A criminalist prepares DNA samples for analysis in a crime lab.Matt York/AP

CeCe Moore knew that she could find serial killers. But she wasn’t sure that she should.

By the time authorities in Sacramento, California, announced an arrest in the Golden State Killer case in April 2018, Moore had spent years uncovering family secrets for hire as a self-taught expert in DNA and genealogical research. Using consumer genetic tests, she reconstructed family trees for adoptees and helped the children of American soldiers in Vietnam identify their half-siblings in the US. She rediscovered the identity of a man with amnesia. And she went on TV—Dr. Oz and 20/20 and Finding Your Roots—spreading the gospel of genetic genealogy, the name for the investigative technique she and other “citizen scientists” had developed.

Law enforcement officials had long been asking Moore to apply genetic genealogy to crime scene DNA. Each time, she said no. “I just didn’t feel I could ethically do it,” she says. “I’ve encouraged thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands or more people to take consumer DNA tests. I didn’t want to then go and use their DNA in such a way that might seem like a betrayal.”

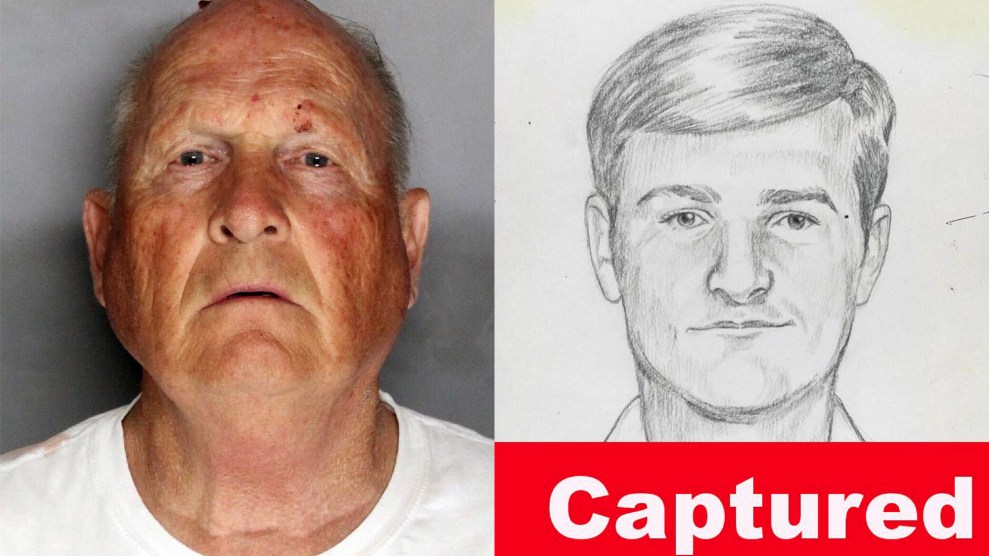

Then, police announced that they had identified a suspect in the decades-old serial rape and murder case with assistance from an amateur genetic sleuth using techniques like Moore’s. First, investigators asked the FBI to sequence crime scene DNA they believed came from the perpetrator. They uploaded the results to GEDmatch, a popular free database where anyone can share their DNA profile after taking a consumer test. After identifying distant cousins on GEDmatch, investigators used public records and social media to construct those cousins’ family trees, tracing the branches to a man the right age, in the right place, with the right amount of shared DNA: Joseph DeAngelo. When they compared a swab from his car door handle against DNA from the crime scenes, it matched. He’s now accused of at least 13 murders and dozens of rapes.

Details of the case soon plastered newspaper front-pages and international media outlets—igniting broad discussion over many of the same ethical concerns Moore had been struggling with. At the heart of the debate was how, without explicitly consenting to a police search, a single user of a consumer DNA test could unknowingly cast legal suspicion on hundreds of family members. “Three hundred people, most of whom you do not know and have probably never met, can illuminate your genetic information,” biologist Rori Rohlfs and bioethicist Stephanie Fullerton wrote in an op-ed last year in Leapsmag, a science magazine funded by Bayer. “There is nothing that you can do about it, no way to opt out.”

The arrest changed everything for Moore. While the public was mostly cheering the breakthrough, GEDmatch changed its privacy agreement to state clearly that law enforcement was using the database. That “opened the door” for Moore. Within days of DeAngelo’s arrest, she said yes to working a cold case. Moore identified her first suspect, she says, within two hours of receiving results on GEDmatch.

But while Moore has come to peace with her qualms over law enforcement using genetic genealogy, academics, legislators, and Washington bureaucrats are just now starting to grapple with the same issues. While that debate continues on, nearly a year after the Golden State Killer arrest provided a template for investigators all over the country, regulation governing how and when cops can use the technique is nonexistent. The result is a law enforcement free-for-all, with police and allies digging into consumer DNA databases with little law or policy to guide them.

Since Moore decided to go all-in on assisting police, the genetic genealogy slice of the forensic industry has grown rapidly. Shortly after the Golden State Killer arrest, Moore was hired to lead a team at Parabon NanoLabs, a biotech company known for creating forensic sketches based on DNA sequences. It has since emerged as the go-to contractor for police departments across the country hoping to crack cases with genetic genealogy. News of such arrests now breaks almost weekly: On February 15, in Alaska, state troopers announced that findings from Moore’s team helped them to identify and arrest a man for sexually assaulting and killing a fellow student at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks in 1993. On February 20, in Orange County, California, authorities announced that with Parabon’s help, they’d found and charged a man with the 1973 murder of an 11-year-old. As of mid-February, Moore estimated that her team has identified 36 suspects using crime scene DNA, including some individuals who were deceased. Three have pleaded guilty.

Other labs are now starting to get in on the game: The largest forensic DNA company in the US, Bode Technologies, announced last month it was launching its own team. Law enforcement officers are also increasingly looking for training from self-taught genetic genealogists, Moore says, and the FBI has started its own unit dedicated to the practice.

Meanwhile, the prospect of finding hits in public databases continues to grow, thanks to the mainstreaming of consumer DNA testing. More than 200,000 profiles have been added to GEDmatch since last May, Wired reported in December, bringing its total to about 1.2 million. On January 31, Family Tree DNA confirmed that it allows law enforcement to search its database of more than a million entries. Researchers recently told BuzzFeed that between those two services, police can now likely link almost all Americans with European heritage to at least a third cousin.

As genetic genealogy spreads, of course its risks do too. One fear is its potential to place innocent people under police suspicion. In her book Inside the Cell: The Dark Side of Forensic DNA, New York University law professor Erin Murphy warns that the practice of searching for genetic relatives could cast wide nets of suspicion over families, and lead cops to test a person’s DNA despite no independent evidence linking them to a crime. Victims could be pressured not to report crimes, she writes, “for fear of implicating their own relatives in other offenses.” And by examining family trees, police could expose secrets of people uninvolved in the crime in question, including infidelity, incest, and abandoned children.

Just consider that California investigators, before they arrested DeAngelo last year, collected DNA samples from at least two other men in connection with the Golden State Killer case, including a 73-year-old Oregon man in a nursing home whose daughter had uploaded her genetic profile to Ysearch.org. After police determined that the man had an uncommon genetic mutation they were looking for, the judge permitted authorities to obtain his DNA by force if necessary, according to the Los Angeles Times. And in a separate case in 2015, a partial match in an Ancestry.com-owned database led police to suspect a New Orleans filmmaker, Michael Usry, of a 1996 murder. In both cases, the men were ruled out as suspects after police compared their DNA samples to the crime scene using traditional DNA testing. But that confirmation process is far from bulletproof; years of investigations have revealed how contamination, mistakes, and fraud can lead to false DNA matches and wrongful convictions.

Skeptics have raised other concerns too. Steve Mercer, a Maryland defense attorney specializing in DNA and forensic science, told Bloomberg that police would inevitably want to apply genetic genealogy not just to rapes and murders, but also to minor crimes like trespassing. And computer scientists at the University of Washington published a working paper that outlines how criminals could manipulate investigators with fake or modified DNA profiles.

Legislatures, city councils, and attorneys general offices have all historically played a role in regulating the way police can use DNA to scrutinize families. Since the 2000s, amid advances in DNA technology, some states have debated the use of so-called “familial searches” in CODIS, the FBI’s national DNA indexing program, which contains profiles taken from convicted offenders, as well as people arrested for violent crimes or burglary. CODIS profiles consist of 20 genetic markers—significantly fewer than the hundreds of thousands of data points used in consumer testing and by genetic genealogists. They’re good for finding exact DNA matches but bad at locating even close relatives, the FBI has determined.

Nevertheless, a handful of states have decided to allow familial searches in CODIS since 2006, when then-FBI director Robert Mueller first authorized them. Some compromised; California and Virginia, for instance, opted to permit familial searches only in cases when all other investigative leads had been exhausted. Maryland and Washington, DC, went the other way, banning familial searches altogether, in part due to concerns that the overrepresentation of people of color in law enforcement DNA databases would amplify police suspicion of minority communities.

Earlier this year, Maryland looked like it might again be ground zero for DNA regulation. In January, Maryland Del. Charles Sydnor III introduced a bill that aimed to expand that prohibition on CODIS familial searches, banning police from using genetic genealogy entirely by preventing cops from searching any DNA database for relatives using crime scene genetic material. The bill would have been the first in the country to regulate genetic genealogy based on concerns about “genetic surveillance.” “Once people have given their DNA over, they give it over for their children, and children’s children,” Sydnor tells Mother Jones. “That’s somewhere I don’t think we want to go.”

But the law was broadly opposed by state law enforcement, and a Maryland rape-kit testing group also expressed “vehement opposition” to the bill, according to state Del. Jon Cardin. (Parabon CEO Steven Armentrout also testified against the bill in a hearing.) The bill died within weeks, though Sydnor says he is now planning a briefing for the Maryland House Judiciary Committee on the topic “for us all to learn a bit more” about it. “I think I’m probably far out there when it comes to some of these things,” he says. “But I know that this stuff is being used, and I don’t think people are really thinking about the implications.”

David Kaye, a law professor at Pennsylvania State University, suggests there’s a potential compromise before states completely ban cops from using genetic genealogy: Laws could prohibit police from using consumer tests’ more detailed genetic profile to look up medical information about a suspect. They could stop the release of sensitive family information like infidelity or adoption without a court order. Or they could limit its use to serious crimes, like sexual assault and homicide, and require police to exhaust other leads first, akin to some regulations on familial searches in CODIS.

At the national level, the Federal Trade Commission has been investigating the privacy practices of companies like Ancestry.com and 23andMe, and at least one consumer advocacy group has ramped up pressure on the FTC and Congress to specifically look at law enforcement’s role. (Weak privacy laws mean that even companies like Ancestry.com and 23andMe, which both say they resist law enforcement attempts to access user data, have to hand over at least some information if police get a warrant.) But so far, no agency has taken action.

The technique is still just “too new,” says Andrea Roth, director of the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology. “Arguably,” she adds, state-imposed limits on CODIS familial searching “should be a model” for future genetic genealogy regulations.

In lieu of state or federal laws or policies governing how cops can use the technique, the best hope for regulation is the court system. “When you think about what cops can do and what they can’t do, what guides them, it’s always going to be what the courts have already ruled on,” explains Chris Karakostas, a homicide investigator in Minneapolis who recently started using genetic genealogy to crack cold cases.

But so far, the courts have been silent. No police departments have yet been sued over their use of genetic genealogy. No judge has ruled on whether it violates the privacy rights of defendants, or DNA test consumers, or their families. None of the suspects identified using the technique have even faced trial. (It could be 10 years before the courts resolve DeAngelo’s case in California.)

“It’s like the Wild West,” says Kaye, who believes the courts would find that using genetic genealogy for crime-solving is probably legal under current laws. For one thing, previous Supreme Court rulings have treated DNA as no different than fingerprint evidence, which can be collected at will, even though DNA encodes more sensitive information and can be used to identify entire families. For another, it’s hard for defendants to argue that police invaded their privacy by testing blood or semen found at crime scenes. “The only thing we have is the Fourth Amendment,” Kaye says, “and it probably doesn’t give much protection here.”

Moore predicts that this year, a hundred cases will be solved with genetic genealogy—and that increasingly, they’ll include active cases along with cold ones. Nearly a year since her decision to start assisting police jumpstarted an industry, Moore says she no longer has ethical concerns about her work.

“In the case of adoptees, people have the right to know who they are. And in the case of these law enforcement cases, the families deserve answers,” she says. “There’s really no reason for serial killers and serial rapists to exist in the future.”