US citizens.” I understand you cannot prevent US citizens from traveling from India. But the reality is, the virus couldn’t care less what color is your passport. You can’t control this virus by just focusing only on your border.

On the potential of variants getting around our vaccines: So far, for the variants that we have, the vaccines work. Yeah, there could be variants that are not susceptible to the vaccines, but I’ll worry about that when it happens, honestly. My biggest concern right now is, let’s get people vaccinated.

The number of people [who are getting] vaccinated is dropping in our country, honestly, in a very scary way. The daily vaccination rate has fallen by about 50 percent since the peak on April 13. That, to me, is my biggest concern. It’s not variants, it’s vaccines. We have to get people vaccinated.

On the worst-case scenario and the best-case scenario ahead: I think the worst-case scenario is called India. That’s a nightmare. And I think that’s something that should worry us all. You talk about the emergence of variants? That’s how variants emerge, when there’s uncontrolled transmission. Hopefully, [uncontrolled spread] will not happen in this country again because we have already a big chunk of the population vaccinated.

My best-case scenario is when COVID deaths become rare. Today, at my hospital was a happy day, because we had been hanging around 40 hospitalized [COVID] patients, and today we went down to 27. And that felt really good. At one point, we were at 200. So the fact that we were down to 27, it feels like—there was a sense of relief. I think if we can bring [US] deaths under 100 per day, I think we’re all going to be in a much better place.