James Berglie/ZUMAPress

The economy added 195,000 jobs in June, according to jobs numbers released Friday by the Labor Department, and the unemployment rate held at 7.6 percent. The news was better than expected, and continues several months of generally positive employment news. But economists say that the joblessness situation in the country is not nearly sunny enough to justify the Federal Reserve reigning in the stimulus measures it has deployed since the recession, a move the Fed has hinted it may make in the coming months.

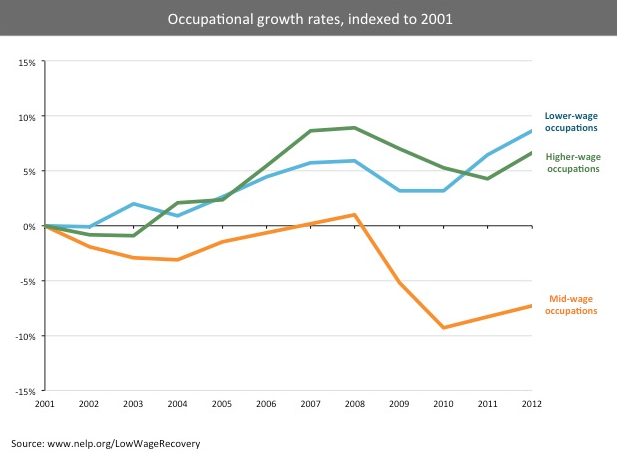

Employment growth in June was in line with the average monthly gain in jobs over the past year, and numbers for the past few months have been revised upwards—in April from 149,000 to 199,000, and in May from 175,000 to 195,000. More than 62 percent of the job increases last month were in leisure and hospitality, which picked up 75,000 jobs; retail, which gained 37,000; and temp services, which added 10,000. Low-wage service sector jobs have been a hallmark of this recovery; occupations paying less than $13.83 have accounted for 58 percent of the job gains since 2010. This follows a longer-term pattern of middle-income jobs being hollowed out by low- and high-wage jobs after recessions. Here’s what that has looked like since the 2001 recession, via the National Employment Law Project:

And here’s more grim news in June’s report: The number of people working part-time because their hours had been cut back or were unable to find full-time work increased by 322,000 people to 8.2 million between May and June. Last month, there were 1 million discouraged workers—meaning people not looking for work because they believe there are no jobs available for them. That’s an increase of 206,000 from a year ago. When you include these workers, you get an alternative June unemployment rate (which the Labor Department terms the U6 unemployment rate) of 14.3 percent. That’s a significant uptick from May (13.8 percent), and the highest level since February.

In other bad news, the unemployment rate for adult women edged up to 6.8 percent, and the ongoing sequester accounted for a loss of 7,000 government jobs.

A total of 11.8 million Americans remain unemployed, and the proportion of people in the workforce remains at its lowest level since 1979.

For these reasons, economists are saying this is no time for the Federal Reserve to cut back on stimulus measures. In May, Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke hinted the Fed may begin increasing interest rates from their current near-zero levels, and cut back on its purchasing of tens of billions of dollars per month in government bonds. Dean Baker, director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, says that the proportion of people in the workforce should drive the Fed’s stimulus policies, not the unemployment rate. Here’s Baker:

Ironically Bernanke made this exact point about declining [employment-to-population ratio (EPOPs)] back in January 2004 when he was justifying the Fed’s decision to keep the [interest] rate at what was then considered an extraordinarily low 1.0 percent. Bernanke noted that the unemployment rate at the time was not terribly high, but pointed to a sharp decline in the EPOP from the pre-recession level. Since it was implausible that so many people had suddenly lost the desire or ability to work, Bernanke argued that the falling EPOP was strong evidence of continuing slack in the labor market.

Apparently Bernanke views the recent fall in the EPOP differently than the drop following the last recession.