This article was published in partnership with ProPublica Illinois.

By last summer, Laqueanda Reneau felt like she had finally gotten her life on track.

A single mother who had gotten pregnant in high school, she supported her family with a series of jobs at coffee shops, restaurants, and clothing stores until she landed a position she loved as a community organizer on Chicago’s West Side. At the same time, she was working her way toward a degree in public health at DePaul University.

But one large barrier stood in her way: $6,700 in unpaid tickets, late fines, and impound fees.

She had begun racking up the ticket debt five years earlier, in 2012, after a neighbor who saw her riding the bus late at night with her infant son sold her her first car, a used Toyota Camry, for a few hundred dollars. She was grateful for the shorter commute to work but unprepared for the extra costs of owning a car in Chicago.

That year alone, Reneau got 15 tickets, including seven $200 citations for not having a city sticker. Later, she received a dozen tickets for license plate violations on another used car that couldn’t pass emissions testing, a state requirement to renew her plates.

“Those tickets have followed me until this freaking day,” said Reneau, who is 25.

Because of the unpaid tickets, the city garnished her state tax refunds. Her car was impounded and she couldn’t pay for its release. Her driver’s license was suspended. Unable to come up with $1,000 to enter a city payment plan, Reneau did what thousands of Chicago drivers do each year: She turned to Chapter 13 bankruptcy and its promise of debt forgiveness.

“I know I’m putting a Band-Aid on the problem,” she said. “But right now, my immediate need is to get a car so I can get to work and get my son to school.”

For Chicago’s working poor, and particularly for African Americans, a single unpaid parking or automated traffic camera ticket can quickly spiral out of control and threaten their livelihoods. Bankruptcy offers a temporary reprieve, giving these motorists the chance to resume driving without fear of getting pulled over or losing their vehicles to the city pound.

The problem has gotten worse over the past decade, ProPublica Illinois found in an analysis of bankruptcies filed in the Northern District of Illinois, which includes Chicago and its suburbs.

In 2007, an estimated 1,000 Chapter 13 bankruptcies included debts to the city, usually for unpaid tickets, with the median amount claimed around $1,500 per case. By last year, the number of cases surpassed 10,000, with the typical debt to the city around $3,900. Though the numbers of tickets issued did not rise during that time, the city increased the costs of fines, expanded its traffic camera program, and sought more license suspensions.

The result: more debt due to tickets.

Legal experts say what’s happening in Chicago’s bankruptcy courts is unique. Parking, traffic, and vehicle compliance tickets prompt so many bankruptcies the court here leads the nation in Chapter 13 filings.

It’s a problem fueled both by the city’s increasingly aggressive ticketing to boost revenue—tickets brought in nearly $264 million in 2016, or about 7 percent of the city’s $3.6 billion operating budget—and a handful of law firms that pitch bankruptcy protection as a cheap solution to drivers’ woes.

Advocates for the poor say the bankruptcy statistics are symptoms of a broken city system that unfairly burdens those least able to afford tickets, much less late fees and other penalties. Motorists with crushing ticket debt who want to get back behind the wheel are stuck choosing between a city payment plan they often can’t afford or a bankruptcy plan that’s cheaper to enter but likely to fail.

When bankruptcy cases are dismissed, drivers risk losing their cars and licenses again, setting up a cycle of more debt and potentially more bankruptcies.

“If you’re a city government that has a policy of basically balancing the budget by issuing huge numbers of traffic tickets, you have to expect this response,” said John Rao, an attorney who specializes in bankruptcy at the nonprofit National Consumer Law Center. “There’s obviously a market for consumers who are in need of relief, and while it’s not the perfect form of relief, the other options aren’t that great either.”

Debt That Lasts Forever

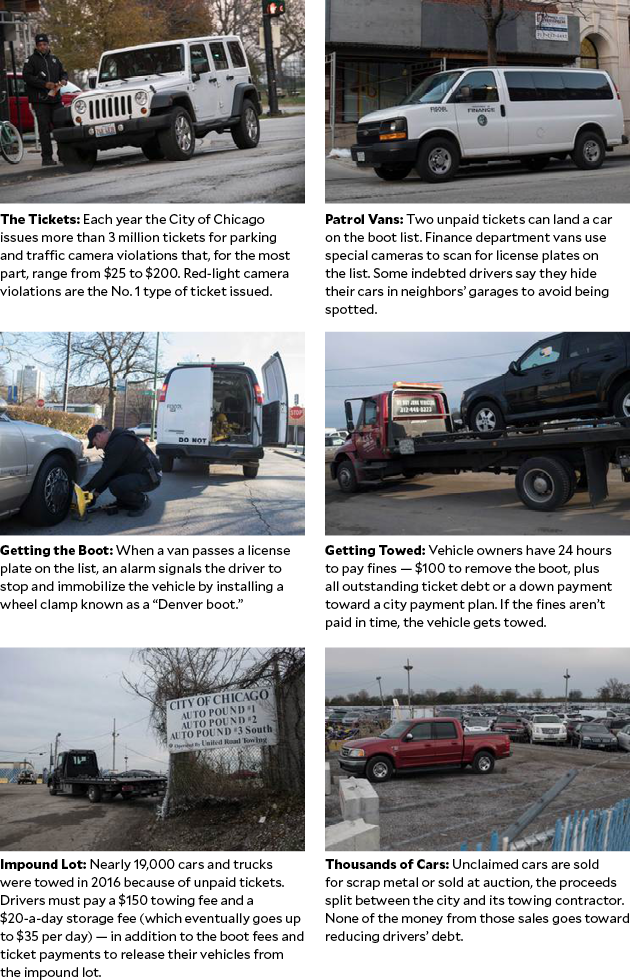

Each year, the City of Chicago issues more than 3 million tickets for a wide range of parking, vehicle compliance, and automated traffic camera violations, from $25 citations for broken headlights to $250 tickets for parking in a disabled zone.

The overall numbers of tickets had been on the decline until 2013, when the city’s first speed cameras came online. More citations are issued here, per adult, than in Los Angeles or New York City.

Ticket debt piles up disproportionately in the city’s low-income, mostly black neighborhoods. Eight of the 10 ZIP codes with the most accumulated ticket debt per adult are majority black, according to a ProPublica Illinois analysis of ticket data since 2007 and figures from the US Census.

Those neighborhoods account for 40 percent of all debt, though they account for only 22 percent of all the tickets issued in the city over the past decade—suggesting how the debt burdens the poor.

Edward Morrison, a law professor and economist at Columbia Law School who has studied the ties between ticket debt and bankruptcy in Chicago, said low-income, African American households are more affected by ticket debt because they have less money to pay tickets even before debt mounts.

Tickets for red-light camera violations—issued when drivers turn illegally or run through a red light—make up the greatest number of all citations.

But compliance tickets for lacking a city sticker or having expired plates—the kinds of citations Reneau got repeatedly in her first years of owning a car—are disproportionately involved in bankruptcy cases.

Indeed, sticker violations were the largest source of ticket debt in Chicago. They accounted for about 19 percent of citations connected to bankruptcy cases but only 4 percent of those marked paid. City stickers, which must be purchased annually, cost about $87 for most passenger vehicles.

“So if you don’t have the money to pay the city sticker and you get a ticket, what makes you think you’re going to have the money to pay the ticket?” said Salvador J. Lopez, a bankruptcy attorney with the consumer law firm Robson & Lopez LLC. “It’s very easy for the average person to say [filing for bankruptcy over tickets] is being irresponsible, but let’s take a look at what’s causing people to rack up these tickets.”

The city mails vehicle owners multiple notices to give them time to pay or contest tickets before fines double, get sent to collections, or land a car on a list to be booted. Once debt accumulates, it can last forever because there’s no statute of limitations for unpaid tickets in Illinois. Chicago motorists owe $1.45 billion in ticket debt dating to September 1990.

By comparison, ticket debt in Los Angeles, where the statute of limitations is five years, is $21 million. In New York City, with a statute of limitations of eight years, ticket debt totals $238 million, according to officials.

In addition to booting and impounding vehicles, the city has another weapon at its disposal: It can move to suspend licenses after drivers accumulate 10 unpaid parking tickets or five unpaid traffic camera tickets.

In 2016, Chicago asked the state to suspend licenses of more than 21,000 drivers, up threefold since 2010, according to the city’s finance department. One reason for the increase: In 2013, the city started counting such compliance violations as not having a city sticker against drivers for license suspensions.

Meanwhile, “anti-scofflaw” rules prevent those with unpaid tickets or other debts to the city from accessing contracts, licenses, and even grants for low-income homeowners who want to replace their home furnaces. Taxi and ride-share drivers can’t work in the city if they have ticket debt.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who has faced one budget crisis after another since coming into office in 2011, made cracking down on “scofflaws” on the municipal payroll an early priority.

“If you owe a parking ticket, you owe a bill, you have to pay. The free ride is over for everybody,” Emanuel said in 2011. “I want people to know that the whole city’s watching.”

Municipal jobs—from driving a bus to teaching in a classroom—have long been off-limits to drivers with ticket debt, unless they’re on a city payment plan or in bankruptcy. Tracy Occomy Crowder, an organizer with Community Organizing and Family Issues, a nonprofit that works mostly with low-income women of color, said her group became interested in the issue after learning that a longtime parent leader said she couldn’t get a job as a recess monitor at her son’s elementary school because of unpaid tickets.

“It seems like the city is shooting itself in the foot,” Occomy Crowder said. “How can people pay the city if they can’t get jobs?”

In January, COFI issued a series of recommendations to the city on how to make ticket debt less punishing for low-income families as part of the release of a report called “Stopping the Debt Spiral.” Among them: make it easier for people with ticket debt to get municipal jobs and licenses; make payment plans more accessible; and waive late penalties on ticket debt.

COFI is also asking the city to create a task force modeled after one in San Francisco studying how municipal fines and fees disparately impact low-income people of color. This issue has gained national attention since the release of a 2015 US Department of Justice report that highlighted, in part, how the criminal justice and court systems in Ferguson, Missouri, relied on excessive fines and fees to generate revenue.

Alex Kornya, an assistant litigation director of Iowa Legal Aid who has studied the impact of court debt on the poor around the country, said what’s happening in Chicago is part of a broader trend of local governments using “systems that were made to ensure the public safety as revenue generators.”

“You’ve introduced this perverse economic incentive which has flipped the system upside down,” he said.

No Good Option

Laqueanda Reneau is a petite woman with a steady gaze. She speaks guardedly, aware from experience that she may be judged by her appearance and circumstances: a single, young black mother who can barely make ends meet.

“I know what my stance is in this world,” she said.

She can relate to the residents she works with in her job as a community organizer in the neighborhood where she grew up.

“I want to work on something that has to do with inequities, making sure that communities that need resources are able to get to those resources, whether it’s health or economic development,” she said. “I just want to make sure people have the opportunities to get—what do they say?—the American Dream.”

Her own dream—to join the Navy, go to college, and become a nurse—got derailed as a high school senior, when she got pregnant. Not long after she had her son, she left her parents’ home.

She acknowledges getting one ticket after another and not paying them. She needed the money she earned, she said, to pay rent, buy food, and put gas in her car. The tickets were not a priority for her survival, and she said she wasn’t aware of the potential consequences.

After surrendering her car to the city’s impound lot and losing her license because of unpaid tickets, Reneau studied her options. At the time, she and her then five-year-old son were living in a room they rented in a house with another family in South Holland, in the Far South suburbs. Their daily commute on public transportation was draining—for both of them.

Each morning, Reneau took a commuter train, then a bus to drop off her son at school on Chicago’s South Side. Then she took two subway trains to her job as an organizer for a community group with offices on the city’s North and West sides. After work, she rode another subway train or a bus to classes at DePaul. Then she headed home.

“He’s not going to bed until 11 p.m., then we have to get up at 6 a.m., and he’s tired in the morning,” Reneau said. “He hasn’t got his full rest. I realized how much of a chain reaction that is.”

Laqueanda Reneau poses on the street outside her home in Calumet Park, January 1, 2017.

Marc Monaghan for ProPublica Illinois

Some days she would borrow a friend’s car and drive illegally to cut down the travel time. But that made her anxious, especially after she got pulled over one night. Luckily, she said, the officer let her off with a warning after seeing her son in the back seat.

She qualified for the city’s hardship plan, which requires a down payment of $1,000 or 25 percent toward total ticket debt, whichever is lower. But she didn’t have the money. Reneau considered signing up for a city payment plan to recover her driver’s license and get another car. Of the $6,700 she owed the city—for a range of parking tickets, sticker violations, and camera infractions—less than half was for the original tickets; the rest was late penalties, 22 percent collection fees, impound fees, and even a $20 fee for the cost of suspending her license.

And even if she could have afforded it, Reneau doubted a city payment plan was best for her. She’d tried plans in the past but was unable to keep up with the required monthly payments. Each time she defaulted, she incurred a new $100 penalty.

“You ever try to call the city and ask for an extension, like you might do for a light bill?” she asked. “Other places, you can get an extension. But not with the city.”

Then one day she heard a catchy jingle on the radio for the Semrad Law Firm, which also calls itself DebtStoppers. It handles more ticket-related Chapter 13 cases than any other firm in the Northern District of Illinois, according to a ProPublica Illinois analysis of case data.

“I still remember the song. I find myself singing it,” Reneau said. “One of the first things they say is about…how you can get your license back. About the zero dollars down.”

Filing for Chapter 13 bankruptcy, she soon learned, was cheaper than getting on a city payment plan.

‘Is That a Band-Aid?’

There are two main types of consumer bankruptcy in the US Chapter 7. Filing under Chapter 7 can take just a few months and requires the liquidation of assets, although most filers do not have enough to clear a legal threshold that requires them to give anything up. Almost every Chapter 7 bankruptcy results in debt forgiveness.

Under Chapter 13, debtors get to hold onto their assets, like a home or car. But in Chapter 13, debtors have to apply their disposable income each month toward payments to creditors for up to five years. Only when a plan is completed will the rest of the debt be discharged, which is often difficult for poor people to manage.

Last fall, ProPublica reported that black debtors across the country disproportionately file under Chapter 13, when compared with whites. It’s a trend that’s particularly evident in Southern cities like Memphis because of the sheer volume of cases. There, debtors choose Chapter 13 because it’s cheaper at the outset, but they wind up paying thousands of dollars more in legal fees.

It’s a similar story in Chicago, where larger firms can offer to file a Chapter 13 case for zero down and charge $4,000 in legal fees as part of the required monthly payments. Chapter 7 cases, meanwhile, typically cost about $1,000, often with the debtor required to pay the money up front.

But there’s a more practical reason to file under Chapter 13: If you have ticket debt, unpaid tickets can be discharged under Chapter 13 but not under Chapter 7.

Reneau’s debt, for example, is almost entirely tickets. Her only other debt, according to her bankruptcy filing, is a few hundred dollars in credit cards, plus about $12,600 in student loans. Her student loans are in deferment and, in general, cannot be forgiven in bankruptcy.

FROM TICKETS TO THE TOW YARD

One reason so many Chicago drivers file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy over unpaid tickets is to protect their vehicles from the city impound lot. The city sends drivers multiple notices before fines double, go to collections, or land a car on the boot list. (Photos by Marc Monaghan for ProPublica.)

The immediate benefit of bankruptcy is time, thanks to a legal reprieve known as an “automatic stay.” This protection allows drivers to lift license suspensions tied to some kinds of debt and keep their vehicles off the boot list for as long as their bankruptcy case is active.

But bankruptcy is not a long-term solution for these debtors, who are poorer and disproportionately black and have fewer assets when compared with other people who file for bankruptcy under Chapter 13.

ProPublica Illinois analyzed the outcomes of a sample of almost 1,000 Chapter 13 cases filed in 2010, and found that fewer than a quarter that included unpaid ticket debt ended successfully. By contrast, cases without tickets were more likely to end successfully; according to the analysis, about half ended with debt relief.

Patrick Semrad, managing partner of DebtStoppers, acknowledged most Chapter 13 bankruptcies involving ticket debt get dismissed before drivers get a discharge. But he doesn’t think that necessarily makes them failures.

“For people with Chapter 13s, it’s not as fast or as clean [as Chapter 7 bankruptcy], but they’re able to get things like their car right away, or stop a foreclosure, or get their license back, or keep a job,” he said. “And so it’s not just about the debt. If someone is able to keep a job for a year or two years, is that a Band-Aid? I don’t think so.”

A New Tactic

Over the years, city officials have looked for ways to stem the flood of bankruptcies involving ticket debt. Because drivers in bankruptcy pay creditors such as the city pennies on the dollar, and because so many of their cases end in failure, the city recovers little from them. Of course, when bankruptcies are dismissed, the city and its debt collectors can go after drivers, their licenses, and vehicles once again.

City officials were especially frustrated by what, by all accounts, was an only-in-Chicago phenomenon: Motorists were filing for bankruptcy in droves to get impounded cars released without paying any impound fees or underlying ticket debt. To the city, what’s happened in bankruptcy court has been an abuse of the system: Drivers were ignoring tickets they lawfully deserved and then filing for bankruptcy to avoid paying what they owed. Meanwhile, attorneys were profiting off the cases even when the drivers got no debt relief.

The impound-to-bankruptcy phenomenon started in 2009, when a federal appellate court ruling extended the automatic stay to repossessed vehicles. Attorneys at DebtStoppers—which had filed the initial case—soon realized the ruling could also apply to cars and trucks impounded by the city because of unpaid tickets.

Racheal White stands in the middle of the 8100 block of South Shore Drive near her home.

Marc Monaghan for ProPublica

“We didn’t know this means we’re going to get all these parking ticket cases, but we knew anybody who was holding a car was now going to return the car immediately,” Semrad said. “And we enforced it vigorously.”

In 2016, an estimated 3,770 impounded vehicles were returned to drivers in bankruptcy. That represented more than a third of all Chapter 13 cases filed that year involving Chicago ticket debt.

“It was a pretty big nightmare for us,” said David Holtkamp, a senior corporation counsel for the city who oversees bankruptcy matters. “People were filing these cases they had no intention of completing. They’d file it, get the car out, and then the case would ultimately get dismissed…And then they would file again.”

Last year, the city unveiled a new legal strategy to deter these kinds of bankruptcies. It now claims liens on impounded vehicles, which allows the city to hold onto them until the underlying ticket debt is recognized as a secured claim in bankruptcy court—meaning it will get paid out in full during a bankruptcy payment plan.

The tactic, yet another move in what seems like a cat-and-mouse game between the city and indebted drivers, has been upheld by some bankruptcy judges but is being appealed by motorists and their lawyers.

City officials say the liens aren’t just about the city’s bottom line; they say it’s also a consumer protection issue, a way to save drivers from bankruptcies that are likely to get dismissed without debt relief. Instead of paying a bankruptcy lawyer, city officials say, drivers should enter into payment plans with the city where every dollar goes directly toward outstanding debt.

In a way, Racheal White’s experiences with bankruptcy help illustrate this.

A single mother of two teenage boys, White moved reluctantly to the South Shore neighborhood a few years ago when she could no longer afford rent in the suburbs. Almost immediately, she started accumulating tickets, many of them speed camera violations.

White depended on her car, which she lovingly calls “Rosie,” to get to a range of contract work across the metro area, including her main job as a dental assistant, a gig handing out product samples at stores and events, and an acting job as a hospital patient for medical students.

Watch ProPublica’s video on ticket debt in Chicago:

White, 35, couldn’t afford to pay the tickets, and eventually her car got on the city’s boot list. She filed for Chapter 13 bankruptcy in 2016 to get a grip on her finances, and also to protect her car.

“Bankruptcy gives you a nest, like a covering,” she said. “It allows you to breathe so you can find a way to get yourself out of a hole, to not worry about having your license suspended or getting your car repossessed or your car booted.”

But less than a year later, her bankruptcy case fell apart. The dentist office where she worked cut back her hours, and she couldn’t afford to keep up with her payments. Her case was dismissed last fall.

She had made eight payments totaling $2,275, according to a final report issued by the Chapter 13 trustee who administered the case. More than $1,900 went to legal fees. Another $105 went to cover the trustee’s expenses. And $243 went toward her car loan—most of it for interest. Not a dime went to her unsecured debts, including the unpaid Chicago tickets.

Within weeks of her case getting dismissed, White’s Nissan went back on the city’s boot list and was impounded. White borrowed money from her mother to get on a city payment plan and get her car back.

Then she filed for bankruptcy again.

On Borrowed Time

In February, less than eight months after she filed for bankruptcy, Laqueanda Reneau told her lawyer to file the documents to dismiss her case. She had been making her bankruptcy payments on time, with $175 garnished from her paychecks each month. But as tax season approached, it dawned on her that she’d also have to hand over most of the $5,000 to $6,000 she said she expects to receive in her federal tax refund, which is considered income and must be taken into account in bankruptcy payment plans.

Reneau wasn’t willing to do that. She typically saves her tax refunds to deal with emergencies and “immediate needs that come up…throughout the whole year.”

Last year, she used $2,300 from her refund to buy a 2003 Kia Sorento. This year, Reneau wants to move into her own apartment in the city with her son. She plans to set aside enough money for the security deposit, rent, furnishings, and basic household items like plates.

When her case is officially dismissed, she knows she’ll be on borrowed time before the city moves to suspend her license and puts her car on the boot list again. She hopes to get on a city payment plan before that happens.

David Eads contributed to this report.