As a news editor here at Mother Jones, I don’t usually write about our internal business operations. After four years as a reporter for the magazine, I now spend my days working with our staggeringly talented writers to plan their reporting and edit their stories. Since “news” is in my title, I look at how we can jump onto the craziness of the moment, but also spend a lot of my time on the unique investigative work that we really pride ourselves on, which has run a wide gamut, including how Amazon exploits its workers, profiles of politicians like Jaime Harrison before the rest of the national media caught onto his rise, investigations of questionable fundraising companies, and explorations of how Donald Trump has made life hell for federal whistleblowers.

But over the past three years, I’ve also been one of the co-chairs of Mother Jones’ union, devoting countless hours of my life to protecting the interests of more than 50 of my colleagues. It’s easily been one of the most rewarding things I’ve done in my decade as a professional journalist. As befitting a magazine named after a badass union organizer, our management is usually pretty receptive to hearing input from workers, but of course we have our disagreements, and the union plays an important role in elevating concerns that newsroom leaders might otherwise be unaware of.

It’s thanks to those dual roles of editor and union rep that I was so enraged when it was revealed that Facebook had changed its algorithm in such a way that boosted conservative outlets like Ben Shapiro’s Daily Wire at the expense of progressive outlets, specifically us. They even made a slide deck to show which publishers would benefit and which would be hurt, as MoJo‘s editor-in-chief, Clara Jeffery, and CEO, Monika Bauerlein, discovered. “To be perfectly clear,” Clara and Monika write, “Facebook used its monopolistic power to boost and suppress specific publishers’ content—the essence of every Big Brother fear about the platforms, and something Facebook and other companies have been strenuously denying for years.”

As my colleague Ben Dreyfuss, who’s overseen our Facebook presence, put it, “It’s difficult and disheartening to keep running into walls, and to learn that the walls were placed there intentionally, so my colleagues and I would be stopped as we tried to promote our magazine’s work, makes me livid.”

It’s hard to calculate exactly what these changes mean for Mother Jones—how many people did not see our articles, how many potential subscribers and donors we did not reach—but a very conservative estimate of just the loss in advertising revenue is more than $400,000 between the time those algorithm changes were implemented and the end of our last fiscal year, this June. And it’s that specific number that particularly ate at me given my role with our union: In June, we specifically worked with management to trim our payroll by $400,000 to make ends meet for our 2020–2021 fiscal year.

I spent much of this spring working with union co-chair Nathalie Baptiste (go read her stuff, she’s an amazing reporter) to negotiate a new collective bargaining agreement. It wasn’t always easy (and not just because we had to scuttle in-person negotiations and switch to Zoom thanks to the pandemic). After all, we’re a small nonprofit with a limited budget, so wrestling with just how much money Mother Jones could afford to spend on severance should we ever have layoffs was inevitable. But in the end, we came to a consensus pretty easily and added a ton of benefits to make Mother Jones a better place for everyone who works here: doubling our parental leave to four months; new plans to improve staff diversity; mental health benefits to correct for the health insurance industry’s failure to build parity; and nearly double the previous severance benefits in most instances.

But shortly after Nathalie and I had a virtual toast to wrap up the CBA, that last provision became all too relevant: Amid the pandemic, Mother Jones’ budget was in a more precarious position and management came to us with a tough question. They had already made every cut to the budget they could think of without affecting jobs, but there was still a gap they couldn’t square—and it was just about $400,000.

Nathalie and I pored over the budget, trying to brainstorm ways to save more money on the margins—we’re using fewer paper clips while working remotely, so that must save some money, right?—but in the end it was clear that all the rocks had been turned over and the $400,000 had to come in some form or fashion from payroll. We’re a lean organization, so besides benefits and salary, there’s not much give in the budget. Unlike Facebook, we never had frills like a bike repair shop or a full arcade, and our snacks—back in the Before, when we still went to the office—were limited to gummy bears and pretzels. Instead we invest in our workers and focus on spending what we need to produce the journalism you come here to read.

That $400,000 inevitably meant real hardship. When we sat down to discuss the budget with Mother Jones’ management the options were stark: If we couldn’t find agreement on pay cuts affecting the majority of staff, we could be forced (after factoring in severance) to lay off as many as six people. That might not sound like a huge number, but at a place where just over 90 people work, it would be truly devastating on a personal level, and would severely limit the amount of quality, high-impact journalism we’d be able to put into the world at a time when jobs everywhere are precarious and journalistic feet on the street are more important than ever.

Thankfully Mother Jones’ leaders didn’t want that option and neither did our union. So we worked together on pay cuts. We settled on a progressive scale of pay cuts with a floor exempting the bottom half of union members. As I mentioned earlier, we’re a lean nonprofit and no one here is making top-of-the-line media salaries or even comparable nonprofit salaries—from our entry-level reporters to our CEO and editor-in-chief. Working for Mother Jones offers us the chance to focus on the sort of in-depth reporting that inspired all of us to become journalists in the first place. But our relative leanness also means that extra cuts aren’t easy to come by or deal with when they have to happen. The union also agreed to forfeit our guaranteed annual cost of living adjustment (always the first benefit I’d mention when we hired someone new on why our union was so awesome) and our 401(k) match.

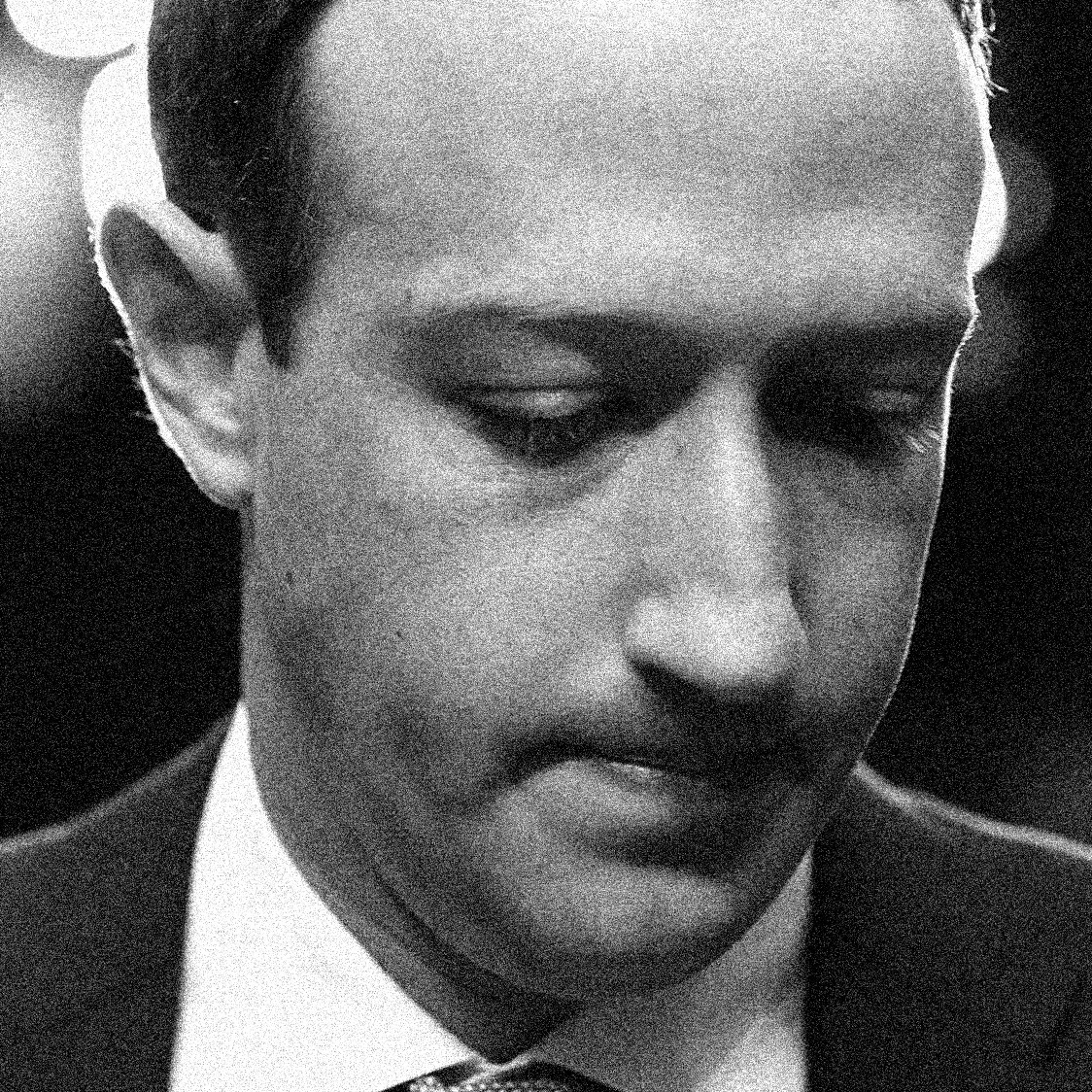

After all of that, it was galling to hear that Mark Zuckerberg—a man who has spun his dorm-room version of Hot or Not for rating female classmates’ appearance into an estimated net worth of over $100 billion—personally signed off on a plan to limit our journalism from being read by our fans (since after all, our stories only show up in your Facebook feed if you’ve liked our page or a story was shared by one of your friends). Meanwhile, Zuckerberg was having conservative pundit Ben Shapiro over to his home for dinner (unclear if they killed the night’s feast together first) despite Facebook’s own fact-checkers flagging Shapiro’s Daily Wire as a peddler of misinformation, whereas we’re a publication that has staked our reputation on building a robust system of internal fact-checking. And while yes, we are up front about the fact that our journalism comes from a set of values, those values are not driven by partisan politics. I spent a good chunk of the summer working with a freelancer on a great story exploring how online school ratings could be exacerbating segregation. Can you imagine Shapiro publishing something investigative that’s not just trying to fan the flames of the right’s political grudges?

Thankfully, unlike many other news outlets, we aren’t overly reliant on advertisers, so Facebook’s tweaks didn’t decimate us. I’ve found myself too often texting friends this year to see if they still have a job when another publication announces a round of layoffs, putting in perspective that our cuts aren’t so bad, all things considered. And that’s because we make most of our money from you (yes you), our readers. Some of you chip in a lot, some of you just $10 on top of your subscription, but it all adds up to a powerful model for keeping nonprofit journalism alive.

Maybe it’s my inner Minnesotan, but I’ve always felt a bit icky asking for money. And I’d much rather spend my time thinking about the important investigative stories we have in the works than how my salary gets paid. But these are dire times, and I don’t ever want to have to contemplate layoffs in my role as union co-chair, so if you can, please chip in. After all, is this really the type of person we want deciding the future of the journalism industry, or wouldn’t it be better if readers and journalists got to make that decision?