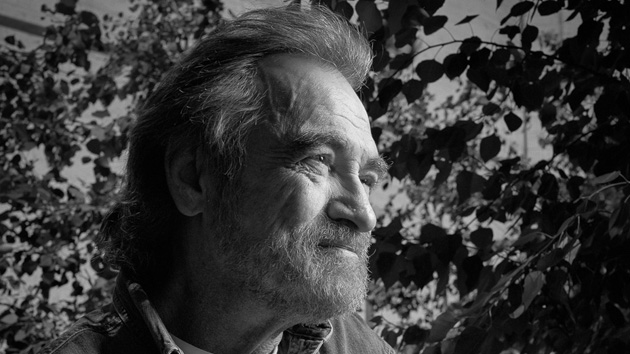

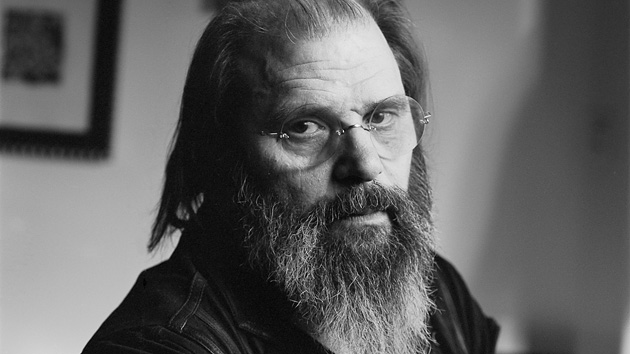

The debut of Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams as a musical duo was decades in the making. Husband and wife, they have long pursued largely independent creative careers that have taken them around the globe many times. Campbell, a virtuosic and versatile multi-instrumentalist, has been a go-to session musician and producer since the 1980s. He later spent eight years backing Bob Dylan on tour and was an integral part of recording 2001’s Love and Theft. Williams, who moved from rural Tennessee to New York City to pursue acting and musical theater, found a niche playing roles that complimented her Southern background and powerful, country-inflected voice. Campbell happened to be the pedal-steel player in a band Williams put together at New York City’s Bottom Line more than 30 years ago—and the rest was history.

After leaving Dylan’s band in 2004, Campbell answered the call from Levon Helm, drummer and singer with The Band, to serve as musical director at the “Midnight Ramble,” the intimate concert series at Helm’s home studio in Woodstock, New York. At Helm’s invitation, Williams came on as a regular singer. Campbell also co-produced two Grammy winning albums with Helm—2007’s Dirt Farmer and 2009’s follow-up Electric Dirt.

Sharing the stage regularly allowed Campbell and Williams to warm up to the idea of recording together. Their eponymous debut—a satisfying, tightly constructed roots-rock album—showcases the chemistry of a supportive marriage and reflects Campbell’s deep talents as a player and producer. I caught up with the pair in Brooklyn, on tour with Jackson Browne.

Mother Jones: Teresa, I gather your family was in agriculture.

Teresa Williams: Cotton was king. My family were essentially subsistence farmers. They were kind of the last vestige of that pioneer thing, where you fix things yourself and going into town is a major event. We’ve been on the same land, basically, since they took it from First Nation, early 1800s. And the community was insular.

MJ: But the family was very musical?

TW: Yeah, that’s what you did. After supper, you either read or you played music. My mother would be playing piano on the opposite wall of my bedroom, studying with a mail-order home piano course, which she taught me from after she had learned the songs. Daddy was playing guitar by ear. We would sit and sing and do harmonizing: Hank Williams, Everly Brothers, Johnny Cash, Jimmy Rodgers, and that kind of stuff. We heard Top 40 radio out of Memphis, so I got some rock and roll. We had a stereo, but I don’t even know if we had five records, it was just not something you spent money on. When we got older my brother had a diverse album collection.

I had a principal who grabbed me and three other little girls in first grade and put us in a little group and would trot us out to the March of Dimes talent contest and the county fair and whatnot. In the eighth grade, we branched out and did “Harper Valley PTA.” My parents refused to let me sing it in the county fair because they felt like it was little too racy for an eighth grader.

MJ: Larry, tell me about your New York City upbringing.

Larry Campbell: My parents were sort on that Bohemian fringe. They were working-class people, had jobs, but they were free thinkers. They had an incredible record collection, including the Harry Smith anthology. So as a kid I’m into Jimmy Rodgers and Harry Smith and the Weavers and Woody Guthrie and Broadway shows and grand opera and Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra—all this stuff being played all day. I didn’t realize the impact it was having on me.

February 9, 1964: The Beatles are on Ed Sullivan, and I am firmly in the middle of that generation that was just transfixed. Literally the next day, music becomes a whole different thing to me. Here’s these guys that have something that belongs to us—it’s not your parents’ music, it’s not Elvis, it’s something brand new. I started branching out into, “Where’d they get this from?” Then I’m starting to appreciate all the music that I was exposed to up until that point. I started playing guitar in ’66 and spent the rest of that decade at the Fillmore East, almost every weekend—whoever was playing. Everything was exploration, turning over stones. The Beatles’ second record has a Chuck Berry song on it; I find out who Chuck Berry is and go from him to B. B. King, Albert King, and back to Robert Johnson and Blind Blake. Then I’m seeing Hendrix at the Fillmore and the Grateful Dead in Central Park, and Jefferson Airplane, and Big Brother and the Holding Company—every important and not-so-important act of that era.

MJ: You’re self-taught?

LC: I am. I would hear something that would knock me out, and then cannibalize it. To learn a guitar solo note for note, I’d sit down with the record for as long as it took. That country music bug got me real early. I decided I gotta learn how to play the fiddle, the pedal steel, the mandolin. I followed the same route: Sit down with these records until you wear them out. I also watched people and asked questions and tried to get exposed to as much live performance as I could.

MJ: Teresa, tell me about your transition from Tennessee to New York City.

TW: I studied straight acting in school, and then I went into an MFA program and finished with a directing degree. My first job in New York was as a opening act and background singer for Eddy Arnold, the “Tennessee Plowboy.” He grew up 30 minutes from where I did, so it’s ironic that I would come to New York and get that job. That’s how I was being cast, as “rural mountain woman.” I loved it! I played the Sara Carter role in the Original Carter Family show. I kept getting jobs like that. I thought I’d come to New York and be doing Shakespeare!

MJ: Larry, what was it like the first time you visited Teresa’s family?

LC: It was special. Her parents were wonderful to me. Her community is about as rural as you can get. I could sense a subtle mistrust, not from them, but from the community. I understood the culture a little bit, because I had made it a mission to absorb southern culture since I first left New York and was transfixed by the music of the South. I spent a couple of years in Jackson, Mississippi, and I lived in Austin for a while. Growing up in New York, the South was Beverly Hillbillies, Andy Griffith, and He-Haw. It was all parody. But the music was so deep to me in every respect. You can’t really absorb the music unless you understand the culture. The time I was in Mississippi, I spent a lot of time being quiet and just listening and observing. So when I got down there with Teresa’s family, it was kind of familiar. I played the fiddle, and that really breaks down a lot of walls.

MJ: I know you’d traveled to the South to be around that music, what was happening at the time?

LC: Before I was in Mississippi, I went out to LA to get rich and famous. [Laughs.] It didn’t quite work out. I spent a lot of time starving, playing on street corners and playing talent shows. I eventually got with a band, a guy named Ben Marney who was on Playboy records. It was a country band, and we traveled, playing mostly hotel lounges. Ben had a strong following in Jackson, and we ended up playing in a club there for a couple years.

Jackson was a perfect place to absorb all this culture. And there was Malaco Studios, where I started putting my foot in the water of developing as a studio musician. I would play on gospel records, and some of the soul records and country records. Around ’78, I realized I was really comfortable and needed some more anxiety in my life, you know? It was time to go back to New York. I just happened to hit it in the middle of all this Urban Cowboy nonsense. That movie had just come out—the Travolta film after Saturday Night Fever. It was over-the-top, but country music became fashion. All of a sudden all these clubs are opening up that have mechanical bulls in them.

TW: Stone-cold New Yorkers walking down the street in cowboy hats and boots.

LC: The upside was there were a lot of great country musicians moving to New York and a lot of places to play real country music. The jingle scene started up in the advertising world, and they’d need a pedal steel player, a fiddle player, a mandolin player—all this work started coming my way. Also, the Lone Star Cafe opened up in 1976, which became sort of the mecca of what’s become known as Americana. All the blues guys played there, all the country guys, the gospel quartets, cats from New Orleans. I sort of became a house musician. I was also playing in a band with Buddy Miller, and I ended up working with Doug Sahm and toured with him for a while. This all started gestating around ’78. I met Teresa in ’86. Up until then, the studio recording scene around New York was really happening. This city was alive with music, and it hasn’t been that way since. This was coinciding with the disco era—for a while it sort of usurped it. But at the end of the ’80s, the live-music scene just sort of fizzled out.

MJ: Larry was touring with Dylan while you, Teresa, were busy with theater. How did you maintain the relationship?

TW: I’d have Mondays off and typically he would too. We would watch a TV show on the phone together. That was our little date.

LC: It was cool. But you know why it worked: You want to be with this person, you miss the person, that ache is there. I think ultimately the reason we were able to do it is because she was doing something she needed to do, it was part of who she was. I was doing something that I needed to do and was part of who I was.

TW: Which is how we met. When I got to New York my brother died, and I went out on a limb and started doing little demos of my own music. That’s when I met Larry. I thought that “New York country musician” was an oxymoron because they just didn’t get it. I was stunned that he did…He was the first guy I met who was utterly supportive of my work. People before him would profess to be, but then they’d come backstage and you could see they couldn’t handle it. He’s the first person I even dated who really was, “Go. Do. Be.” That’s massive.

JB: How did your involvement with Levon Helm and the Midnight Rambles lead to what you’re doing as a duo?

LC: That was really what got the ball rolling. I left Dylan’s band at the end of ’04. Levon called me up and said, “C’mon up here and make some music!” His voice was starting to come back after his cancer treatment, and Amy, his daughter, got it in her head that we should come up and start recording with him, just sitting around playing some old tunes. Amy had heard Teresa and I sing together at this little bar in the Village and suggested that Teresa come up too. That was the genesis of the Dirt Farmer record. From that, Levon got the idea that Teresa should come up and perform at the Rambles, too.

MJ: Those shows are legendary.

LC: Levon was at a point where all he wanted to do was have a good time playing music. And that was infectious. If you’re gonna go out there and do this, you’d better have a good time, because there’s no point otherwise. Every show we did with him was uplifting. You couldn’t wait for the next one.

TW: There was an innocent, childlike quality about the whole experience. Levon wasn’t an innocent—he had already lived quite a few lives—but he had that way about him. There was this kind of joyful feeling, like a little kid getting to play.

MJ: So is working as a duo just an experiment, or do you see a lot more of it in your future?

LC: We’re not thinking about it. We’re just gonna walk down this road until it leads us off a cliff. It’s incredibly satisfying: You’re doing the thing you love to do the most with the person you love to be with the most.

TW: My only hitch is my parents. Somebody asked the other day, “If you didn’t have this life, what would be your other life?” One of the possibilities is just to have stayed on the farm. My parents have a lovely life down there digging in the earth, planting things, and being present for friends and family when they need you. I keep trying to get him to be based out of Tennessee. We could have a dog!

MJ: What are your biggest challenges working together?

TW: It helps to have two hotel rooms.

LC: Adjoining rooms. I’ll get up from bed early and go to the other.

TW: But if there are no adjoining rooms, I still want the other room. Because that’s a lot of “together.” I need a lot of alone time or I’m not a happy camper. I have to have blankness. He’s like a political junkie—TV 24/7. I just need some silence. And two bathrooms will save a marriage. Any woman will tell you, too.

You can catch Larry and Teresa at their upcoming tour dates in the United States.

This profile is part of In Close Contact, an independently produced series highlighting today’s leading creative musicians. To be part of it and help this work continue, visit www.pledgemusic.com/inclosecontact.