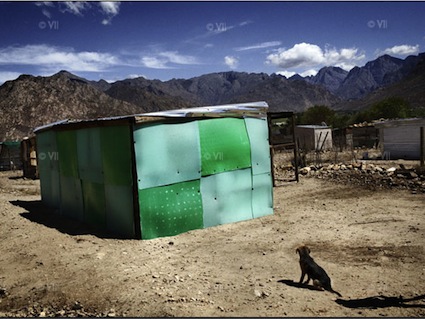

Vines in South Africa's celebrated Stellenbosch wine region. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/timparkinson/170392012/">Tim Parkinson</a>/Flickr

In an Aug. 31 post called “South Africa’s Wine Woes,” I discussed a recent report from Human Rights Watch on labor conditions in South Africa’s wine industry called Ripe with Abuse: Human Rights Conditions in South Africa’s Fruit and Wine Industries (PDF).

Directly below is a rebuttal from Adam Welz, a South African-born filmmaker, writer, Mother Jones contributor, and photographer now living in Brooklyn. My response to Welz follows.

“South Africa’s Wine Woes” is a great example of how an incomplete story written far, far away from the action can do more harm than good. The uncritical embedding in the story—and thus apparent endorsement—of a sensationalist and even more incomplete video makes it worse.

I’m a South African filmmaker, writer and researcher who until recently lived near the Cape winelands. Over about five years I spent many months poking around in the back fields of tens of wine farms, speaking to workers and farmers alike about many aspects of the industry. I’m not a wine expert or a foodie, just a curious guy with a background in biology and economics.

Reading “Wine Woes” and watching the accompanying video may well lead the average MoJo reader to believe that in the Cape wine industry it’s routine for workers to live in animal sheds with no clean water. It’s not.

During my time in the vineyards I encountered a single farm where workers were as badly treated as the poor family featured in the first part of the video. The farm owner, as it turned out, was a violent alcoholic whose wife had left him and was despised by his neighbors—hardly an exemplary member of the agricultural community.

The local government labor inspector and local union rep wasn’t interested in his workers’ plight because they were “coloured,” not “black”—in other words they were Afrikaans-speaking, mixed-race descendants of the original “Khoi” or “Hottentot” inhabitants of the Western Cape. “Coloured” people are less likely to support the ruling African National Congress (ANC) or join their affiliated unions than “black” Xhosa people who have in recent decades migrated to the winelands from the Eastern Cape. The ANC-aligned labor inspector and union were interested in building a power base, not enforcing the law, so they chose to spend their energy elsewhere.

Why do I point this out? Because South African racial politics are far more complex than the ‘white vs. black’ conflict so often cited by Americans when talking about my home country. Many ‘coloured’ people would be as offended at being called ‘black’ as a Navajo would be at being called African-American.

If you don’t understand that there is more than one group of workers in this situation and that their interests don’t clearly align—there is actually enormous competition for jobs and housing between the ‘coloured’ workers and the recently-arrived Xhosa which “Wine Woes” lumps together under the category “black”—you won’t understand how the situation evolved or how to fix it.

I believe that exposé journalism should provide the reader with actionable information that allows them to improve bad situations, whether by choosing certain products over others, supporting one politician over another, etc.

“Wine Woes” paints the entire Cape wine industry with a particularly dirty brush instead of providing wine drinkers with this actionable information. Readers aren’t provided with the names of abusive wineries or those progressive firms striving to improve working conditions, eliminate pesticide use and conserve endangered wild species (of which there are more and more every year.)

Are ethical wine farmers and the thousands they employ expected to burst into joyful song as they fall into bankruptcy because foreigners have quit buying South African wine under a barrage of bad publicity? Last time I checked no worker was lifted out of poverty because their employer went bust.

The movie embedded in the piece is damaging as well as cowardly—by providing just enough information employers to identify the workers in the film but not enough for consumers or law-enforcers to identify the wineries concerned, the filmmakers protect themselves from lawsuits but lay abused workers open to further victimization.

I’m also not sure what this accusatory piece gains by emphasizing that most South African wineries are “white”-owned and that workers are mostly “black.” Is it trying to say that ‘white’ wine farmers are inherently abusive or that only ‘white’ employers abuse workers? If so, “Wine Woes” should say it clearly instead of hiding behind woolly generalizations. (I find that idea offensive and counter to my own experience; I’ve seen wine industry players of all races striving to improve things and undo the apartheid legacy of racial stratification common to most industries in South Africa (see, for example, here). I can also take Philpott on an unforgettable tour of some “black”-owned gold mines in South Africa where worker abuse extends to murder and makes the wine industry look like, well, a wine-soaked picnic on a gorgeous Stellenbosch afternoon.)

South Africa is a deeply imperfect work-in-progress with a corrupt government, stubborn racial tensions and massive unemployment. It also has millions of innovative, hard-working of people struggling for a better life who need all the help they can get. It would be good of Philpott and his sources to point fingers precisely and carefully at those who deserve to be called out, not place the whole wine industry, and by extension the country, in the same bucket of ordure.

Thousands of families have food on the table tonight because South African wine is “increasingly fashionable” in the USA. For many there’s no choice between a job on a wine farm or a job somewhere else—there’s a choice between a job on a wine farm and no job at all. Let’s not forget that.

note: I’ve used racial descriptors such as ‘black’ and ‘white’ in quotes because I’d like not to uncritically perpetuate the use of Apartheid race categories to describe people while at the same time acknowledge that these labels still have descriptive currency when talking about South African society.

Tom Philpott responds:

I salute Adam Welz for offering his from-the-ground perspective—and for broadening my view and that of my readers on this particular topic.

It is true that as a blogger based in the mountains of North Carollina, I rarely get to visit the places I write about and see with my own eyes the conditions on the ground. For this reason, when setting out to write about some faraway place, I choose my sources carefully. For this post, I was citing an in-depth report by Human Right Watch, a widely respected NGO with decades of experience documenting abuses stemming from power inequalities: precisely the situation that too often holds sway in food production, not just in South Africa but (as I took pains to point out) all over the globe, including right here in the United States. (HRW’s 2005 report Blood, Sweat, and Fear remains the definitive source on working conditions in US meatpacking plants).

Rather than acknowledge the formidable source from which I drew my observations, Welz mostly ignored it in his response. He mentions it only in context of the short video Human Rights Watch released along with its report and which I uploaded to my post; and here, rather than critique HRW’s account of labor conditions in South Africa’s vineyards, Welz rebukes the group for showing the faces of abused workers and leaving them “open to further victimization.” I am left wondering whether he has read the report and what he thinks of it, beyond his complaint that it doesn’t name names of abusive employers. His contribution would have been even more interesting and enlightening if he had seen fit to directly engage the HRW report.

Finally, Welz seems to have misunderstood the intent of my post. I was not trying to engage in “exposé journalism.” I was simply trying to make the point that the wine we drink, like the food we eat, comes from somewhere and is produced by real people on real land. I didn’t mean to tell my readers what to think about wine; just to urge them to think about wine, to learn more.

Welz’s account of what he has observed in South Africa’s vineyards, as well as his discussion of the complexities of race there, is much appreciated in that regard.