T.J. Kirkpatrick/AP Photo

Update (3/18/2013): The US State Department confirms that Bosco Ntaganda has turned himself in to the US Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda. After entering the embassy, the wanted warlord requested a transfer to the International Criminal Court in The Hague. “We are working to facilitate the requests Ntaganda has made,” a State Department spokesperson tells Mother Jones.

Bosco Ntaganda loves a dinner party. Hell, even a brunch party. And pretty much any time of day is perfect at Le Chalet, Goma’s premier restaurant, where the inside is all slate floors and licheche-wood furniture and Latin jazz, and outside tables dot a manicured lawn that slopes down to Lake Kivu. It has what may be the best selection of booze—Blue Label, pastis, whatever you like—in this provincial capital in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. The chicken samosas in curry sauce with pineapple are delightful. And Bosco, a man about town who owns the bar Kivu Light and the Bunyole cheesery, is a fixture here, enough that the first time I walk in, someone says casually, “Oh! You just missed Bosco.”

That’s why one Congolese driver told me he couldn’t take me around Goma because he would be killed the moment I left. That’s why my Congolese sources stay out of nice restaurants, stay out of the city if they can, and when they have to flee the country, they don’t tell their families where they’ve gone or why. That’s why one guy I meet wears a light disguise whenever he goes out (“Oh hey!” an old friend says after initially walking right past him. “I didn’t recognize you!”): Because recently, Bosco tried to kill him.

That’s not included in the official indictment against Bosco. The warrant (PDF) the International Criminal Court issued for his arrest on August 22, 2006, charged him only with the war crimes of enlisting, conscripting, and using child soldiers back when he was head of military operations for a rebel militia in the early 2000s. These days, he’s technically legit, wearing the uniform of a general in the national Congolese army. In 2009, a peace deal (PDF) between Congo and Rwanda folded in the Rwandan-backed Congolese militia he headed, the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), which frankly was kicking the national army’s ass. Both before and since, the ICC and the United Nations and watchdogs like Human Rights Watch have continued to catalog further atrocities he’s alleged to have ordered or participated in: 800 civilians massacred in one town in the Ituri district in 2002; 150 civilians massacred in North Kivu province in 2008; ongoing assassinations and disappearances; ongoing conscription of child soldiers, the very crime he was indicted for. Etcetera.

And that’s why everyone in this dusty, volcano-fringed capital (PDF) talks like spies. “It’s probably best you keep your voice down everywhere all the time while you’re here,” an American aid worker says the moment we meet. “They have people working everywhere,” a Congolese guy tells me, specifically referring to waiters who eavesdrop at bars, saying that when they do you can’t leave because it will look suspicious, so you have to always pretend like you don’t suspect them, so they won’t in turn suspect you. Ex-CNDP soldiers loyal to Bosco are armed and prevalent, in this town of 500,000 and beyond. Consider: This year, when Bosco was implicated in selling $20 million in gold for $7 million in cash to a shady Texas diamond dealer, a Frenchman, and two Nigerians, the regional military spokesperson said it looked like Bosco was smuggling, but really he was just pretending to smuggle to thwart the smugglers. It’s all part of the reason why you’ve never heard of Bosco, why detailed stories about atrocity-witnessing and near escapes and car chases can’t be told for the sake of protecting sources. You wouldn’t believe the opening we had to cut from this piece. It was about a guy who wanted to tell his story to the world in hopes it would change the “hell” he lives in. But then he was cornered by a soldier who reminded him that it’s awfully easy to get killed around here.

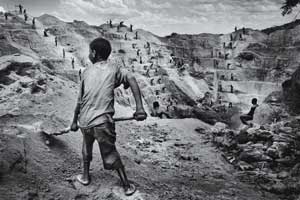

So. Take instead what happened to an American filmmaker, now safe at home. Earlier this year, he took it upon himself to shoot mining operations in Goma’s province, North Kivu. Here’s the thing about that: In 2010, President Joseph Kabila temporarily banned mining in this province and two others, on account of armed groups controlling the mines; an estimated 80 percent of what is mined in Congo is smuggled out, a lot of it from this area on the border with Rwanda. And indeed, there, running the mine (PDF), were officers from the CNDP—sorry, ex-CNDP, since they’ve technically been integrated into the national army and technically don’t operate for their own profit anymore—wearing CNDP uniforms. They were overseeing workers loading coltan (used in consumer electronics) into produce trucks. There, getting it all on camera, the American filmmaker got caught.

Photos: The War On Congo’s WomenHe managed to escape, but word spread through the command, back to Goma, when he returned. “Soldiers followed me all over town,” he says, until he fled to another country. And they didn’t even know he also filmed those women who were raped, and people who were shot by ex-CNDP soldiers now in the national army! His last day in Goma, the filmmaker pushed the furniture in his hotel room up against the door, passing the night barricaded behind it, sleepless, with his eyes wide open and a knife in his hand.

Photos: The War On Congo’s WomenHe managed to escape, but word spread through the command, back to Goma, when he returned. “Soldiers followed me all over town,” he says, until he fled to another country. And they didn’t even know he also filmed those women who were raped, and people who were shot by ex-CNDP soldiers now in the national army! His last day in Goma, the filmmaker pushed the furniture in his hotel room up against the door, passing the night barricaded behind it, sleepless, with his eyes wide open and a knife in his hand.

He was lucky. “Even if you have a gun, it doesn’t mean you cannot die,” one Congolese source told me. “You cannot stop them from killing you.”

Some 4,000 miles away from North Kivu, the International Criminal Court sits in a tall, drab office block rising up against seemingly ever-cloudy Dutch skies. The building at Maanweg 174, The Hague, was previously occupied by a telephone company. Proceedings against warlords take place in three low rooms built into the former parking garage.

The court is slated to get its new digs in 2015; these are the temporary offices of the fledgling institution, which was established in 2002. That’s when the requisite 60 countries ratified the treaty that created it, four years after the 1998 UN Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court—which itself had been years in the making—brought 160 governments together to spend a month fighting out the terms. Not everyone agreed that such a court should exist at all. Leading the haters was the United States, which had grave objections to “an arrangement whereby US armed forces operating overseas could be conceivably prosecuted by the international court.” But in a decade that saw a couple of high-profile genocides, justice was an especially pressing ideal. As the head of the US delegation summed it up (PDF) to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee afterward, the goal was “accountability, namely to help bring the perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes to justice,” via “creating a permanent court that could be more quickly available for investigations and prosecutions and more cost-efficient in its operation.” Supporters wanted to make international justice swifter than the infamously tardy International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and cheaper than the $1.9 billion, still-ongoing International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

Members Only

The International Criminal Court is international, but it’s not global. Only the countries shown in red are legally obligated to execute its arrest warrants. And sometimes legal obligations run afoul of political realities.

The delegates decided that there would be three roads to prosecution: A case could be referred to the ICC by a member state; crimes could be referred to the court by the UN Security Council; or the Office of the Prosecutor could launch an investigation on its own. (Well, not all the delegates decided that. The United States—along with China, Iraq, Israel, Libya, Qatar, and Yemen—voted against the treaty. The US later signed but did not ratify it.) If an ICC investigation finds war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide, and the state in which the crimes occur is unwilling or unable to prosecute the case itself, the “court of last resort” can issue warrants of arrest or summonses to appear.

On this early April day, there are two trials in session—both of Congolese former rebel leaders. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo stands accused of conscripting, enlisting, and using child soldiers in Congo. Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo was arrested for multiple war crimes and crimes against humanity, including rape, torture, and pillaging in the Central African Republic. In the case of Lubanga, today’s testimony is too sensitive to be opened to the public—maybe a witness who’s in particular danger of retribution. But anyone can observe Bemba’s trial (PDF). Between the two prosecutors on the right, two defense lawyers on the left, and three judges sitting center, there are a lot of black robes in the room. Observers listen to testimony via a UN-style translation system. Bemba’s in a suit under guard in the corner; the witness chair is oriented so he can’t look squarely at the person testifying. I know Bemba came to check out his troops, the witness is saying. He knew what his troops were doing. The witness is kind of worked up. The soldiers were raping and looting, he’s saying. Bemba must have known what was happening. For his part, Bemba has got his cantaloupe head sunk into burly shoulders. He’s looking impassive, sometimes taking notes, licking his fingers to turn the page, flicking his eyes again and again toward the observation gallery just a few feet away, but refusing to meet anyone’s gaze.

A child soldier north of Goma, 2008 Marcus Bleasdale/VUpstairs, Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo has his sleeves rolled up behind the desk of his expansive office on the 11th floor. In the ’80s, he prosecuted mass-murdering military commanders in his native Argentina. In the late ’90s, he was the star of an Argentine show very much like Judge Judy. He’s grayer now, but still brash and deep-voiced and having an answer for everything. And, for a guy who spends all of his time thinking about war crimes, he has some very happy things to say.

A child soldier north of Goma, 2008 Marcus Bleasdale/VUpstairs, Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo has his sleeves rolled up behind the desk of his expansive office on the 11th floor. In the ’80s, he prosecuted mass-murdering military commanders in his native Argentina. In the late ’90s, he was the star of an Argentine show very much like Judge Judy. He’s grayer now, but still brash and deep-voiced and having an answer for everything. And, for a guy who spends all of his time thinking about war crimes, he has some very happy things to say.

“We are building a new global system,” he informs me. He says the idea that so many countries came together to build this court is insane. The fact that they managed to arrest someone is ridiculous. That they had a first trial was “impossible.” And now, the world is getting smaller. Technology is bringing us closer. Facebook, goddammit. “Cambodia was ignored. Nothing happened. Darfur was not ignored, but took two years to react. Libya? Ten days. Ten days. Bam. And the Security Council, immediately, without hesitation: ‘Refer the case to the ICC.’ Now we’re normal.” He tells me about an Australian fighter pilot who wouldn’t drop a bomb in Iraq because he was afraid of someday being prosecuted. He says a legal adviser told NATO commanders to watch the orders they sign so they don’t end up retiring on the beach only to be surrounded by cops ready to drag them to The Hague. Nepal, he says, demobilized 3,000 child soldiers because of the ICC.

“The court’s existence is important. The message is pretty strong: You cannot commit massive atrocities to remain in power or to gain power,” Moreno-Ocampo says. In the case of Bemba, his arrest probably did teach warlords a lesson about whether they can retire or vacay in Europe, as he was snatched by Belgian authorities while comfortably ensconced in Brussels. Although 44 UN member states have still not signed the Rome Statute, the ICC has 700 staff members from 75 countries. The more countries that are on board, the more the world manages to “create one community called humanity,” the more effective the court can be. “Everything is changing in the world. We can do it.”

Moreno-Ocampo has sunk 10 years of his life into the ICC, separated from his home and his own life and his family. Because “it’s the best job in the world.” Because “I love this mission, to save the world.” Also: “It suits my megalomania.”

That makes him well suited to weather scathing criticism, and does the ICC ever have its share. Those who say that issuing arrest warrants for war criminals still in the throes of warmongering—as in the case of Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir—complicates the peace process and could even incite more violence. Those who complain that the court only goes after Africans, which so far has been true. That the first trial, Lubanga’s, has had disastrous flaws, including the prosecution’s failing to share key documents with the defense. That as an independent court, accountable to no other body, the ICC operates with impunity.

But the issue that could most undermine the very purpose of the court’s existence is its difficulty executing arrest warrants. As a court representative will explain if you sign up for an ICC visitor’s tour, “We don’t have a police force. So when it comes to enforcing our warrants, we rely on state parties.” That means countries that have ratified the treaty, like Congo; all of them are technically obligated to arrest indicted criminals on their soil. Yet out of 26 people for whom warrants and summonses have been issued, 10 of the alleged criminals remain at large. None of the three outstanding warrants (PDF) against Ugandans have been enforced, even though Uganda is an ICC party—but that’s because, the tour guide offers as explanation, the guys are hiding in the no man’s land near the border between Congo and the Central African Republic. When Sudanese President Bashir flew from (non-member-party) Sudan to (member-party) Kenya, he should have been arrested; if he goes into international airspace again, the rep asserts, he will be.

I ask Moreno-Ocampo if it’s only a matter of time for Bosco Ntaganda, too. “Yeah,” he says. “In fact, it is difficult to arrest Bashir, I understand, but it’s not difficult to arrest Bosco. There is no excuse not to arrest Bosco. And he’s committing massive crimes in the DRC.”

The World’s 6 Most Feared War CriminalsThis is the part of a paragraph that would usually contain a description of a room, in a (adjective here) building on (this kind of) a street. But I can’t write about any of that. Nor could I bring any Congolese translators along to this interview—the risks to them and the witnesses would have been too great. So I’ve dragged a 22-year-old Columbia University student and fluent French speaker named Joey from the United States.

The World’s 6 Most Feared War CriminalsThis is the part of a paragraph that would usually contain a description of a room, in a (adjective here) building on (this kind of) a street. But I can’t write about any of that. Nor could I bring any Congolese translators along to this interview—the risks to them and the witnesses would have been too great. So I’ve dragged a 22-year-old Columbia University student and fluent French speaker named Joey from the United States.

Joey and I are at the indescribable place to hear a story. It’s about Lt. Colonel Antoine Balibuno, a colleague of Lt. Colonel Innocent Zimurinda, a terrifying Bosco crony who’s been sanctioned by the UN for raping “a large number” of women and girls and murdering a lot of refugees and his own child soldiers. In 2009, Balibuno and Zimurinda were together in Masisi, a few hours from Goma, under Bosco’s command. But Balibuno and Zimurinda had also been integrated into the national army, deployed to the region officially. Not so lucrative a position, working for the broke army of a failed state. Masisi had a lot of trees. Balibuno told friends that Zimurinda enslaved the locals, making them cut down trees, morning and night, to make boards the ex-CNDP could sell. Balibuno said those who resisted were immediately killed. Balibuno said Zimurinda, a Tutsi, was also killing random Hutus. After a while, Balibuno returned to Goma, claiming he didn’t want to be associated with any Bosco-related carnage and corruption in case Bosco took his colonels down with him if he ever did get arrested.

The men telling Joey and me this story are three of Balibuno’s friends. Balibuno called one the night of September 14, 2010. “He wasn’t talking to me, but the call was still open,” the friend remembers. “I heard him yelling, ‘Where are you taking me? You told me that we were going to a dancing club. Now we’ve just passed it. What are we doing here? Now there’s a military jeep full of soldiers in front of us, blocking the road. Tell me if you’re going to kill me. Tell me if you’re going to kill me; we didn’t agree on this. I’m not okay with this. I didn’t tell you I wanted to go to Bosco’s. If you want to kill me, tell me so.’ Then the call cut. I called back. It rang; no one picked up. I called back again. It didn’t go through.”

Children internally displaced by the 2008 Kiwanja massacre, carried out by the CNDP while Bosco was military chief of staff Photo: Sarah ElliottBalibuno’s friends weren’t surprised when his body was found outside a restaurant with bullets in the chest, neck, and head. They knew his failure to pledge loyalty to Bosco, his walking away from Zimurinda, was trouble. He’d been claiming for months that Bosco’s men were arranging his assassination. Soon, soldiers came looking for Balibuno’s friends, too, because they’d given testimony to local military officials. There was evidence to suggest who’d killed him—men who were, in fact, staying with Bosco. But when the military commander of the region sent soldiers to arrest the assassins at Bosco’s house, other soldiers loyal to Bosco turned them away.

Children internally displaced by the 2008 Kiwanja massacre, carried out by the CNDP while Bosco was military chief of staff Photo: Sarah ElliottBalibuno’s friends weren’t surprised when his body was found outside a restaurant with bullets in the chest, neck, and head. They knew his failure to pledge loyalty to Bosco, his walking away from Zimurinda, was trouble. He’d been claiming for months that Bosco’s men were arranging his assassination. Soon, soldiers came looking for Balibuno’s friends, too, because they’d given testimony to local military officials. There was evidence to suggest who’d killed him—men who were, in fact, staying with Bosco. But when the military commander of the region sent soldiers to arrest the assassins at Bosco’s house, other soldiers loyal to Bosco turned them away.

Balibuno’s friends ran. They’re now far away from home, separated from their families and out of work. They are desperate. They think their families might be slaughtered. They don’t have any money. If they are found today, they tell us, they will die today. They can’t talk to the government because the government has turned a blind eye to Bosco since the peace deal. They emailed the ICC to tell them they want to testify because it’s impossible to get help from their own government. Lots of people are hiding like this. Lots of people have fled Goma. Please could I give them money so they can pay rent? Actually money for rent will only sustain them in the short term, so please can I find a way to relocate them to another country? Even if I’m just a journalist, maybe I have friends or contacts who can evacuate them. As long as they stay in this country they will have to hide.

“You’ll never be able to live freely in Congo?” I ask.

“If they arrested Bosco,” one of them replies instantly, “I’d go home.”

For now, they’re going back to the tiny place they share. We stand up when they stand up, and they immediately tell us to sit back down. Wait for them to leave, they say. Let them leave first, in case there are men outside waiting to kill them. They file out one at a time—without saying a word to each other—each waiting a few minutes after the one before so that if an ambush is there, only the first will be killed and maybe the others can escape.

The last witness out puts this face on before he exits, sort of a deep-breath, head-up, resolved-but-fearful look as he makes his way toward the door. Shortly before, he’d lamented Congo’s policy of integrating former warlords into its national army in the interest of everyone getting along. Congo’s minister of communications has said that the government prioritizes peace over justice. In addition to reigning over the former CNDP, Bosco is a friend of the Rwandan government, and it’s imperative that Rwanda stays an ally, since it went to war with Congo twice in the ’90s. “What does that mean?” the witness asks rhetorically. “It means people can die, but Bosco will always stay in power.”

For the last few years, with foreign donor money and partners like the American Bar Association, Congo has been working to mitigate its history of impunity by finally trying some war criminals. It currently runs itinerant courts that travel to remote spots to talk to victims of rape and other atrocities. One mobile court official whose name can’t be used or likeness described—you see the theme here—has worked on dozens of such cases, and wishes Bosco were one of them. But he knows what impunity looks like better than almost anyone: Sometimes when ex-CNDP soldiers are arrested, a bunch of other soldiers come to the jail with guns and demand them back. “These crimes [Bosco’s] done are inexplicably horrible,” the official says when I meet him. “If we could, I would arrest him.”

This judicial official performs one of the most dangerous jobs in the country from a filthy office with ripped couches. Though any conviction is a real milestone here, some experts argue that the government is going after only smaller fish. If anyone ever does arrest Bosco, the official says, he’s ready to assist in the prosecution. They’ve got some files on him that would give you nightmares. “The ICC listed only a few reasons on the warrant. We could arrest him for many more.”

“So why aren’t you guys arresting him?” I ask.

“I can’t say it directly. As we’re working for justice, there are always people working in the opposite direction.”

“Are you talking about people in the government, like President Kabila?”

“In the name of peace, I have to keep it a secret.”

Being this vocal about justice does not make the judicial official’s life easier. He’s had plenty of threats on his life. “I left my house,” he says. When I tell him he has giant balls to keep coming to work and keep his composure, he says simply, “No one can know that I am ever afraid.”

“We want zero tolerance,” he says, and Kabila has stated the same. The official says that overall, “What we ask of the world is to help us have the authority of the state, in all corners of the forest.” He walks Joey and me out, and we emerge into the blazing sunshine. He squints while he shakes our hands, and though I can feel his palm and fingers warmly, hugely enclosing mine, I have the weird feeling that it’s not really happening—a reaction, I suppose, to my understanding that the human currently touching me is pretty likely to be murdered.

Before the witnesses ended up in the place that can’t be named, they sought refuge from a very manly sounding acronym: MONUSCO. The United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is a peacekeeping force nearly 25,000 strong, a whole massive international ICC-cooperative army. It’s headed by Roger Meece, who’s from the United States, which picks up the largest share of its cost—$1.37 billion between July 2010 and June 2011.

Meece was out of town when I was in Congo’s capital. But his No. 2, Leila Zerrougui, and her special assistant, Francesca Jannotti Pecci, received me in a cool office in the UN’s Kinshasa compound.

“For us,” Zerrougui explained, “the most important issue that we have to address—because it’s the high-profile issue that attracts interest—is the protection of civilians.” (They will not comment on why they only protected Balibuno’s friends for a month.) The second, and sometimes competing, priority of the mission is to get rid of rebel groups by supporting the Congolese army’s operations against them.

“You cannot imagine the time that we spent to screen the commanders that we work with,” Zerrougui says. “You cannot imagine the time that we put in to make sure that we will not work with people that could put the population at risk. It’s the government of the DRC who decides to have an agreement, to integrate a former armed group in the national army. We are not an occupying force. We are a force that is in support of the government—that is sovereign, that has its own institution, its army, etc.” And though there’s not as much improvement in places like Masisi, Zerrougui says, all in all there are big improvements in regional security. She laments that “people are always talking about what is not done.”

Guilty! “Are you guys going to try to arrest Bosco again?” I ask.

“What?”

“Are you guys going to try to arrest Bosco again?” The UN force in Congo attempted to apprehend him once, several years ago, before the peace deal, but the commander of the arresting force reportedly lost his nerve.

“If the government would like to arrest Bosco, we are here to support the initiative taken by the government.”

“Well, but I mean the government did request that.” Years ago, the Congolese government wrote a letter to the UN mission in Congo formally requesting that it arrest Bosco. That was back before he was integrated into the national army, though, Zerrougui says.

But they never formally rescinded the request, I say; so they would have to ask again for MONUSCO to arrest him?

“Why are you expecting MONUSCO to do that?” Zerrougui asks me. “Why are you not asking this question to the government?”

Well, I tried. Nobody in Congo would answer my questions, but eventually I heard from the DRC’s ambassador to the United States, Faida Mitifu: “We are not protecting anyone who has committed crimes against humanity. But at the same time there are certain priorities one has to make in the name of peace, and in the name of putting an end to the humanitarian crisis, it was a choice between the bad and the worse. So we chose the bad.” That might not satisfy Jason Stearns, formerly the coordinator of the UN’s Group of Experts on Congo and author of Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa. “Some people think that arresting Bosco would unravel the peace deal between Congo and Rwanda,” he says. “I think that that’s not true. You could certainly make a case that arresting him could be stabilizing.” He’s divisive within the former CNDP. He’s become an incredibly powerful mineral smuggler, the cause of much of Congo’s conflict. Also: “He’s a living insult to international justice, and the fact that he wines and dines next to the largest peacekeeping mission in the world in full sight? And everybody knows where he is, and logistically speaking, he would not be very difficult to arrest.”

Foreign diplomats are not, Stearns says, “pushing the envelope” nearly as far as they could—”which is typical of diplomacy in the region.” Foreign aid makes up an estimated 50 percent of Congo’s budget, so foreign governments have plenty of leverage were they interested in wielding it. But instead, they “don’t get too involved, even if by not getting involved serious offenders remain at large, because by getting too involved, that increases your responsibility for whatever happens.” True, the conflicts in this huge country are transnational and extraordinarily complicated, and observers fear that the peace is tenuous. Also, there’s China, which has a $9 billion mineral deal with Congo—and, just in case, is looking to increase military cooperation with Rwanda. “I sympathize with the UN, to be honest with you,” Stearns says, but “they can do more.”

Those are the politics. As for the legal issues, I put them to Zerrougui and Jannotti Pecci in Kinshasa. “The people at the International Criminal Court apparently are of the opinion that legally MONUSCO could arrest Bosco,” I say.

“That’s not true,” Jannotti Pecci says. “I mean, it’s subject to interpretation.”

“We have so many things to do here,” Zerrougui says, “that are extremely important for the DRC and for the people of the DRC, and I don’t think that we can just decide what is our priority. If the Security Council decides that we have a mandate as a priority to go and arrest Bosco, then we will certainly do it.”

Because of the courts they’ve been setting up, the trials like the ones the anonymous judicial official has been working on, human rights violators are getting arrested, tried, sentenced. Not all of them—not, say, the officer who’s been accused of commanding his troops to rape and machete young girls—but some, and that’s a great stride. “I understand that one who’s indicted by the ICC should not continue to enjoy impunity,” Zerrougui says. But MONUSCO collaborates with a government and an army that has alleged war criminals in it, yeah. If stability weren’t important, former Nazis wouldn’t have been integrated into the civil service to help govern post-World War II Germany. And think of how long it’s been taking America to heal the wounds of our own civil war, which lasted only four years, had only two sides, and ended with a clear victor. “This is the reality we have to work with,” Zerrougui says. “And we try to influence in the best way, because it’s the only way to ensure that we won’t continue in an ongoing conflict situation for years.”

Bosco’s colonels don’t necessarily seem scary when they’ve got Tommy Hilfiger polos on and glasses of Chivas and Coke in their hands. When I meet one, Seraphin Mirindi, at the Hotel Mbinza bar, he’s reserved, slight, and smiles politely at the appropriate times. Although, when I order the same thing he’s having, to be simpatico, he says something that makes me paranoid.

“I think she usually likes her whiskey straight,” he tells Joey in French.

And I say it like I’m impressed and delighted that he’s got my number when I respond, “Ha ha, how do you know that?” but really I don’t know if he means, “Anybody can tell this chick drinks her whiskey straight,” or “I know for a fact she drinks her whiskey straight because someone’s following her.” I don’t feel better about it either way when he answers me expressionlessly, “I’m not a prophet.”

We’re here because Mirindi is in Bosco’s inner circle, as a spokesman for ex-CNDP soldiers, and since I didn’t run into The General at Le Chalet, I’m requesting an audience. I’ve brought Joey; Mirindi’s brought Lt. Colonel Munyakazi Dieudonné.

Mirindi kicked off our meeting with a spectacularly long-winded and boring history lesson. Among the highlights: the First Congo War in the late ’90s, when rebel leader Laurent Kabila overthrew President Mobutu and renamed Zaire the Democratic Republic of the Congo; the soon-to-follow Second Congo War, in which eight African nations and countless rebel groups battled over Congo’s vast minerals, and millions were killed; the postwar strength of the CNDP, led by Laurent Nkunda and backed by the Rwandan government; the peace deal between Congo and Rwanda that integrated the CNDP into the national army, had Nkunda turned in by the Rwandans and arrested, and saw Bosco Ntaganda handpicked by the Rwandans to take Nkunda’s place as general. “How can we compare what he’s accused of and what he’s done for his country?” Mirindi asks when I add Bosco’s ICC indictment to the story. General Bosco Ntaganda is the peace-glue holding this country together, Mirindi says. He also insists several times that Bosco is 10 feet tall.

“General Bosco is so happy you’re here,” he tells me. “He’s so glad you’re interested in Congo, and he really wants to meet with you.” He says maybe we can all go out dancing. He’ll let me know. Then they give me a very thorough rundown of the financial woes of a Congolese soldier who makes only $55 a month. For that kind of money, it’s impossible to be a patriot with the love of your country at heart. For that kind of money, you do whatever you have to do to make more on the side.

When Mirindi comes to our next meeting several days later, I’m not surprised that he arrives without Bosco, who he said might be joining us. Area researchers, experts, and aid workers agree that though the warrant hasn’t put the fear of God in Bosco, it has instilled a wariness of foreigners, any of whom could be ICC spies. At our second meeting, Mirindi relays the same strange pleasantries on Bosco’s behalf—”He would love to meet you!”—but says he was called away from Goma on business. That may or may not be true; he said that about the other day, too, when I know for a fact Bosco was in town.

He’s all over town, actually, with his empty eyes and his cheeks smooth and fat as a baby’s. We see his truck, which rolls with a small pack of bodyguard/soldiers in the back, driving down Boulevard Kanyamuhanga in the center of town, but lose him in traffic when we give chase. We frequently pass the location of his hotel. A foreign (read: less likely to be murdered) aid worker volunteers to drive us to his lovely house. It doesn’t look like he’s there—no convoy parked out front, just a few soldiers milling around outside. And who can say if the motorbike that starts instantly following us is really following us? And who can say if it’s a coincidence that when we go to a restaurant to lose our possible tail, there’s a truck full of soldiers waiting outside by our car when we come back out? And that they pull out when we do?

Paranoia all around. The next day, a driver almost tosses me off the back of a motorbike while executing a hard skid to turn around because he thinks some soldiers are stalking us. “I gotta get the fuck out of here,” Joey tells me that morning at breakfast; he’s having nightmares about Mirindi and his men coming to find him. And as for Bosco, people think he’s more worried about leaving witnesses around since the ICC indictment. Human Rights Watch strongly believes that he recently disappeared a man who told researchers that Bosco murdered his sister. His men recently threatened some UN peacekeepers; several years ago, his troops allegedly killed one. He switches cell phone numbers constantly. On our last night in town, I decide to give him a call directly, my last resort for acquiring comment. Even though I got the number from a guy who had a meeting with him just days before, a recorded woman’s voice politely informs me in French that the number is out of service.

“They can, yeah,” Chief Prosecutor Moreno-Ocampo tells me the next time I see him. We’re at the Mercer Hotel in New York, which has funky purple leather chairs. I’ve just asked him whether MONUSCO can legally arrest Bosco Ntaganda.

“They can,” I repeat after him.

“Yeah.”

“MONUSCO’s position now is that they can’t arrest him because the government would have to ask again, and so if they arrested him without the government asking, it would be against the mandate. You’re shaking your head.”

Silence. The prosecutor scowls. Eventually, he says, “This is new for me. I…I…” He pauses, and there’s silence again. “I was thinking the mandate was clear, the request was clear.”

“That they should arrest him.”

“Mmm-hmm. Because the mandate is they can assist the government in arrest, and the government requested that they arrest him. So.”

“But that was a while ago.”

“Yeah, but there’s no letter saying not to arrest him.”

The ICC’s official line on Bosco Ntaganda is that Kabila will arrest him eventually, and that the UN and the rest of the international community need to pressure him to do so. So MONUSCO saying they’re legally, definitively just not allowed sounds a little buck-passy. When I tell Moreno-Ocampo he seems unhappy—in that he’s glaring at me furiously—he says, “I am. Because I think it’s a big shame that Bosco hasn’t been arrested, and then, I figure we should do better.” Moreno-Ocampo repeats often that one of the keys to international justice is consensus among the players, and he considers it his job to create it. “So. Yeah. Because if we are not doing all the things we can do…I have to focus on that. I have to focus on that, and I’m totally pressured to do that. See because…” Rough throaty exhale. “Fuck.”

When I ask him if Bosco sashaying around Goma next to that big expensive peacekeeping force is making international justice look bad, he says, “It’s easy [to arrest him]! I agree with you! Bosco’s just a matter of will.”

“It’s a matter of will,” he repeats. “That’s the point. In all these issues, it’s a matter of will. If you live in the Kivus, you are full of fear of Bosco—you have fear that you could be killed or raped or looted. It’s not life. My clients out there are the people who live in the Kivus. And my way to protect them is to arrest the leaders who are committing the crimes.” He says again that they can do better. He says again—five times—that it’s only a matter of will. On the recording of this interview, he says many of these things over the sound of his knocking something agitatedly against the table.

It’s the base of a champagne glass. It’s after 9 p.m., and the Bellinis were ordered a half-hour ago. It’s been a long day. I started shadowing Moreno-Ocampo at 8 in the morning, when he was in Chucks and jeans and finalizing the statement he was about to make to the Security Council on the Libya investigation they’d asked him to undertake. It was difficult but important, he told me as he tapped on his MacBook, to get people passionate about law: “When the world is divided, criminals profit.”

And he and the ICC staffers in New York were excited about this speech! A situation like Libya, after all, is why the ICC was conceived, why now 116 member nations entrust the institution with the power to prosecute war criminals, to deter aspiring ones, to issue arrest warrants when a guy like Moammar Qaddafi launches a war against civilians. That morning, Moreno-Ocampo told the assembled council (PDF) that the international community would have to cooperate in making the arrest. A new world of action, a new frontier of never again. He quoted UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon: “Now we have the ICC, permanent, increasingly powerful, casting a long shadow. There is no going back. In this new age of accountability, those who commit the worst of human crimes will be held responsible.”