Image: Nic Dunlop/Panos

It was getting toward midnight when the phone rang in Thomas Novotny’s hotel room in Geneva. It was a May evening in 2001, and Novotny, then the assistant surgeon general, was leading the U.S. delegation to negotiations on the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, a global treaty to reduce cigarette smoking. Appointed by President Clinton, Novotny had steered the delegation along a moderate course, advocating strong public-health measures in Geneva while trying not to antagonize pro-tobacco conservatives in Congress. The American delegation championed an international ban on smoking in restaurants, trains, buses, and other public facilities. It supported mandatory worldwide cigarette taxes designed to curb smoking and save millions of lives, and it advocated a partial ban on tobacco advertising, prohibiting commercial messages that might appeal to children.

The late-night call came from William Steiger, the new director of the U.S. Office of Global Health Affairs and the godson of George Bush Sr. Although Novotny and his team had already set out their position in negotiations with 190 other nations, Steiger insisted the U.S. delegates backpedal on several key issues affecting the tobacco industry. “We had to back down on any sort of agreement for restricting cigarette advertising, any sort of pro-tax stand, and any policies on secondhand smoke restrictions,” Novotny recalls. Steiger also ordered him to oppose efforts to ban descriptive terms like “low-tar,” “light,” and “mild,” which, according to the National Cancer Institute, deceive smokers into thinking that those brands deliver less tar and nicotine than others. “The positions that we had developed, which were headed in the right direction, we had to reverse in midstream, almost in mid-sentence,” Novotny says. “It was horrible. I felt devastated.”

The phone call, Mother Jones has learned, was part of a behind-the-scenes campaign being waged by the Bush administration to water down international restrictions on tobacco. The Geneva treaty, in the works since 1999, represents an unprecedented effort to stem a worldwide epidemic that kills almost 5 million people a year. But as the treaty nears its May completion date, the Bush administration has been working quietly to ensure that the agreement does little to curb smoking, opposing strict control measures backed by most Asian, African, and European countries. In both public sessions and private conversations, “the United States has continually sought to weaken a treaty that they have no intent on signing,” says Ross Hammond, who represents the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids at the Geneva meetings.

Last October, in its most public effort to undermine the treaty, the administration announced that it would vehemently oppose any effort to phase out all cigarette advertising, saying that such a complete ban would violate freedom-of-speech protections. “It’s an absolute red line for us,” declared Kenneth Bernard, who replaced Novotny as assistant surgeon general. “There’s no way we can sign or participate in a convention that includes that. It breaks our laws and Constitution.” When other delegates proposed a middle course — allowing nations with constitutional free-speech clauses to opt out of an international advertising ban — the U.S. delegation rejected the compromise.

On other issues — taxation, secondhand smoke, misleading labels like “low-tar” — the Bush administration has brought the United States into line with positions staked out by the tobacco industry. Six weeks before the midnight phone call to Novotny, Philip Morris sent the administration a 32-page letter detailing the company’s stance on the treaty. “Simply put, we think that the Framework Convention must recognize, and reflect the reality, that smoking is — and should remain — an adult choice,” the company wrote. It then outlined 11 provisions it wanted struck from the treaty. Philip Morris opposed all additional taxes, arguing that “cigarettes are already among the highest-taxed consumer products in the world.” It also argued against regulating cigarette use in restaurants, saying such decisions “are generally best left to individual proprietors, each of whom has an economic incentive to provide a comfortable environment for nonsmokers and smokers alike.”

Philip Morris legislative counsel Mark Berlind says there were “two or three” meetings between government officials and industry leaders regarding the tobacco treaty. (The White House has refused congressional requests to release information about the closed-door conversations.) A month after sending the letter, Philip Morris contributed $57,764 to the Republican Party. One week later, Novotny was ordered to back down at the Geneva negotiations, and the U.S. delegation began advocating for 10 of the 11 deletions advocated by Philip Morris.

“It’s either an eye-popping coincidence or a testament to the insidious influence that Philip Morris has on the Bush administration,” says Rep. Henry Waxman, a Democrat from California. “The appearance is awful.”

Berlind insists the timing of the campaign contributions was coincidental, adding that President Bush has not sided with Philip Morris on every issue. “We would like to see a strong treaty that sets minimum worldwide standards that countries would have to follow but could exceed,” Berlind says. “There’s no behind-the-scenes lobbying to get countries to adopt our secret position.”

In fact, internal documents show that Philip Morris was working behind the scenes long before negotiations began. In 1997 the company hired Mongoven, Biscoe & Duchin, a Washington public-relations firm that specializes in opposing public-health efforts. In an analysis prepared that year, Mongoven warned, “The ultimate objective of the World Health Organization staff and bureaucracy is to eradicate the use of tobacco,” and suggested that Philip Morris try to thwart the treaty before it was even fashioned. “The first alternative to an onerous convention is to delay its crafting and adoption,” the report said. Mongoven also prepared a character assassination memo for Philip Morris targeting who director-general Gro Harlem Brundtland. The company insists it ignored the memo, but it was later found in a company official’s folder marked “who Planning.”

Given the Bush administration’s resistance to international treaties, health advocates doubt it will ever ratify the Framework Convention — even if it is watered down to address U.S. objections. “I think it’s basically a dead-in-the-water issue,” says Novotny, the former delegation leader and now a visiting professor of epidemiology at the University of California in San Francisco. “Getting anything signed by the president that has any teeth would be unlikely.” Some smoking opponents believe other nations should focus on passing the strongest possible treaty they can, without counting on America’s signature.

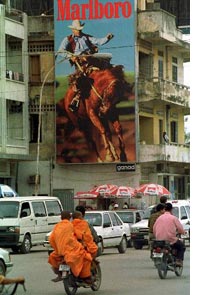

Whether or not the administration signs the tobacco treaty after it is completed in May, U.S. efforts to weaken the agreement have angered health advocates around the world. They point out that America is the world’s leading exporter of cigarettes — and that its own citizens enjoy many of the protections proposed in the treaty. “Evidently, the U.S. has misplaced its priorities,” says Phillip Karugaba, a Ugandan who represents the Environmental Action Network at the talks. “While the U.S. courts make such astounding decisions on compensation to smokers, and some U.S. cities boast of very progressive measures on tobacco control, the U.S. seems bent on depriving the rest of the world of such advantage.”