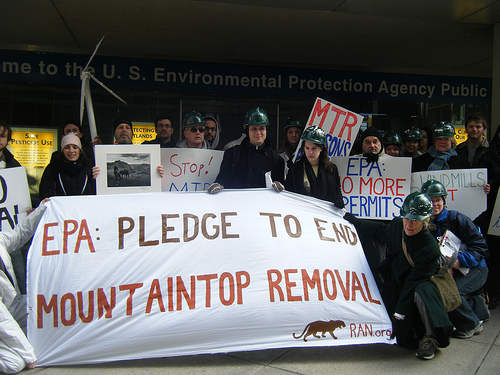

nrdc_media/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/nrdc_media/2964379829/">Flickr</a>

Last month, when coal execs read the report linking birth defects to mountaintop removal mining, they weren’t exactly thrilled. One rebuttal, penned by four attorneys with the firm Crowell & Moring, which represents the National Mining Association, accused the study’s authors of using cherry-picked and misleading data. But that apparently wasn’t convincing enough, so they went a step further and employed a discredited stereotype about inbreeding in West Virginia.

“The study failed to account for consanquinity [sic], one of the most prominent sources of birth defects,” the attorneys’ statement said. It then went on to advertise the firm’s services to coal companies looking to “counter unfounded claims of injury or disease” from potential lawsuits sparked by the study.

The statement, which had been on the firm’s website for more than a week, was quickly removed yesterday after Charleston Gazette blogger Ken Ward Jr. pointed out its insinuation that inbreeding hicks, not mountaintop mining, were to blame for spikes in the rate of birth defects, which it also said didn’t exist in the first place. Wrap your head around that one. (Thanks to Ward, you can still read the statement here.)

Ward asked one of the study’s co-authors, West Virginia University’s Michael Hendryx, to weigh in. His response:

The criticisms raised are to be expected. I disagree that we overstated our findings. I think we’ve been appropriately cautious in what we say about limitations of the study and conclusions. This paper can’t be considered in isolation but should be taken with the more than dozen other studies that continue to document serious health problems related to mining.

The four lawyers didn’t get back to Ward, but a spokeswoman from the National Mining Association did, telling him that she didn’t think anyone was really implying that a failure to look at inbreeding rates discredited the study. Maybe not, but the incident certainly won’t sit well with opponents of mountaintop removal mining in Appalachia.