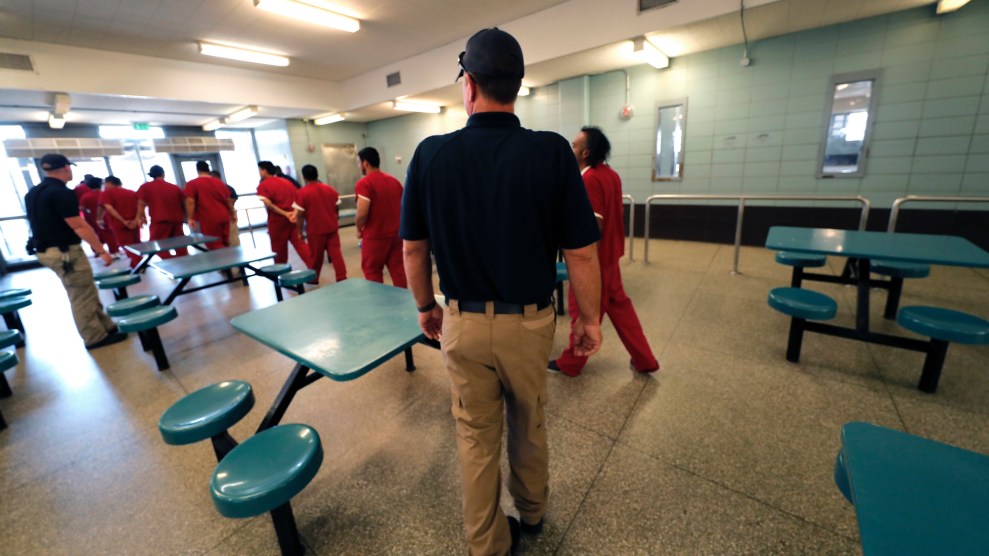

People in Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody participate in outdoor recreational activities at the Winn Correctional Center, a for-profit prison in Louisiana used by ICE, in September.Gerald Herbert/AP

Guards at an immigration detention center in Louisiana pepper-sprayed asylum seekers this week who were demanding their release, according to two of the protesters.

Menoh Ernest, a Cameroonian asylum seeker at the Richwood Correctional Center in rural northern Louisiana, said about two dozen people were pepper-sprayed on Monday night. Guards, he said, placed their knees on demonstrators’ necks while restraining them. Another Cameroonian asylum seeker who has been detained for nearly 18 months, whom I’ll call Wilfred because he did not give permission to use his name, reported that he still had bruises and trouble swallowing after guards “climbed” onto his neck.

The incident is the latest in an extensive pattern of Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainees being pepper-sprayed as they push for their release and safer conditions during the coronavirus pandemic. Hundreds of detained immigrants and asylum seekers have been exposed to pepper spray on at least a dozen occasions since late March. Unlike with deaths in ICE custody, the agency does not have a policy of disclosing uses of force, including the use of chemical agents, so it’s possible that some incidents have gone unreported.

ICE spokesperson Bryan Cox confirmed the pepper-spraying, but he said in an email that the two men’s accounts left out “critical information.” The pepper-spraying, he said, only “occurred only after a group of detainees refused repeated commands from facility staff and only after numerous attempts to verbally deescalate the situation were unsuccessful.” His response did not dispute the detained men’s claim that they were protesting peacefully.

Cox said that “verbal [deescalation] attempts were successful in getting approximately ten detainees to become compliant.” He added, “however, to maintain orderly facility operations and protect the health and safety of all persons a brief calculated use of [pepper] spray was deployed against the group of detainees who refused to comply with directives from facility staff.”

For many people in ICE custody, the sense that neither deportation nor release is imminent is deepening a feeling of being trapped. Ernest said he’s been detained for 11 months, even though a judge ordered him removed from the country in December. Wilfred also said he’s been detained for months after signing a deportation order.

Ernest explained that he was healthy when he entered ICE custody but now suffers from depression and high blood pressure. He was infected with COVID-19 during an outbreak that started at Richwood in April, he said. Two guards at the jail died in late April and at least two people in ICE custody at Richwood were hospitalized with COVID-19. All 65 people who tested positive have now recovered or been released, according to ICE. (I wrote earlier this month about the fight to release one of those men.)

The two Cameroonians, along with people from countries including Bangladesh, Nepal, and Uganda, refused to leave the recreation yard on Monday as a way of protesting to demand their release, Wilfred said. He described guards at Richwood, a for-profit facility run by LaSalle Corrections under a contract with ICE, shaking cans of pepper spray as they approached him and other protesters. “When [the guards] were coming, we were sitting down,” he said, “because there was no violence.”

Wilfred added that he held up his hand to protect himself while guards sprayed him. He said he had bruising on his face and leg as a result of the force used to restrain him. He also told his attorney, Lara Nochomovitz, that guards had “climbed” onto his neck.

Asked about Wilfred’s claim that a guard placed a knee on his neck, Cox responded, “After employing OC spray facility staff physically restrained the detainees and took them for medical evaluation. The use of force was conducted in accordance with agency policy and reported to ICE HQ for review, which is standard practice.”

A Cuban man in another dorm at Richwood, who reported having been detained for more than a year, said that even one of the ICE deportation officers at Richwood told him he couldn’t understand why the agency is refusing to release some people there. Even detainees who want to be deported rather than stay in facilities where coronavirus is spreading have continued to spend months in detention, due to bureaucratic delays and because countries have been reticent to accept deportees from the United States, which has the world’s most coronavirus cases and deaths.

But the Cuban man, like many Richwood detainees I’ve spoken to, wondered whether ICE’s decision to hold people for such long periods of time was a scheme for enriching private prisons companies. “It’s like they have us kidnapped here,” he said, in Spanish. “That might sound a bit harsh, but it’s like being kidnapped.” He added, “It sometimes seems to us like they’re running a business here.”