Ulysses Munoz/ZUMA

This story originally appeared on ProPublica and was published in partnership with New York magazine.

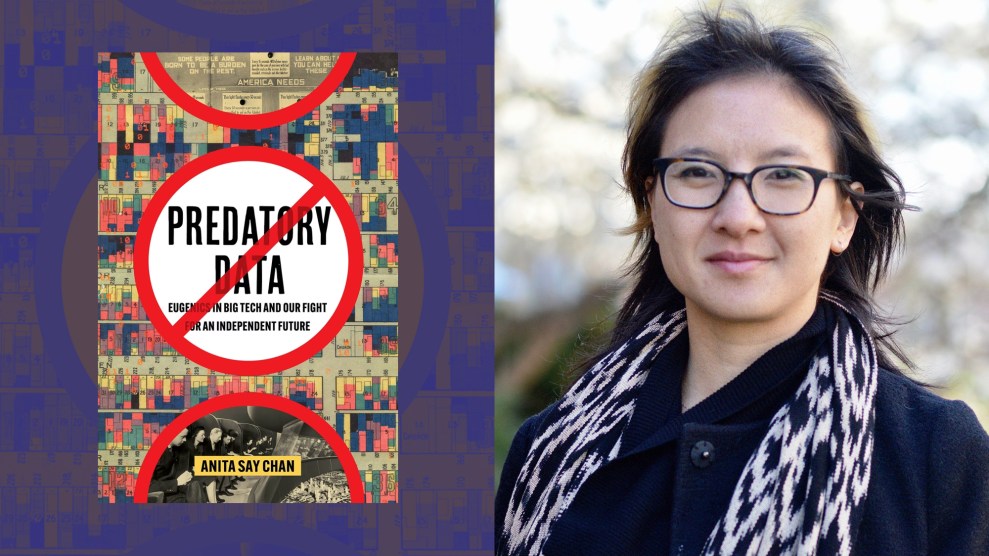

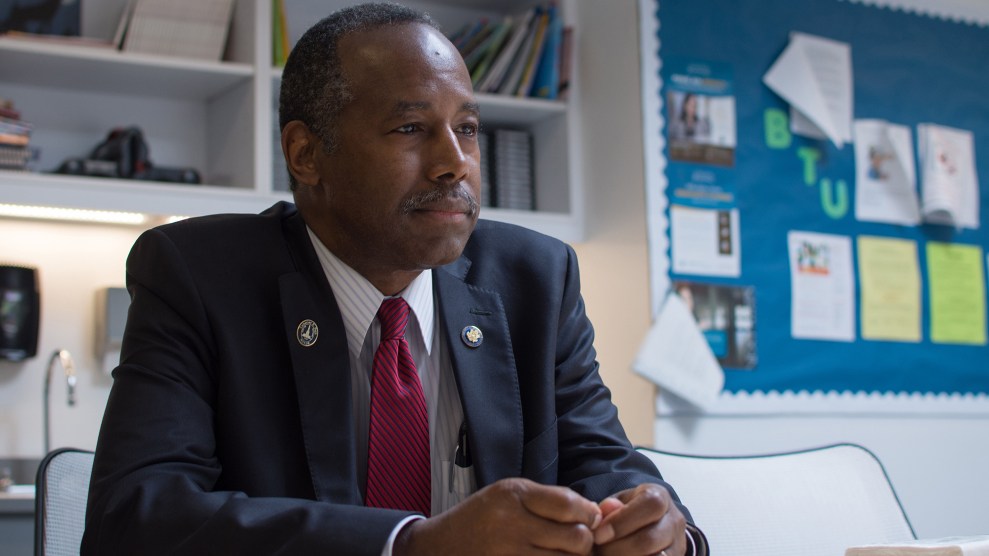

In mid-May, Steve Preston, who served as the secretary of housing and urban development in the final two years of the George W. Bush administration, organized a dinner at the Metropolitan Club in Washington, D.C., for the new chief of that department, Ben Carson, and five other former secretaries whose joint tenure stretched all the way back to Gerald Ford. It was an event with no recent precedent within the department, and it had the distinct feel of an intervention.

HUD has long been something of an overlooked stepchild within the federal government. Founded in 1965 in a burst of Great Society resolve to confront the “urban crisis,” it has seen its manpower slide by more than half since the Reagan Revolution. (The HUD headquarters is now so eerily underpopulated that it can’t even support a cafeteria; it sits vacant on the first floor.) But HUD still serves a function that millions of low-income Americans depend on—it funds 3,300 public-housing authorities with 1.2 million units and also the Section 8 rental-voucher program, which serves more than 2 million families; it has subsidized tens of millions of mortgages via the Federal Housing Administration; and, through various block grants, it funds an array of community uplift initiatives. It is the Ur-government agency, quietly seeking to address social problems in struggling areas that the private sector can’t or won’t solve, a mission that has become especially pressing amid a growing housing affordability crisis in many major cities.

Despite its Democratic roots, Republican administrations have historically assumed stewardship over HUD with varying degrees of enthusiasm—among the department’s more notable secretaries were Republicans George Romney and Jack Kemp, the idiosyncratic champion of supply-side economics and inner-city renewal.

Now, however, HUD faced an existential crisis. The new president’s then-chief strategist, Steve Bannon, had called in February for the “deconstruction of the administrative state.” It was not hard to guess that, for a White House that swept to power on a wave of racially tinged rural resentment and anti-welfare sentiment, high on the demolition list might be a department with “urban” in its name. The administration’s preliminary budget outline had already signaled deep cuts for HUD. And Donald Trump had chosen to lead the department someone with zero experience in government or social policy—the nominee whose unsuitability most mirrored Trump’s lack of preparation to run the country.

This prospect was causing alarm even among HUD’s former Republican leaders. At the Metropolitan Club, George W. Bush’s second secretary, Alphonso Jackson, warned Carson against cutting further into HUD’s manpower. (Many regional offices have shuttered in recent years.) Carla Hills, who ran the department under President Ford, put in a plug for the Community Development Block Grant program, noting that Ford had created it in 1974 precisely in order to give local governments more leeway over how to spend federal assistance.

The tone was collegial, built on the hopeful assumption that Carson wanted to do right by the department. “We were trying to be supportive,” Henry Cisneros, from the Clinton administration, told me. But it was hard for the ex-secretaries to get a read on Carson’s plans, not least because the whisper-voiced retired pediatric neurosurgeon was being overshadowed by an eighth person at the table: his wife, Candy. An energetic former real-estate agent who is an accomplished violinist and has co-authored four books with her husband, she had been spending far more time inside the department’s headquarters at L’Enfant Plaza than anyone could recall a secretary’s spouse doing in the past, only one of many oddities that HUD employees were encountering in the Trump era. She’d even taken the mic before Carson made his introductory speech to the department. “We’re really excited about working with—” She broke off, as if detecting the puzzlement of the audience. “Well, he’s really.”

The story of the Trump administration has been dominated by the Russia investigations, the Obamacare repeal morass, and cataclysmic internecine warfare. But there is a whole other side to Trump’s takeover of Washington: What happens to the government itself, and all it is tasked with doing, when it is placed under the command of the Chaos President? HUD has emerged as the perfect distillation of the right’s antipathy to governing. If the great radical conservative dream was, in Grover Norquist’s famous words, to “drown government in a bathtub,” then this was what the final gasps of one department might look like.

Nov. 9 brought open weeping in the halls of HUD headquarters, a Brutalist arc at L’Enfant Plaza that resembles a giant concrete honeycomb. Washington was Hillary country, but HUD employees had particular cause for agita. For years, the department had suffered low morale, and there was the perception, not entirely unjustified, that it was prone to episodes of self-dealing and corruption—most recently under Jackson, who was scrutinized for awarding HUD projects to companies run by his friends. But the department had experienced a rejuvenation in the Obama era, with morale rebounding under the leadership of his first secretary, Shaun Donovan, an ambitious, politically savvy housing administrator from New York. While it faced postrecession budget austerity—with its ranks dropping well below 8,000, from more than 16,000 decades earlier—the department made homelessness reduction a priority. Under Donovan’s successor, Julián Castro, the former mayor of San Antonio, HUD embarked on a major initiative to address residential segregation by requiring cities and suburbs to do more to live up to the edicts of the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Before the election, Hillary Clinton’s campaign sent over a large team of policy experts to study up on HUD and prepare to take the baton on these efforts. The Trump campaign sent one person. “And everyone was joking, ‘Well, he’ll be gone on November 9,'” one staffer told me.

So the stricken employees were slightly relieved when Trump’s operation announced a five-person “landing team” for HUD that included Jimmy Kemp, son of Jack. “There may be hope for us after all,” a veteran staffer in one local HUD office told his colleagues. The semblance of normalcy was short-lived. In late November, word got out that Trump’s choice to run HUD was Carson. To Twitter wags, the selection was comical in its stereotyping: Of course Trump would assign the only African American in his Cabinet to the “urban” department. But to many HUD employees, the selection of so ill-qualified a leader felt like an insult. “People feel disrespected. They see Carson and think, I’ve been in housing policy for 20 or 30 years, and if I walked away, I would never expect to get hired as a nurse,” said one staffer at a branch office, who, like most employees I spoke with, requested anonymity to guard against retribution.

Carson himself had some qualms about running HUD. His close friend Armstrong Williams, a conservative commentator who was exposed for receiving payments from George W. Bush’s administration to tout Bush’s education policies on air, told The Hill in November that Carson had reservations about such a job. “Dr. Carson feels he has no government experience; he’s never run a federal agency,” Williams said. “The last thing he would want to do was take a position that could cripple the presidency.” Williams later said his remark had been misconstrued, but Shermichael Singleton, a young political operative who worked for Williams and became a top aide on Carson’s campaign, told me that Carson’s ambivalence was real. Trump’s offer, Singleton said, had provoked deep questions for Carson about his life’s purpose. “It was, ‘Should I do this? What does it all mean?'”

In the end, Singleton said, Carson accepted out of a sense of duty that came from having risen to success from humble origins: raised by a single mother, a housekeeper, in Detroit. “He’s someone born in an environment where the odds were clearly stacked against him, and he believes by personal experience that he could do a lot of good for others.” Kemp agreed. Carson accepted, he said, “because he wanted to do something about poverty.” If anything, Kemp said, Carson felt more suited to the HUD job than he would to a health policy one. “Being surgeon general or secretary of [health and human services], I don’t think he was fully equipped to do that, having been a neurosurgeon,” Kemp said. In other words, Carson knew how little he knew about health policy, an awareness he lacked when it came to social policy. “He thought with HUD, ‘It’s so clear that our approach to poverty has not been completely successful and we can do better, and I think I have some ideas that can be applied,'” Kemp said.

Underlying this rationale were two related convictions. One was the standard conservative bias against expertise and bureaucracy, according to which experts lacked the “common sense” that an outsider from the private sector could provide—a conviction shared, of course, by the man who nominated Carson for the job. The other was a more particular conviction that he, Carson, possessed extra doses of such common sense by virtue of his biography.

First, though, Carson had to survive his confirmation hearing. The prepping was intense. His top handler was Scott Keller, a longtime lobbyist who had served as chief of staff under Jackson and, in that role, become embroiled in the contracting scandals. Keller’s pupil was attentive, and his performance at the January hearing before the Senate Banking Committee was judged a relative success by the press, punctuated by Carson’s disarming remark that the panel’s top Democrat, Sherrod Brown, reminded him of Columbo. Carson’s family and closest aides took him to the Monocle, the lobbyist hangout on the Hill, to celebrate.

As Carson awaited confirmation, though, a leadership cadre was already entrenching itself in the administrative offices on the 10th floor of HUD. The five-person landing team had given way in January to a larger “beachhead” team. This was a more eyebrow-raising group. Its few alums from past GOP administrations were outnumbered by Trump loyalists such as Barbara Gruson, a Manhattan real-estate broker who’d worked for the campaign; Victoria Barton, the campaign’s “student and millennial outreach coordinator”; and Lynne Patton, who had worked for the Trumps as an event planner.

The most influential of the new bunch, it would quickly emerge, was Maren Kasper. Little-known in housing policy circles, and in her mid-30s, Kasper arrived from the Bay Area startup Roofstock, which linked investors with rental properties available for purchase. It partnered with lenders including Colony American Finance, a company founded by Tom Barrack, the close Trump associate. This link to Trump, combined with Kasper’s background in one sliver of the housing realm, was enough to win her a place as one of the minders appointed by the White House to keep an eye on each government department, a powerful role without precedent in prior administrations.

Kasper, the holder of an MBA from NYU’s Stern School of Business, took her new management role seriously, asserting herself as the final arbiter in the absence of a confirmed secretary. This led to friction both with career housing policy experts and with Carson loyalists, notably Singleton, who had also been hired on. At meetings, Singleton said, Kasper was often “misrepresenting” herself as standing in for Carson. “I made it clear, ‘You don’t speak for Dr. Carson.’ She said, ‘Well, the White House …'” To which Singleton said he responded, “I get what the White House has selected, and I respect that, but he’s the secretary and you need to make sure you understand that.”

That friction lasted only so long. In mid-February, an administration “background check” on beachhead team hires turned up an op-ed critical of Trump that Singleton had written for The Hill before the election. Security personnel came to notify him that it was time to go.

On March 6, Carson arrived for his first day of work at headquarters. In introductory remarks to assembled employees, after he’d gotten the mic back from his wife, he surprised many by asking them to raise their hands and “take the niceness pledge.”

He also went on a riff about immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, capped by this: “That’s what America is about, a land of dreams and opportunity. There were other immigrants who came here in the bottom of slave ships, worked even longer, even harder, for less. But they, too, had a dream that one day their sons, daughters, grandsons, granddaughters, great-grandsons, great-granddaughters, might pursue prosperity and happiness in this land.”

The assembled employees stifled their reaction to this jarringly upbeat characterization of chattel slavery. But in HUD’s Baltimore satellite, where many in the heavily African-American office were watching the speech on an online feed at their desks, the gasps were audible.

Carson’s arrival brought with it a reckoning for career employees: Yes, this person was really in charge. They responded in strikingly different ways. The most progressive-minded were thrown into a sense of crisis: whether to hightail it to avoid whatever radical shifts or indignities were in the offing, or to stay put for the sake of the department’s programs and the millions of people they served.

Then there were the opportunists, those who saw in the vacuum in the upper ranks, where it was taking unusually long to appoint political deputies, the chance to claim higher stations than career employees would typically be able to attain. “There were a couple people in some meetings who were bending over to ingratiate themselves” with the transition team, said Harriet Tregoning, a top Obama appointee in HUD’s Community Planning and Development division, who left in January. “For some, it might be their political leaning. For some, it might be an attempt to gain influence. I saw it happening even while the Obama people were still in the building.”

Finally, there were the clock-punching lifers, the “Weebies” (“We be here before you got here, and we be here after you’re gone”), who recognized a chance to start mailing it in. “It’s ‘I can now meet people for a drink at five,'” said Tregoning. Or, as a supervisor in one branch office put it: “As a bureaucrat, HUD’s an easier place to work if Republicans are in charge. They don’t think it’s an important department, they don’t have ideas, they don’t put in changes.” Left unsaid: that such complacency was an unwitting affirmation of the conservative critique of time-serving bureaucrats.

To the extent that the new leadership was providing any guidance at all, it was often actively discouraging initiative on the part of employees. Shortly after the inauguration, a directive came down requiring employees to get 10th-floor approval for any contacts outside the building—professional conferences, or even just meetings with other departments. Ann Marie Oliva, a highly regarded HUD veteran who’d been hired during the George W. Bush administration and was in charge of homeless and HIV programs, was barred from attending a big annual conference on housing and homelessness in Ohio because, she inferred, some of the other speakers there leaned left.

The department leadership was also actively slowing down new initiatives simply by taking a very long time to give the necessary supervisory approvals for the development of surveys or program guidance. In some cases, this appeared to be the result of mere negligence and delay. In other cases, it appeared more willful. For one thing, there was the leadership’s strong hang-up about all matters transgender-related. The 10th floor ordered the removal of online training materials meant, in part, to help homeless shelters make sure they were providing equal access to transgender people. It also pulled back a survey regarding projects in Cincinnati and Houston to reduce LGBT homelessness. And it forced its Policy Development and Research division to dissociate itself from a major study it had funded on housing discrimination against gay, lesbian and transgender people—the study ended up being released in late June under the aegis of the Urban Institute instead.

More upsetting for many ambitious civil servants than the scattered nays coming from the 10th floor, though, was the lack of direction, period. Virtually all the top political jobs below Carson remained vacant. Carson himself was barely to be seen—he never made the walk-through of the building customary of past new secretaries. “It was just nothing,” said one career employee. “I’ve never been so bored in my life. No agenda, nothing to move forward or push back against. Just nothing.”

On May 2, I went to the Watergate to see Carson address an assemblage of the American Land Title Association, title attorneys in town for a regular lobbying visit to buttress the crucial support that HUD and others in Washington provide to the American home-buying machine. I was hoping the speech would give me a better sense of what Carson had in mind for the department, which had been hard to elucidate in his few public appearances. Up to that point, he’d made only a few headlines—for getting caught in a broken elevator at a housing project in Miami; for declaring, on a later visit to Ohio, that public housing should not be too luxurious, a concern that the elevator snafu had apparently not allayed. This comment had drawn mockery but genuinely reflected his long-standing outlook on the safety net: grudging acceptance of its necessity only for those at their most desperate moments, a phase of dependency that must be as brief as absolutely possible. This philosophy was frequently intertwined with allusions to the Creator—so frequently that supervisors at one HUD division sent down word to employees that, yes, their new boss was going to talk a lot about God and they’d probably better just get used to it.

But Carson’s address to the lawyers offered little further clarity on his agenda. He opened with a neurosurgery joke. He touched on his vague proposal for “vision centers” where inner-city kids could come to learn about careers. He repeated one of his favorite mantras, that the government needs to make sure people don’t get unduly reliant on federal assistance, because “everybody is either going to be part of the engine or part of the load.” And then, in the heart of the speech, where a Cabinet secretary would normally get down to programmatic brass tacks, came this meandering riff:

“You know, governments that look out for property rights also tend to look out for other rights. You know, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of all the things that make America America. So it is absolutely foundational to our success … On Sunday, I was talking to a large group of children about what’s happening with rights in our country. These are kids who had all won a Carson Scholar [an award of $1,000 that Carson has sponsored since 1994], which you have to have at least a 3.75 grade-point average on a 4.0 scale and show that you care about other people, and I said you’re going to be the leaders of our nation and will help to determine which pathway we go down, a pathway where we actually care about those around us and we use our intellect to improve the quality of life for everyone, or the pathway where we say, “I don’t want to hear you if you don’t believe what I believe, I want to shut you down, you don’t have any rights.” This is a serious business right now where we are, that juncture in our country that will determine what happens to all of us as time goes on. But the whole housing concern is something that concerns us all.”

A few weeks later, it became clear that the “housing concern” perhaps did not concern everyone when the White House released its budget proposal for HUD. After word emerged in early March that the White House was considering cutting as much as $6 billion from the department, Carson had sent a rare email to HUD employees assuring them that this was just a preliminary figure. But as it turned out, Carson, as a relative political outsider lacking strong connections to the administration, was out of the loop: The final proposal crafted by Trump budget director Mick Mulvaney called for cutting closer to $7 billion, 15 percent of its total budget. Participants in the Section 8 voucher program would need to pay at least 17 percent more of their income toward rent, and there’d likely be a couple hundred thousand fewer vouchers nationwide (and 13,000 fewer in New York City). Capital funding for public housing would be slashed by a whopping 68 percent—this, after years of cuts that, in New York alone, had left public-housing projects with rampant mold, broken elevators and faulty boilers.

“By the time I left, almost 90 percent of our budget was to help people stay in their homes,” Shaun Donovan told me. “So when you have a 15 percent cut to that budget, by definition you’re going to be throwing people out of their homes. You’re literally taking vouchers away from families, you’re literally shutting down public housing, because it can’t be maintained anymore.”

The Trump cuts would mean that several programs would be eliminated entirely, including the home program, which offers seed money for affordable housing initiatives, and the $3 billion Community Development Block Grant program that Carla Hills, Ford’s HUD secretary, had praised to Carson at the dinner. In New York, CDBG helped pay for, among many things, housing-code enforcement, the 311 system and homeless shelters for veterans. But the grants were also relied on in struggling small towns, where they paid for sidewalks, sewer upgrades and community centers. In Glouster, Ohio, a tiny coal town that went for Trump by a single vote after going for Obama two to one in 2012, officials were counting on the grants to replace a bridge so weak that the school bus couldn’t cross it, forcing kids from one part of town to cluster along a busy road for pickup.

“Without those funds, it would just cripple this area,” said Nathan Simons, who administers the grants for the surrounding region. HUD, for all its shrinking stature and insecurity complex, has over time worked its way into the fabric of ailing communities throughout the country, a role that has grown only larger as so much of Middle America has suffered decline, and as the capacity of so many state and local governments has withered amid dwindling tax bases and civic disengagement. On my travels through the Midwest I’ve seen how many federally subsidized housing complexes there are on the edges of small towns and cities, places very far from the Bronx or the South Side of Chicago. People living in these places rely on a functioning, minimally competent HUD no less than do the Section 8 voucher recipients in Jared Kushner’s low-income complexes in Baltimore. In an age of ever-widening income inequality, the Great Society department actually plays an even more vital role than when it was conceived.

But if Carson was troubled by the disembowelment of his department, he showed no sign of it. Even before the final numbers were out, he had assured housing advocates that cuts would be made up for by money dedicated to housing in the big infrastructure bill Trump was promising — a notion that his fellow Republican Kemp, among others, found far-fetched. “I’m not sure he understood how that would work,” Kemp told me. “He was probably repeating what had been told to him.” Then, a day after the budget was released, Carson downplayed the importance of programs for the poor in a radio interview with Armstrong Williams, saying that poverty was largely a “state of mind.” This, more than anything, seemed to be a crystallization of the Carson philosophy of HUD: that privation would be solved by the power of positive thinking, that his own extraordinary rise was scalable and could be replicated millions of times over.

Two weeks later, Carson went to Capitol Hill to testify on the budget proposal before congressional panels that would have the final say on the numbers. With Kasper perched over his shoulder, he told both the Senate and House committees that they shouldn’t get overly hung up on the cuts. “We must look for human solutions, not just policies and programs,” he said. “Our programs must reach out and so must our hearts.” The budget, he added, would “help more eligible Americans achieve freedom from regulations and bureaucracy and the ability to govern themselves.”

Members of both parties on the panels seemed dubious. Even conservative Republicans challenged the elimination of CDBG and dismissed Carson’s repeated claim that those and other cuts would be made up for with “public-private partnerships,” noting that such partnerships depended on exactly the public seed money that the budget was jettisoning.

Carson remained unruffled. The cuts were made necessary by the “atmosphere of constraint” created by a “new paradigm that’s been forced on us,” he said, presumably referring to the desire for tax cuts for the wealthy and an even larger military. “The problem that faces us now as a nation will only be exacerbated if we don’t deal with them in what appears to be a harsh manner,” he told the Senate panel. “We have to stop the bleeding to get the healing.”

As I watched the hearings, it occurred to me that Carson was the perfect HUD secretary for Donald Trump, the real-estate-developer president who appears to care little for public housing. He offered a gently smiling refutation to accusations from any corner that the department’s evisceration would have grave consequences. After all, Ben Carson had made it from Detroit to Johns Hopkins without housing assistance, a point of pride in his family. Not to mention that Carson’s very identity—theoretically—helped inoculate the administration against charges of prejudice. (Just last week, Carson said, in the wake of racially tinged violence in Charlottesville, that the controversy over Trump’s support of white supremacists there was “blown out of proportion” and echoed the president’s “both sides” language when referring to “hatred and bigotry.”)

Even better, Carson could be trusted not to resist Mick Mulvaney’s budget designs. At one moment in the Senate hearing, Carson noted that Congress’s recent spending package for the current year had given the department more than it had been expecting. “I’m always happy to take money,” he said, smiling. Sen. Jack Reed of Rhode Island, the committee’s top Democrat, was unamused. “You have to ask for it first,” he said.

Over at headquarters, the department remained rudderless. By June, there was still no one nominated to run the major parts of HUD, including the Federal Housing Administration and core divisions such as Housing, Policy Development and Research, Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity, and Public and Indian Housing, not to mention a swath of jobs just below that level. (Across the administration, Trump had by the end of June sent barely more than 100 names to the Senate for confirmation, fewer than half as many as Obama had by that point in 2009.) Even the stern hand of Kasper was gone—she had been moved to a perch at Ginnie Mae, the arm of HUD that provides liquidity to federal home ownership programs.

The rank and file (whose department book club reading for the summer was “The Employee’s Survival Guide to Change”) took comfort that the two senior nominations that had been announced, for deputy secretary and the head of the Community Planning and Development division, were conventionally qualified. But appointments further down the ranks were alarming.

There was the administrator for the Southwest region: the mayor of Irving, Texas, Beth Van Duyne, who had gained notoriety by warning against the gathering threat of Sharia. She had asked the Texas Homeland Security Forum to help investigate the legality of an Islamic tribunal in North Texas and had taken to Glenn Beck’s talk show to defend the arrest of the Muslim boy who’d brought a homemade clock to school. There was the conservative commentator John Gibbs, who was hired as a “special assistant” in Community Planning and Development. Sample headlines from his columns in The Federalist: “Voter Fraud Is Real. Here’s the Proof”; “If He Really Wants to Help Blacks, Colin Kaepernick Needs to Put Up or Shut Up.”

Then there was Christopher Bourne, the retired Marine Corps colonel who’d served as the policy director of Carson’s presidential campaign. He suddenly showed up as a “senior policy adviser” in Policy Development and Research. “We don’t know what his job is, and as far as I know, he doesn’t know what his job is,” said one of his new colleagues.

In the context of such hires, it did not stun many HUD employees as much as it did the broader public when news broke of the selection of Lynne Patton, the Trumps’ event planner (whom tabloids gleefully referred to as a wedding planner, for her unofficial advisory role on Eric Trump’s nuptials), as regional administrator for New York and New Jersey. It had been plain to see that Patton had been striving to prove that she was no mere hanger-on. She had been visiting senior career staff for a crash course on housing policy. She had helped organize Carson’s listening tour trips, for which her event planning background had prepared her well. And she eagerly tweeted out defenses of him—”Let’s be clear: You can make life too comfortable for anyone—rich or poor—when you do, it’s a disservice,” she declared after his comments on cushy public housing.

Yes, she would now be the chief liaison from HUD headquarters to a region with the largest concentration of subsidized housing in the country—including the huge Starrett City complex in Brooklyn co-owned by Trump—a job once held by Bill de Blasio. (“Normally, these positions go to people who know what they’re doing,” said one longtime staffer at headquarters.) And yes, she would, just a few weeks later, respond to liberal criticism of the department’s decision to approve Westchester County’s long-litigated desegregation plan with a tweet that ended with the words “P.S. I’m black.”

But there were many other things for career employees to worry about that weren’t getting as much attention. Such as what Carson had in mind with the vague “incentivized family formation” push (which falls under the community building part of HUD’s antipoverty mission) that his team had included in a briefing for Hill staffers.

Also worrisome was what the new leadership might do with major Obama-era initiatives, like its desegregation initiative, which, in a 2015 rule called Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, required local jurisdictions to come up with ways to reduce segregation or risk losing HUD funding. Carson had written an op-ed against this during the campaign, calling it a “mandated social engineering scheme” and comparing it to a “failed socialist experiment,” and Republicans in Congress were dying to kill it, but so far, the department was still going through the motions with it.

Then there was the mystery of why Carson’s family was taking such a visible role in the department. There was the omnipresent Mrs. Carson. Even more striking, however, had been the active role of the secretary’s second-oldest son. Ben Carson Jr., who goes by B.J. and co-founded an investment firm in Columbia, Maryland, that specializes in infrastructure, health care and workforce development, was showing up on email chains within the department and appearing often at headquarters. One day, he was seen leaving the 10th-floor office of David Eagles, the new COO, who was crafting a HUD reorganization to accompany the cuts.

And finally, there was the beginning of what appeared likely to be a stream of committed career employees quitting. Ann Marie Oliva, the anti-homelessness director, had met with mistrust from the 10th floor, and she was startled when she wasn’t asked to offer input for a speech Carson was giving on homeless veterans. She gave notice in late May, prompting calls from both parties on the Hill saying how sorry they were to see her go. “It is sad,” she told me, “because it’s not partisan and it could’ve been different from the beginning.”

In early July, Ben Carson went on the next leg of his listening tour: Baltimore. I was expecting the department to make a big deal of his return to his longtime home city. But instead, after the poor press coverage from the previous rounds of community outreach, the itinerary for the first day was kept private.

I managed to get my hands on the schedule and tagged along with a photographer. This did not please Carson’s entourage, which included, among others, a high-strung advance man in a bow tie, several security officers, Candy Carson, Ben Jr. and even his wife. When we arrived at the café where Carson and his family were having lunch with the mayor of Baltimore, Bow Tie arranged to have the Carsons rush out through the kitchen area to a back alley to avoid us. When, at the next stop, I was accidentally allowed into a meeting that Carson was holding at the city’s housing authority, Bow Tie leaped across the room to eject me. By the next stop, at a tour of the redevelopment near Johns Hopkins Hospital, one of the federal agents guarding Carson took my picture as I stood on the sidewalk chatting with a neighbor. By the last stop, dinner with Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan at a deluxe waterfront restaurant opened by Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank, I was unsurprised when a Carson aide went to the maître d’ to report my presence at the bar. This was Trumpian anti-press spirit taken to a new level: protectiveness of a government executive to the point of seeking invisibility.

The day had had its awkward moments. In his visit to the Baltimore HUD office, Carson caused friction with his suggestion that staff needed to work harder, comparing the federal work ethic unfavorably with the long hours he put in as a surgeon. Employees were also struck by how he kept seeming to look to his wife for cues as he spoke. At a later meeting with public health officials and researchers, which his wife, son and daughter-in-law also attended, he kicked things off 15 minutes early and referred to those who arrived on time as being late. He demurred when asked by the city’s former Health Commissioner Joshua Sharfstein if he’d commit the department to an ambitious reduction in child lead poisoning, saying something to the effect that he needed to be careful about setting big goals because he “worked for a guy who, if you don’t meet your goals, he’ll so skewer you.”

The next morning, Carson held photo ops at two homes that had undergone HUD-funded lead abatement. At the first home, he looked confused when workers explained that one of their first steps had been to make sure the home’s doors closed properly in the door jambs. “What does that have to do with lead?” asked the nation’s secretary of housing. The workers explained that a key to reducing lead paint flaking was to reduce the friction involved in opening and closing windows and doors. A moment later, a deputy housing commissioner noted that the work had been made possible in part by Community Development Block Grants, which Trump’s HUD budget eliminated.

Ben Carson Jr. resurfaced at the second day’s other open event, a visit to a health fair in East Baltimore. I watched with some amazement as the younger Carson, clad in tinted aviator shades, circulated among those seeking his father’s attention. At one point, Carson Jr. was approached by two entrepreneurs he knew who were hoping to pitch HUD on a proposal to use public housing as the site to pilot their for-profit venture replacing cash bail with the relinquishing of guns. Carson Jr. heard them out and then said, “Have you talked to Dad?” He then led them over to a clutch of Carson’s HUD aides to make introductions.

A moment later, I asked Carson Jr. why he was taking such an active role on the Baltimore trip. “With anything where we can be helpful, if Dad asks us to come along and help out, we’ll always do that. We’re here to offer support, whatever we can do,” he said. I asked about all the time he was spending at HUD headquarters. “If you’re a concerned citizen and you’re not spending time in D.C. trying to actually make sure the right things are happening, then you probably could do more,” he said. “You should have access to your public officials, and if that’s not allowed, then there’s a big problem with how the representatives are handling their relationship with citizens.” (Never mind that in this case, the “public official” was his own father.)

Later, I asked Ben Carson for a comment on his son’s role. “Ben Carson Jr. has visited me, but he has no role at the department,” he said through a spokesman. It was hard to know what to make of it all. On the one hand, it bore obvious similarities to the proliferation of Trumps and Kushners inside the White House, with all their attendant business conflicts.

But it was also possible that Ben Jr., and his mom, were so often at his father’s side for just the reason Ben Jr. claimed, to provide support. Because it was not hard to see why Carson would feel insecurity. He had been chosen for a job he had few qualifications for by a man who had few obvious qualifications for his own job, and he was now being left to his own devices to defend the dismantling of the department he was supposed to run, with an underpopulated corps of deputies at his side. (Even by mid-August, the Office of Public and Indian Housing, which spends tens of billions per year, did not have any senior political leadership whatsoever.) It was as if the White House were ensuring that whatever mere starvation failed to accomplish at HUD, indifference and mismanagement would finish.

The day before, as I waited outside the school building where Carson was meeting with the public health experts, a young mother, Danielle Jackson, had come along with her three young daughters. She asked me what was going on inside, and I told her. She said she herself had been on the waiting list for a Section 8 voucher for three years, and she seemed to take the fact that the famous Baltimore doctor was now running HUD as an omen. “I hope something good happens,” she said brightly.

Her optimism was shared by Carson himself. When I asked him at a brief press conference behind one of the lead-abated homes the next morning how things were going so far for him at HUD, running a big federal department with no prior experience in government, he shrugged. “It’s actually a challenge to inject common sense and logic into bureaucracy, there’s no question about that,” he said. “But it’s coming along quite nicely.”

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for their newsletter.