<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com">Chimpinski </a>/Shutterstock

Mitt Romney released more tax information on Friday. Here’s what you need to know.

He’s still only released two years’ worth of tax returns. Romney released his 2010 tax return in January. On Friday, he released his 2011 return and a very brief “summary” of the past 20 years’ worth of returns. That summary was missing the kind of detail that would have provided a full picture of Romney’s finances, rather than the incomplete snapshot the campaign has provided to date. Romney’s father, George Romney, released 12 years of returns when he ran for president in 1968.

He picked his own tax rate in 2011, purposely paying more than he owed. Romney intentionally took fewer deductions than he earned in 2011, paying over $250,000 more in taxes than he needed to.

The Romney campaign released what it says are the effective tax rates Romney paid for the past two decades. His effective tax rate was calculated based on his Adjusted Gross Income. That’s standard, but in Romney’s case, it doesn’t tell the whole story. The Romney campaign is reporting the percentage of Romney’s AGI that he paid to the government, explains Brian Galle, an associate professor at Boston College Law School who is an expert on individual and corporate income tax. AGI is the number you get after you take certain, limited deductions. The most relevant of these deductions for Romney are losses from the sale or exchange of property. That could include stock or partnership interests in Bain Capital and associated companies that were sold at a loss. The Romney campaign is disclosing the percentage of tax he paid “on the amount he got after he subtracted out all those losses,” which could have been very substantial, Galle says—perhaps even enough to almost eliminate Romney’s tax liability. That means that although Romney paid at least something in previous years, it could have been a very small amount. “He could have been paying 13.66 percent of $100 in 2009. He might have paid $13.66,” Galle continues. We won’t know unless the Romney campaign releases more information.

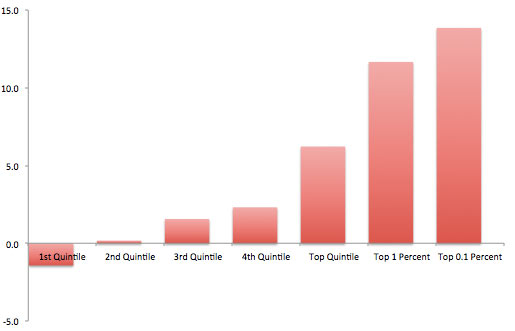

This chart shows that the gap between Romney’s adjusted gross income and the total amount he paid in taxes in 2011 far outstrips that of several former presidents.

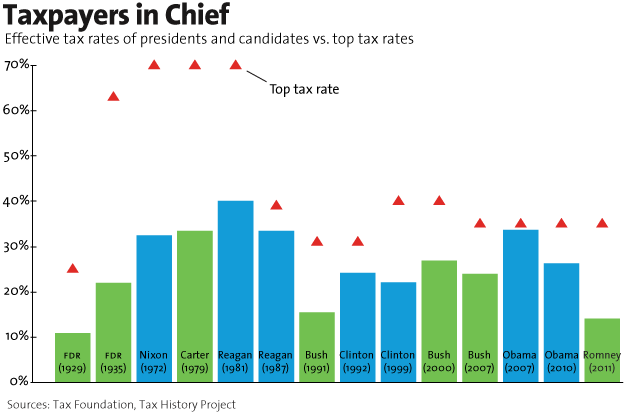

And this chart compares the effective tax rates paid by the same presidents (and Romney) compared to the top tax rate at the time.

Romney still pays taxes on his sons’ enormous trust funds. David Cay Johnston, a Reuters columnist, tax expert, and Pulitzer Prize winner, tells Mother Jones that without the taxes Romney paid on his sons’ trust funds, which are worth around $100 million combined, “his rate would be much lower.”

Romney’s advisers used an odd method to calculate how much he paid over the past two decades. As the Washington Post‘s Greg Sargent reported, Romney’s advisers averaged his tax rates over 20 years to get a number for his tax burden over that period. But it would have been more accurate to take Romney’s total tax paid over that period and divide it by his total earnings to get a new percentage. Sargent spoke to Roberton Williams, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center, about this problem:

“Let’s say you have 10 years in which you paid 13 percent in taxes, and 10 years in which you paid 27 percent,” Williams told me. “If you average those rates, you’ll get an overall rate of 20 percent. But if the 13 percent years were high income years, and the 27 percent years were low income years, then his total taxes paid as a share of total income over the 20 years would be less, perhaps significantly less, than 20 percent.”

Romney and other private equity managers get a tax break for earning investment income, but tax reform advocates think a lot of their “investment income” is really labor income. Romney has saved a lot of money over the years with the carried interest exception, a loophole that allows private equity managers—i.e., the people who run private equity funds, not the people who invest in them—to treat part of what they’re paid in fees as investment income, even though they didn’t necessarily invest the money. Often, this results in people like Romney paying a 15 percent tax rate on income that would otherwise be taxed at 35 percent. They “pretend their labor income is really investment income by calling it ‘carried interest’ and paying at a low rate,” explains Slate‘s Matt Yglesias. (It’s perfectly legal.)

Harry Reid probably owes Mitt Romney an apology. Back in July, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid told the Huffington Post that a “Bain investor” confided to him that Romney “didn’t pay any taxes for 10 years.” Reid’s allegations put Romney on the defensive for refusing to release more than two years of tax returns, but based on what we know now they’re most likely false, Galle says. “If Harry Reid had said something like he paid ‘like no taxes,’ that might be accurate,” Galle says. “It might be a quite small number potentially, but he didn’t pay nothing.”

Romney’s tax rate does not account for much of his wealth. “The income tax…doesn’t tax you on changes of the value of your stuff from year to year unless you convert that stuff into cash,” Galle explains. “If you never sell it then it doesn’t become part of your income.” A huge portion of the Romneys’ fortune—as much as $100 million—is tied up in Mitt’s individual retirement account (IRA), where it has grown tax-free for decades. That account is in the top .001 percent of all IRAs. Any increase in the value of Romney’s IRA is not counted when his income is calculated. This is true for other Americans, too, but most Americans who have IRAs—only 48 million do—have relatively small amounts of money in them. The median IRA was worth $17,863 in 2010. So, for most Americans, the IRA tax exemption isn’t the huge factor it is for Romney.

The bottom line: Most American workers don’t have significant investment income; their income is almost all wages. Factoring in his massive nonwage gains, and Romney’s “real tax rate is something like half of what he’s reporting if you were to compare him to most workers,” Galle says.