Lorin Eleni Gill/AP

London Breed officially became San Francisco’s first black female mayor Wednesday, surviving a bruising election and over a week of uncertainty after the polls closed, when Mark Leno conceded the race.

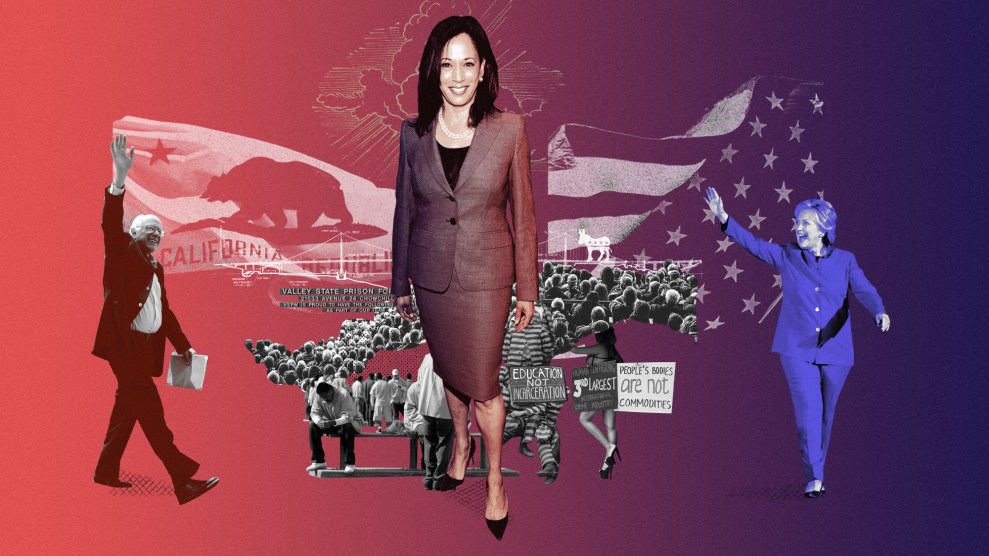

The victory makes Breed the latest in what can seem like a national wave of black women running for and winning—or at least progressing toward—public office. These women—think relative newcomers like Stacey Abrams and Lucy McBath, but also veterans like Rep. Maxine Waters and Sen. Kamala Harris—have risen from stalwart supporters of the Democratic Party to active participants and symbols of the resistance, a phenomenon that’s markedly heightened with President Donald Trump in office. They also largely enjoy the broad support, financial and otherwise, of the left. Breed, though, is not exactly of the same type, at least in ultra-liberal San Francisco, and she certainly has not ascended to the status of Liberal Darling.

In a state that’s deep blue, in a city of progressives, she’s considered a true moderate. But what exactly that means isn’t totally clear. In its endorsement of her back in April, the San Francisco Chronicle noted there wasn’t actually much of a difference between Breed and her opponents on policy issues; rather, she largely stood apart for “her willingness to listen to competing arguments and come up with adjustments that achieve a progressive ideal in a more workable and reasonable manner.”

So if it’s true that San Francisco politics could provide one blueprint for how the Democratic Party nationally could lean harder into its more progressive tendencies, then Breed’s election is also a cautionary tale of the gap that still exists between white progressives and black voters. The post-2016 Democratic soul-searching has seen the party focus its energy on down-ballot races with many unabashedly progressive platforms. But San Francisco’s mayoral election shows that the left is still working through its racial anxieties.

“As a progressive movement, if we ignore the role that race is playing among and in the context of this race, we’re missing the biggest lesson from 2016,” says Aimee Allison, president of Democracy in Color, a race and politics think tank. “The standard that they hold black women leaders to, especially given who’s in the White House and people in other positions of authority, is nonsensical. It’s so high…[and] it exposes the whole narrative about who’s progressive enough and who isn’t progressive.”

To understand Breed’s relationship to progressive politics, it helps to know how she grew up. Now 43, she was born in San Francisco and raised in the city’s Plaza East housing projects in the historically black Fillmore District by her grandmother. The badly neglected projects stretched across three city blocks, made up of several 11-story, peach-colored cement buildings less than a mile away from City Hall. Violence had become so endemic by the 1980s that the buildings earned the nickname among locals of “Outta Control Projects”—or OCP for short. In June 1981, 33 tourists reported being robbed in the area immediately surrounding Plaza East, which was so bad for the city’s tourist-friendly image that then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein personally apologized to one young woman who wound up in the hospital and then invited her to be a house guest while she recuperated.

Still, it was home to generations of mostly black San Francisco residents. Breed lived in one apartment with her grandmother, while an aunt lived with her family in another. “Poverty took so much from us, but never our sense of community, never our homes,” she later wrote in the San Francisco Examiner. “That pain came later.”

In 1996, the New York Times ran an exposé about the problems plaguing the Department of Housing and Urban Development nationally and focused on Plaza East. “The building isn’t livable,” one resident told the paper. “But at least we’ve got a roof over our heads.” Breed and her family, though, stood to lose even that when, later that year, the city announced its plans to demolish and rebuild Plaza East.

By this time, Breed had graduated from Galileo High School and was working toward a degree in political science at the University of California-Davis, so she thought she was well-versed in the ways of power to know where to turn to for help: the San Francisco Tenant’s Union, which had helped residents fight displacement since the 1970s. But she was turned away. “We don’t work with public housing residents,” she remembers being told.

For Breed, the encounter crystallized the blind spots of white progressives in San Francisco. (The encounter also grew into a mutual dislike; the Tenants Union is now a vocal opponent of Breed’s.) Too often, ambitious, egalitarian-sounding plans were rolled out by activist-politicians, who were almost always white and who had little interest in or connection to black residents in the city. And those black residents’ concerns often lived in a complex web of problems that defied easy solutions: A tenants’ union that was focused only on renters in market-rate apartments instead of the city’s poorest residents in public housing was one. Police abuse in poverty-stricken communities that still desperately relied on their protection was another.

These issues, perhaps more than anything, have come to define Breed’s political philosophy: The best people to fix a city’s problems are the ones who’ve lived them, not the ones who learned about them secondhand. And it’s a theme that’s defined her political rise. In 2016, when she faced a tough reelection to the Board of Supervisors against an upstart tenants’ rights attorney named Dean Preston, who routinely accused her of siding with developers over residents, she dug into the deep reserve of hostility most San Francisco natives have toward transplants and let it fly. “Unfortunately, I have experienced far too many Deans in my lifetime,” she told the San Francisco Chronicle. “People who come into our community and claim that they are going to be the savior of the community without understanding or ever hav[ing] lived the struggle of what the community has experienced.”

It’s characteristic straight talk from Breed, which has in turn has been called sassy and refreshing. She often doesn’t bother with niceties. And for that, her policies can be more complicated than liberal residents might be ready to handle. For instance, she endorses police carrying tasers instead of guns and led the push for an investigation into the police shooting of black resident Mario Woods, but she also encouraged parents to turn their kids into the police when they know they’re involved in violence. When longtime political reporter Tim Redmond criticized her voting record in 2016, he got an email from Breed, which he then published, accusing him of purposefully misrepresenting her positions. “You don’t even fact check your own bullshit ass blog,” it read. “As my grandmother used to say ‘I’m going to pray for you, cause you got the devil in you.'”

In many ways, Breed is the latest in a long line of black politicians who have seemingly been at odds with the city’s white progressives. In the 1960s, San Francisco’s high-poverty Tenderloin neighborhood was home to a majority of its LGBT community. In a historic move, a group of mainly poor white neighborhood activists began organizing to secure federal anti-poverty funds, which until then had been doled out mostly based on race. They ran into opposition from representatives of the city’s two major African American communities, who scoffed at the idea of diverting resources from their neglected neighborhoods. The white activists’ effort was ultimately successful, but only after they teamed up with Latino and Filipino residents who lived nearby, according to longtime activist and journalist Randy Shaw’s book, The Tenderloin: Sex, Crime and Resistance in the Heart of San Francisco.

Breed’s supporters still think the city’s progressive leaders are both willfully ignoring meaningful racial equity while maliciously blowing racist dog whistles when it suits them. Take, for instance, the contention that Breed is a pro-development moderate. “In a place like San Francisco, where Republicans aren’t in charge, to be called a moderate is a little laughable,” says Allison.

Making things more complicated for Breed is that the skepticism about her doesn’t fall strictly along racial lines. Black organizers on the more radical end of the political spectrum have also voiced misgivings, considering Breed to be too deeply enmeshed in the city’s problematic power structure. Breed has spent years cultivating relationships with longtime black power players, proving to some that while she touts her humble beginnings, she’s actually a consummate insider. She interned for the city’s first black mayor, Willie Brown, in the Office of Housing and Neighborhood Services. For years afterward, she was executive director of the African American Art and Culture Complex in the city’s Western Addition. She considers both Brown and Sen. Kamala Harris, who spent two terms as the city’s district attorney, personal mentors. When Breed was running for district supervisor in 2012, Harris gave a rousing endorsement speech, reminiscing about seeing her run around City Hall as a young volunteer. “We understand the need to have a daughter of this district represent this district,” Harris said.

Alicia Garza, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter who spent a decade organizing black residents against redevelopment plans in the city’s Bayview neighborhood, sees this and Breed’s voting record pushing new development projects as big concerns—which is why Garza supported mayoral candidate Jane Kim instead.

“As much as I love the idea of having a black woman in office, as much as I love the idea of this woman who grew up in the projects in Fillmore becoming the mayor in San Francisco,” she says, “I also really want a mayor who would govern in such a way that black people would be able to stay in their communities and not just communities that are ravaged by poverty and drugs, but communities that are thriving for black people.”

Breed hasn’t disqualified herself as that person in Garza’s view, but she has a lot of work to do.

If she couldn’t be “progressive enough,” Breed and her allies knew she could be San Francisco enough. Throughout the 2018 mayoral campaign, Breed and her allies skillfully deployed her personal narrative as a political asset: She went to the city’s public schools, so she’s deeply invested in fixing them. She grew up in poverty, so she’s uniquely equipped to understand issues like homelessness. Her sister died of a drug overdose, so she understands the need to tackle addiction. Her brother is currently in prison, so she knows the unique personal costs of crime and incarceration. For voters, that strategy worked, pushing her over the top in nearly every major district in San Francisco, while also earning enough second-place votes to beat out Leno in California’s controversial ranked-choice voting system.

This map should really show who the majority wanted to be mayor. Blue wave! pic.twitter.com/kl0PPry8fE

— SFHilltopStay (@SuperhostSF) June 12, 2018

Breed’s critics underestimated how much her presence means against the exodus of working- and middle-class black residents from the city. San Francisco’s black population has declined rapidly over the past two decades; African Americans now make up less than 3 percent of the city’s total population. The city has the second-largest gap between rich and poor of any major city in the country, and as the incomes of other races have inched upward, black people’s wages have remained stagnant or declined altogether. Those facts made her elevation to acting mayor, after the sudden death of former mayor Ed Lee in late 2017, all the more historic. She was praised nationally as the first black woman to become the city’s mayor, but in a twist, she had the mayorship stripped from her after members of the Board of Supervisors worried that her workload would be too big and that she would go into the mayor’s race with an unfair advantage.

“You talk to black people who are voters in San Francisco, and you talk to black women in the Bay who are looking at this race, and there’s a widespread, pretty disgusted sentiment about the way she’s perceived to have been treated,” says Allison.

Just take the way Leno, who’s white, and Kim, who’s Korean American, teamed up. The two deeply progressive supervisors, who were Breed’s main challengers in the mayoral race, tried to game the ranked-choice voting system by asking voters to rank the two of them as their top choices and explicitly denouncing Breed. They and other Breed critics routinely attacked her for being a puppet of corporate interests—specifically of Ron Conway, the billionaire angel investor, who contributed generously to Breed’s campaign and the political action committees that support her. “You should pick out next mayor, not the billionaires,” they said in one joint ad.

Proud to stand together with @janekim — and proud to stand against special-interest Super PAC spending.

When you vote, vote for Mark Leno (#1) and Jane Kim (#2) because we agree: the City belongs to us, not the billionaires. pic.twitter.com/GKe8ie9GM2

— Mark Leno (@MarkLeno) May 10, 2018

The move was perceived as racially coded by many Breed supporters, and it backfired. “I am nobody’s slave—no white man millionaire slave,” Breed said in one campaign speech. “So let’s set the record straight: Slavery is over. Slavery is over. It’s time for a new day in the city and county of San Francisco. Do not fear black leadership.”

For many black women watching the race, the refrain struck a chord. “She’s not the evil archetype that people have tried to construct her to be,” says Garza. “She’s actually not beholden to tech interests; it’s the fact that she’s not beholden to anyone that makes her dangerous.” She added, “And that can be a good dangerous or a bad dangerous, but it really depends on the context.”

Seen from one angle, Breed’s relative moderateness is a refreshing sign of black political diversity. Not every local politician is looking to completely upend the system. But nationally, her election sheds light on the problematic idea that black women running for office be bestowed with a progressive “savior” status.

“I think what we saw in this election is that there is a deep disconnect between black communities and the progressive movement in San Francisco,” says Garza. “And until that gets bridged, we’re going to continue to have to make these kinds of choices and be agonized by the fact that while it would be amazing to have a first, we also want to make sure that it’s not just about having a first, but having a first that shares our vision for equity and justice.”