Photo illustration by Ivylise Simones. CIA Photo: David Goldman/AP

On Tuesday morning, the Senate intelligence committee released an executive summary of its five-year investigation into the CIA’s interrogation and detention program. (Read the executive summary here.)

Among the report’s most striking revelations is that CIA interrogators were often untrained and in some instances made up torturous techniques as they went along.

The CIA was “unprepared” to begin the enhanced interrogation program, the Senate report concluded. The agency sent untrained, inexperienced people into the field to interrogate Abu Zubaydah, the first important Al Qaeda suspect the US captured.

Within weeks of Zubaydah’s arrival, while he was still in the hospital recovering from a gunshot wound, CIA headquarters was planning to throw him in all-white room with no natural lighting, blast rock music 24/7, strip him of his clothes, and keep him awake all day. They did. Extreme interrogations like these, identified as “enhanced interrogation techniques,” went on for more than three months before CIA officers received any sort of training in the new techniques from anyone.

As the overall detention and interrogation program proceeded, many untrained CIA personnel continued to do whatever they wanted, without authorization or supervision. At one facility in 2002, code-named COBALT, “untrained CIA officers…conducted frequent, unauthorized, and unsupervised interrogations of detainees using harsh physical interrogation techniques that were not—and never became—part of the CIA’s formal ‘enhanced’ interrogation program,” the report found. COBALT is reportedly a prison in Afghanistan the agency nicknamed “the Salt Pit.” In one example identified by the report, an interrogator left a COBALT detainee chained naked to the concrete floor. The detainee later died of suspected hypothermia.

The CIA also put a junior official with absolutely no relevant experience in charge of this entire facility. Later, when the CIA’s inspector general investigated COBALT, the CIA said it knew little about what happened there. Several interrogators at the site became uncomfortable with their coworkers’ methods, not sure that they were safe or effective. According to John Helgeron, the CIA inspector general who conducted a formal review of the agency’s detention and interrogation program, CIA interrogators at COBALT had zero training guidelines before December 2002. The report claims, quoting Helgeron: “Interrogators, some with little or no training, were ‘left to their own devices in working with detainees.'”

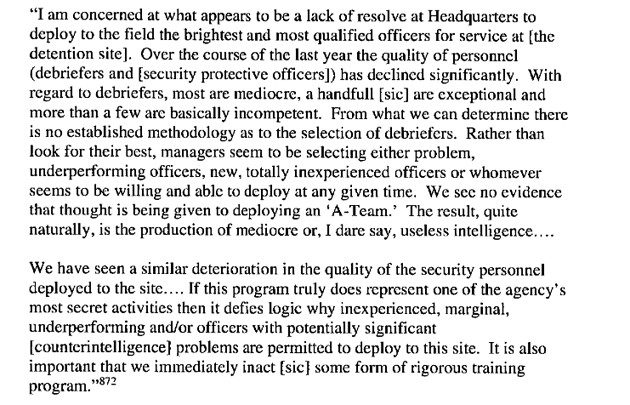

In 2004, the CIA chief at another detention site, code-named BLACK, penned a long email about his disillusionment with the program, especially deficiencies in training:

And in one particularly heinous example, the CIA headquarters sent an untrained interrogator to question Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, a man the CIA claimed was an Al Qaeda “terrorist operations planner” involved in several bombings. One senior CIA official had reservations about sending the untrained interrogator, noting that he heard the man was “too confident, had a temper, and had some security issues.” But the man got sent anyway.

While there, the interrogator allegedly forced Nashiri to stand with his hands over his head for two and a half days, blindfolded him, pushed a pistol up against his head, and revved up a cordless drill close to his body. When this produced no new information, the interrogator slapped the detainee repeatedly on the back of the head, told him he’d sexually assault his mother in front of him, blew cigar smoke in his face, and made him sit in such stressful positions that a medical officer was concerned the detainee’s shoulders would be dislocated.

The CIA base chief let this happen because he thought this interrogator was sent to “fix” the problem of an uncooperative detainee and had permission from headquarters to take such extreme steps. Both men were later reprimanded, according to the report.

The problem of untrained amateurs questioning and torturing of detainees wasn’t unique to the CIA. In 2008, Mother Jones explored the world of untrained interrogators with testimony from Ben Allbright—a soldier who recalls using harsh interrogation techniques while serving as a military guard at a small Iraqi prison called Tiger in Western Iraq:

Ben was not a “bad apple,” and he didn’t make up these treatments. He was following standard operating procedure as ordered by military-intelligence officers. The MI guys didn’t make up the techniques either; they have a long international history as effective torture methods. Though generally referred to by circumlocutions such as “harsh techniques,” “softening up,” and “enhanced interrogation,” they have been medically shown to have the same effects as other forms of torture. Forced standing, for example, causes ankles to swell to twice their size within 24 hours, making walking excruciating and potentially causing kidney failure.

The Senate intelligence committee did not address allegations of torture or abuse by the US military. In fact, when members of the US military stopped by COBALT, they decided it was too risky for them to be involved at all.

In July 2002, CIA headquarters recommended that a group of interrogators, “none of whom had been trained in the use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques,” try to “break” a detainee named Ridha al-Najjar, who was arrested in Pakistan and identified as a former bodyguard for Osama bin Laden.

When officers from the US military arrived for a debriefing, the military’s legal adviser took note of the extreme techniques being used. The interrogators left Najjar hanging handcuffed to an overhead bar for 22-hour periods. He was left in total darkness and cold temperatures, hooded and shackled. They forced him to wear a diaper and didn’t provide a bathroom. And on top of that, the US military officer claimed that the warden in charge “[had] little to no experience with interrogating or handling prisoners.”

At the end of the visit, the legal adviser concluded that the treatment of the prisoner and the concealment of the facility were too big a liability for the military to get involved. But even then, Najjar’s treatment became a “model” for future interrogations, according to the report.