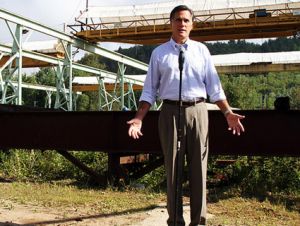

Mitt RomneyChristy Bowe/Globe Photos/ZUMApress.com

It didn’t take long—just six minutes into the 98-minute debate—for the moderators at Wednesday night’s Republican presidential debate to take aim at Mitt Romney’s record at Bain Capital, the powerful private equity firm Romney helped start. Here’s that exchange:

NBC’s Brian Williams: “Bain Capital, a company you helped to form, among other things, often buys up companies, strips ’em down, gets ’em ready, and resells them at a net job loss to American workers.”

Mitt Romney: “That might be how some people might want to characterize what we did, but in fact we started businesses at Bain Capital, and when we acquired businesses, in each case we tried to make ’em bigger, make ’em more successful and grow.

“The idea that somehow you can strip things down and [that] makes them more valuable is not a real effective investment strategy. We tried to make these businesses more successful. By the way, they didn’t all work. When it was all said and done, we added tens of thousands of jobs to the businesses we helped support.”

Some quick background: Private equity firms like Bain are known for raising money from outside investors; using that money to buy up struggling companies; restructuring the companies (think layoffs, slashing worker benefits, and selling off pieces of the business); and finally selling the (supposedly) leaner, meaner businesses for a profit. One particularly infamous type of private equity deal is the leveraged buyout, in which a private equity firm will borrow a huge amount of money to buy a company, thereby weighing down the purchased company with debt.

Now, let’s pick apart Romney’s defense of Bain. When Bain took over companies, he said, “in each case we tried to make ’em bigger, make ’em more successful and grow” [emphasis mine]. Not so in the case of Dade International, a medical testing company acquired by Bain and Goldman Sachs in 1994. As Bloomberg reported, Bain cut 1,600 jobs from the company between 1996 and 1999 after merging the company with several others as part of Bain’s restructuring plan. In 1999, Bain and Goldman sold Dade International, as it was later called, for a profit, but left the company buried in debt. It filed for bankruptcy in 2002.

Then there was the case of American Pad and Paper, an Indiana-based office products company. Bain bought the company in 1992, and seven years later, when Romney left Bain, American Pad had seen two US plants shutter, lost 385 jobs, and was hobbled by $392 million in debt.

These are, of course, just two out of dozens of deals from Romney’s 15 years at Bain. Other deals—helping to launch office goods store Staples, strengthening Sports Authority—showed how Bain could indeed improve a company. But the Dade and Ampad cases contradict Romney’s statement that Bain was always focused on jobs growth and expanding companies.

Even more of a whopper was this statement of Romney’s: “The idea that somehow you can strip things down and [that] makes them more valuable is not a real effective investment strategy.” Except that’s straight out of the private equity playbook.

This powerful New York Times story looking at how private equity companies repeatedly sold and bought the Simmons Bedding Company, in the process squeezing all the life out of the company, is a powerful antidote to Romney’s claim. (Bain was not one of those firms.) Here’s an excerpt:

Simmons says it will soon file for bankruptcy protection, as part of an agreement by its current owners to sell the company—the seventh time it has been sold in a little more than two decades—all after being owned for short periods by a parade of different investment groups, known as private equity firms, which try to buy undervalued companies, mostly with borrowed money.

For many of the company’s investors, the sale will be a disaster. Its bondholders alone stand to lose more than $575 million. The company’s downfall has also devastated employees like Noble Rogers, who worked for 22 years at Simmons, most of that time at a factory outside Atlanta. He is one of 1,000 employees—more than one-quarter of the work force—laid off last year.

But Thomas H. Lee Partners of Boston has not only escaped unscathed, it has made a profit. The investment firm, which bought Simmons in 2003, has pocketed around $77 million in profit, even as the company’s fortunes have declined. THL collected hundreds of millions of dollars from the company in the form of special dividends. It also paid itself millions more in fees, first for buying the company, then for helping run it. Last year, the firm even gave itself a small raise.

Wall Street investment banks also cashed in. They collected millions for helping to arrange the takeovers and for selling the bonds that made those deals possible. All told, the various private equity owners have made around $750 million in profits from Simmons over the years.

Simmons Bedding is hardly the only company to go through the private equity wringer. Romney may say this isn’t an “effective investment strategy,” but both Bain’s decisions and those of other private equity firms say otherwise. As for Romney’s claim that Bain added “tens of thousands of jobs” to companies it acquired, there’s no hard evidence in the public record supporting that claim. You’ll just have to take Mitt’s word on it.