Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) at the Conservative Political Action Conference in January. Pete Marovich/ZUMApress

When Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) laid out a new set of proposals to revamp the federal safety net during a speech on Thursday at the American Enterprise Institute, central to his vision was the idea of consolidating federal programs to create a “personalized, customized form of aid—one that recognizes both a person’s needs and their strengths—both the problem and the potential.”

The plan, wrapped in caring language about giving the poor individual attention, has earned plaudits from both the right and the left for avoiding partisanship and offering up a concrete idea that policy makers will have to take seriously. Liberals have given Ryan—an Ayn Rand devotee who on the campaign trail reduced American society to one of makers versus takers and whose budgets have proposed slashing millions in spending on the poor—credit for getting out of the office and spending some time with actual poor people during his year-long “listening tour,” whose genuine impact is evident in his proposal.

His ideas about tailoring the safety net to the individual sound fabulous in theory—indeed, they’re not far off from what liberals have been trying to achieve for decades. But, in practice, a central component of his anti-poverty prescription is unattainable. It could only be done right at an enormous cost to the taxpayers and with the expansion of the kind of government intrusiveness conservatives like Ryan typically despise.

Ryan envisions federal benefits streamlined and delivered in a sort of one-stop shopping center. After consolidating ten or so different programs and turning them over to the states to administer as a single “Opportunity Grant,” Ryan sees a future where beneficiaries would be guided through the process of applying for housing, food stamps, and other benefits all in one place. But he also sees them getting something else: A life coach and mentor in the form of a caseworker who would use a set of carrots and sticks to nudge them into better choices, and ultimately a better life.

At AEI, Ryan explained how this might work:

Take an example. Let’s call her Andrea. She’s 24. She has two kids ages four and two. Her husband left the family six months ago, and she does not know how to contact him. Andrea graduated from high school, but her only work experience was a two-year stint in retail. She and her kids now live with her parents in a two-bedroom mobile home. Her parents can’t support her over the long haul. She’s been trying to find work for the last five months. She doesn’t have a car. She can’t afford child care. And her dream is to become a teacher.

Under this plan, Andrea would go to a local service provider. She would sit down with a case manager and develop an “opportunity plan.” That plan would pinpoint her strengths; her opportunities for growth; her short-, medium-, and long-term goals. The two of them would sign a contract. Andrea would agree to meet specific benchmarks of success, a timeline for meeting them, consequences for missing them, and rewards for exceeding them.

Andrea’s short-term goal is to find a job. But her long-term goal is to find the right job—to become a teacher. So she might find a job in retail to pay the bills. Meanwhile, her case manager would help pay for transportation and child care so she could take classes at night. Over time, Andrea could go to school, get her certification, and find a teaching job. The point is, with someone to coordinate her aid, Andrea would not just find a job; she would start a career.

Ryan isn’t the first policy wonk to call for a softer, gentler safety net where social workers held the hands of the needy, guiding and cajoling them out of poverty. Liberals have pushed this for decades. Charlie Peters, who helped John F. Kennedy evaluate the fledgling Peace Corps program and founded the Washington Monthly magazine (where I once worked) to highlight “neoliberal” ideas about reforming government, is just one example. As editor, every couple of years, he would assign a story calling for the revival of the super-caseworker as the cure to a host of ills within the federal anti-poverty apparatus. (See here.)

Neoliberal writers such as Mickey Kaus (a Washington Monthly alumnus) and eventually President Bill Clinton also got behind welfare reform and supported state-level experiments, where customized casework—like what Ryan is proposing—played prominently in many of those experiments. Unfortunately, these experiments often didn’t work out that well. Indeed, one of the most illustrative cases came in Ryan’s home state of Wisconsin.

New York Times reporter Jason DeParle (also a Washington Monthly alumnus, incidentally), spent years chronicling the impact of welfare reform in Milwaukee, which was one of those state-level hotbeds of innovation that Ryan has championed in his proposal. DeParle wrote a book on the experiment, and his reporting illustrated what individualized services looked like in practice at the local level. He focused on a caseworker in Milwaukee, Michael, a man who’d previously been “an unemployed jack of the building trades, drinking vodka for breakfast” but who was trying to do a good job. Here’s a scene from the book where he’s working for a welfare-to-work contractor and trying to identify the strengths and skills in his own version of Ryan’s Andrea:

Facing a parade of addled clients, Michael found himself thinking more about keystrokes than the substance of what they said. His befuddlement reached its dark apogee with the arrival of a large, sobbing woman free-associating about her troubles. Michael dutifully posed the questions on his screen.

Sobbing Woman: I got into it with my sister’s boyfriend….

Michael: What are your employment goals?

Woman: … he hit me in the head with a two-by-four…

Michael: Foreign languages? Written or verbal?

Woman: … we’re out of food …

Michael: Volunteer work or hobbies?

DeParle describes caseworkers in the Wisconsin welfare-to-work agencies as utterly overwhelmed, with caseloads double what they should have been because no one wanted to invest the money to hire the number of qualified people it would take to do the job right. Caseworkers like Michael were also inundated with clients who didn’t necessarily want the government or private-sector caseworkers all up in their business. Few of Michael’s generationally poor clients ended up getting real jobs, but a lot of them ended up losing their benefits. That’s one reason why, nationally, in the decade after welfare reform, the number of children in deep poverty—that is, living at below half the federal poverty line—jumped from 1.5 million to 2.2 million between 1995 and 2005.

Customizing federal safety net services, while a laudable ideal, has several major downsides. One big one: It’s slow, and someone who desperately needs food stamps to free up money to pay the rent isn’t especially well-positioned to spend a lot of time contemplating self-improvement. Jason Perkins-Cohen spent seven years working in the DC Income Maintenance Administration, helping set up the city’s welfare-to-work program. Now the executive director of the Job Opportunities Task Force in Baltimore, he says focusing on individualization ignores the fact that everyone has the same basic needs.

“So yes, everyone is an individual, but everyone needs to have shelter, food, health assistance, and a job.” Right now, he says, people can get expedited food stamps in 15 days, an important feature for desperate people in crisis. “To customize [services], you’re going to have to find out a lot more information, and all of this customization will end up slowing down the receipt of benefits.”

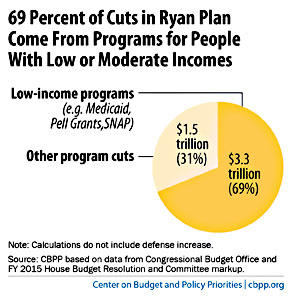

Ryan’s proposal also glosses over how much helping people like his fictional Andrea would cost. “When he presented Andrea and what she would get, it sounds nice, but where do you get the money?” asks LaDonna Pavetti, vice president for family income support policy at the nonprofit Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Individualized anti-poverty services are way more expensive than just giving people cash or food stamps, and creating such services would inevitably expand the administrative demands on any social program or limit the number of people who could be served.

Consider, as a hypothetical, the food stamp program, which Ryan thinks should require people to work as a condition of receiving the benefit (ignoring, for the moment, that nearly 60 percent of working-age adults getting food stamps already work). More than 40 million Americans get food stamps. Providing all them with a hand-holding caseworker with whom, under Ryan’s plan, they’d draft long-term plans and contracts outlining their responsibilities and goals before they’d be allowed to eat, would require a fleet of roughly more than 700,000 social workers, assuming a reasonable caseload of about 55 clients per caseworker. Social workers don’t make much money, with a median salary of about $44,000 a year. Even so, 700,000 of them would cost more than $30 billion a year, not including benefits. That’s nearly 40 percent of what the country currently spends on food stamps and nearly twice the entire federal welfare budget. By comparison, the current food stamp program delivers 92 percent of its funding directly to people in need; only 5 percent goes to administrative costs.

Here are some numbers that aren’t hypothetical: As part of its welfare reform overhaul, the state of Nebraska for several years attempted to do what Ryan seems to be proposing. Masters degree-level social workers, with tiny caseloads, delivered intensive personalized services, including home visits, to a group of welfare recipients, including a batch of extremely hard to employ single mothers. They attempted to get the women into the workforce and self-sufficient for the long haul.

The program produced better results than any such program ever had. Almost half of the study participants went to work for at least a year, double the rate of the group without the individualized attention, and their earnings increased significantly. The clients who got the individual casework were less depressed, less likely to lose custody of a child, and more likely to receive child support. But they still faced food and housing hardship; they were still poor, if working poor. And again, only half the study participants went to work.

Providing all those individualized services cost the state $8,300 per client—so much that researchers who evaluated the program concluded that the “benefits to society did not outweigh its costs during the study.” The researchers speculated that if the successful program participants stayed employed for another two years, the effort might pay off, but individually helping these folks cost about $5,000 more than what those clients earned by entering the workforce.

The families might have been ended up in a slightly better place, at least for a while, but the state of Nebraska would have been better off writing them a $5,000 check and calling it a day.

Which is precisely why the safety net today really doesn’t deliver the kind of customized service that Ryan thinks it should. It’s just too expensive, too hard to provide on a large scale, and in the end, not all that more effective than simply giving people money they need to keep the lights on until they can get back on their feet on their own. Is Ryan, whose budgets have proposed deep cuts to the food stamp and other poverty programs, really going to advocate spending billions to help all the nation’s low-income people identify their “opportunities for growth” and craft long-term goals as a condition of getting federal aid? It seems unlikely.