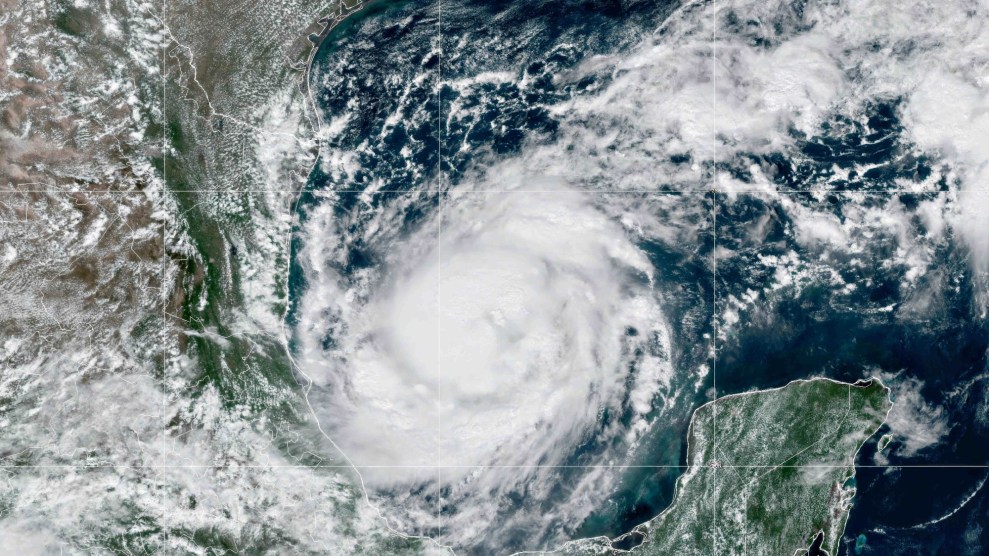

Hurricane Milton is moving across the Gulf of Mexico towards Florida.Goes-East/Noaa/Planet Pix/Zuma

This story was originally published by Slate and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Hurricane Milton has rapidly intensified from a tropical storm to a Category 5 hurricane. This happened in just over 24 hours—it’s one of the fastest rates of strengthening ever observed on Earth. Meteorologists have even begun to speculate that Milton could approach the theoretical maximum intensity for a hurricane in the Atlantic basin of 195 mph, challenging the record set by Hurricane Allen in 1980.

In response to Milton, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is directing millions of people to leave their homes and head to safety—the state’s largest evacuation since Category 5 Hurricane Irma in 2017.

Milton is expected to make landfall just north of Tampa Bay, its powerful wind and waves fueled by record-hot Gulf of Mexico waters. Though Milton could weaken or end up striking elsewhere, the track it’s currently on is remarkably similar to the 1921 Tampa Bay hurricane—the most recent major hurricane to make landfall in that specific region.

This all comes just on the heels of Category 4 Hurricane Helene, which struck Florida at the end of September. Though it made landfall considerably farther north, it produced “several million cubic yards” of storm debris in the Tampa region. Thousands of beachfront shops and homes were damaged, and the wreckage was jumbled together by record floodwaters. Now, Milton’s approach is creating surreal scenes: Tampa Bay Times reporter Max Chesnes posted a video to X showing one side of a street with piles of debris from Helene. On the other side was a blocks-long line to pick up sandbags to prepare for Milton (sandbags can help block water).

Whether Milton will play out this exact worst case scenario is to be seen—but it is currently poised to be very, very bad either way.

Though it wasn’t a direct hit, Helene was still the worst hurricane the Tampa Bay region has experienced in more than 100 years and added to the damage done by Category 1 Hurricane Debby earlier this year. That already makes for a hellish hurricane season in Florida. But the worst could still be yet to come with Milton.

As of Monday morning, Milton’s peak storm surge forecast by the National Hurricane Center for Tampa Bay was 8 to 12 feet, and almost surely will be revised higher. That would double Hurricane Helene’s record-setting water levels. It would also eclipse the surge the region faced in the 1921 hurricane.

That Tampa has gone more than 100 years without a Category 3 or greater landfall is a coincidental fluke not lost on regional planners. Four years ago, Tampa-area municipalities did a tabletop exercise to simulate the response to a hurricane eerily similar to Milton, called Hurricane Phoenix.

The fictional Hurricane Phoenix even had its own terrifying cinematic trailer, created by the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council:

According to a 10-year-old estimate by Karen Clark and Co., a Boston-based catastrophe modeling firm, a direct hit on Tampa Bay by a Category 5 hurricane could produce upward of $175 billion in damage and potentially kill thousands—a Hurricane Katrina–scale disaster, or even worse. And that’s just on its own.

But this hurricane isn’t even happening in isolation. The one-two punch from Helene and Milton is what climatologists call a “compound event.” With little to no time to prepare between landfalls, human misery becomes greater than the sum of the two storms separately. It’s something that was highlighted as a symptom of climate change in the most recent National Climate Assessment published by the Biden administration last year. As sea level rises and floods become more frequent, folks in Tampa are already fearing the effect of a further rise in housing costs that this year’s storm season will likely bring.

Driven in part by the decades-long streak of good luck with hurricanes—the bulk of the damage happening elsewhere in the state—urban west-central Florida has rapidly expanded. Over the past 50 years, the Tampa–St. Petersburg–Clearwater metro area added nearly 2.5 million people, a growth of 187 percent.

A century’s worth of frantic beachfront development led to irrational choices, the epicenter of which is low-lying Pinellas County. A million people live there, crammed into a narrow peninsula jutting into the Gulf and encompassing a chain of 11 barrier islands. If Milton hits as currently forecast, Pinellas County will never be the same.

Tampa Bay’s ocean bathymetry makes the region uniquely vulnerable to the effects of a direct hit from a hurricane. The shallow estuary acts to funnel flood waters into the bay, making the metro area one of the most at-risk places in the world for storm surges. Though the current forecast is lower for now, in theory, a worst-case major hurricane landfall like Milton could cause 20 or 30 feet of storm surge, on the order of Hurricane Katrina. A direct hit by a Category 5 slightly north of Tampa Bay would maximize the amount of storm surge; if—when—such a situation occurs, it is projected to be the most expensive natural disaster in U.S. history. Whether Milton will play out this exact worst-case scenario is to be seen—but it is currently poised to be very, very bad either way.

The reality of climate change is bad enough without late-stage capitalism and MAGA making it worse. For folks in Milton’s path, the Centers for Disease Control maintains a disaster distress hotline if you need someone to talk to.