Palestine Peace Not Apartheid. The title was Jimmy Carter’s idea. Peace talks were nonexistent, Israel showed no sign of ending its control over the lives of millions of Palestinians, and the United States was not doing anything to stop it. Carter wanted to be provocative. He succeeded.

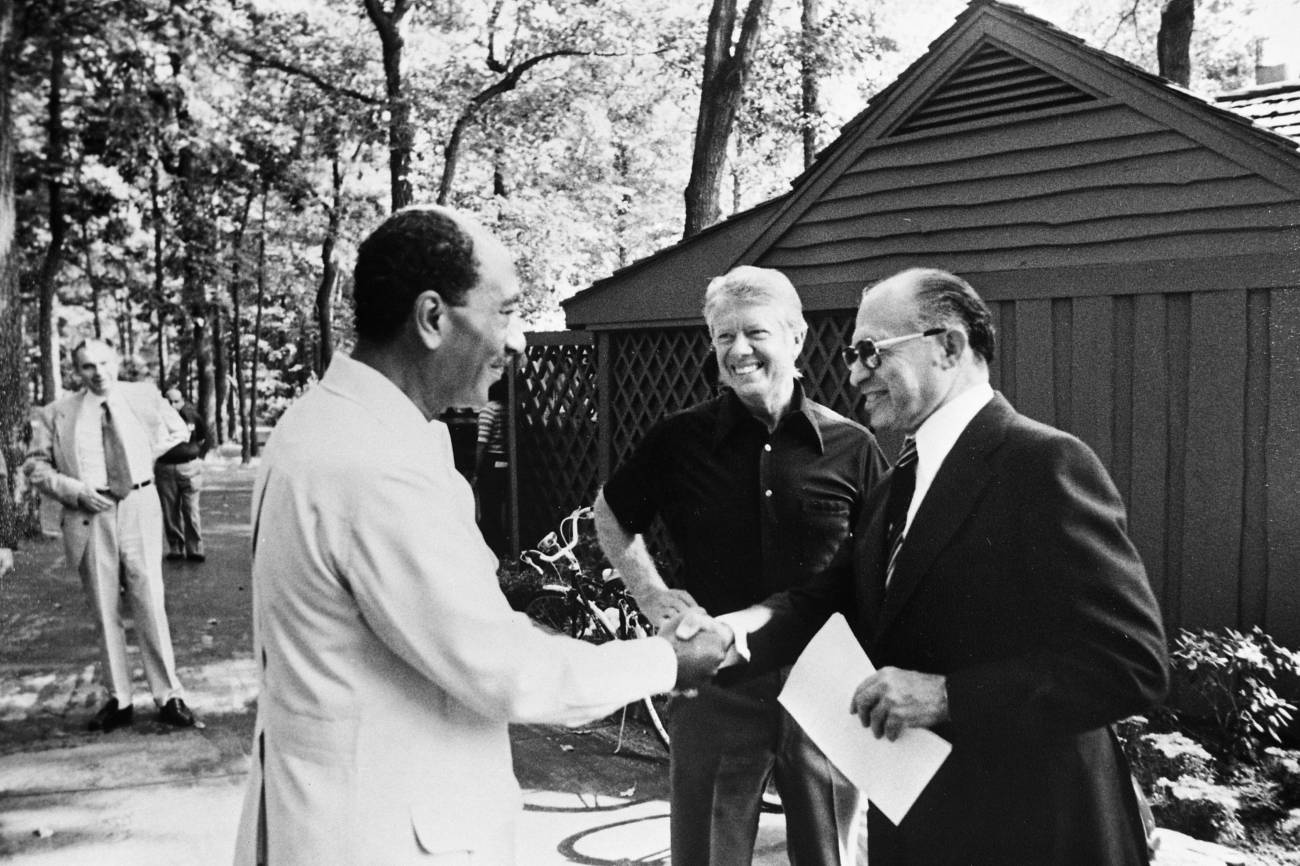

The well-organized backlash to Carter’s 2006 book was captured by an ad in the New York Times from the Anti-Defamation League that declared: “There’s only one honest thing about President Carter’s new book. The criticism.” Included below were denunciations from Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.), incoming House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and DNC Chairman Howard Dean. Carter, who’d brought together Israel and Egypt at Camp David in 1978 and won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2002, said he was being called a bigot and an antisemite for the first time in his life.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat (left) and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin (right) shake hands at Camp David in 1978, as President Jimmy Carter looks on. Carter

Imago/ZUMA

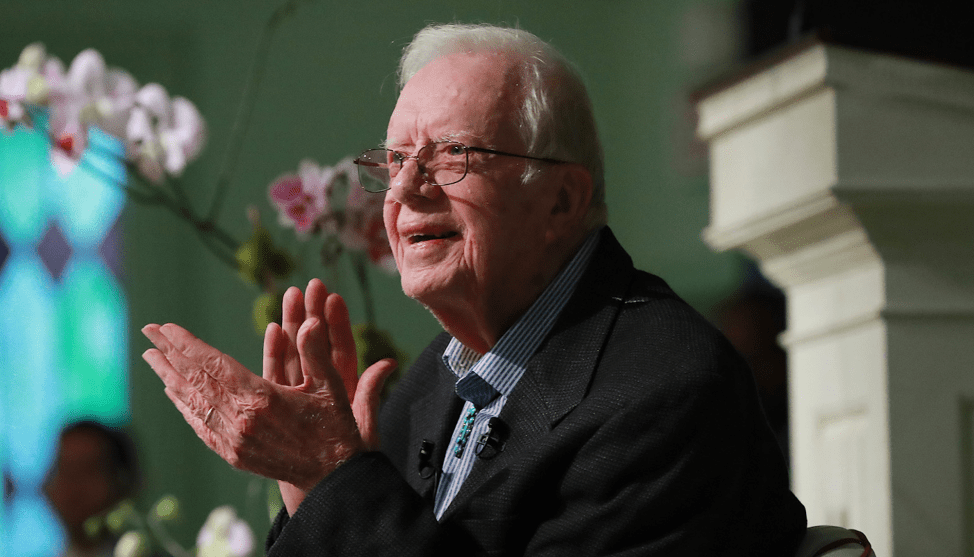

On Sunday, December 29, the 39th president of the United States died at the age of 100. Eighteen years after it was published, Palestine Peace Not Apartheid is representative of an essential part of his legacy. Carter saw where Israel was headed with its refusal to countenance Palestinian statehood, and correctly warned it would end tragically for both sides. In response, the American mainstream treated him as a crank at best and an antisemite at worst. With Palestinians now suffering the worst violence in their history, which Amnesty International recently concluded constitutes genocide, it is more important than ever to recognize the truth of Carter’s claim that peace would only come when Israel—likely under pressure from the United States—abandoned its efforts to deprive Palestinians of sovereignty in their homeland.

The heart of Carter’s argument was that Israel has faced the same choice for most of its history. In exchange for peace, it could return the land it began illegally occupying after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. That path would leave Israel with about 78 percent of what was once Palestine, while Palestinians would have control over the remaining 22 percent in Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the West Bank. Alternatively, Israel could try to take everything, thereby forcing millions of Palestinians in the occupied territories to live under a system of apartheid. Carter saw that Israel was taking the second path but felt that it was not too late to pull back.

Sadat, Carter, and Begin sign the Camp David Accords in the East Room of the White House on September 17, 1978.

Arnie Sachs/CNP/ZUMA

Palestine Peace Not Apartheid was a short book. Anyone, whether they know a little or a lot, could follow Carter’s argument and understand why he was appalled. If anything, Carter went too easy on Israel. Like many American liberals, he was intent to draw a distinction between Israel’s actions on its side of the so-called Green Line and what it did beyond it in the occupied territories. When Carter looked at a map of Israel and the West Bank, he saw democracy on the left and apartheid on the right. He didn’t stop to ask if one society could inflict such a plague on another without being deeply ill itself. With Israel now run by a far-right government that includes proud bigots in senior posts, it is clear the answer was no.

The reaction to Carter from the mainstream media can be divided into two main camps: critics who read the book and critics who almost certainly didn’t. The latter group asked Carter about the part they had absorbed: its title. Why use such an inflammatory word? Wasn’t it counterproductive? No, Carter said over and over in the interviews he sat for during the book tour. He believed that apartheid, with its evocation of white South Africa, was more than fair.

In some respects, the oppression faced by Palestinians was more severe in his view. “If you go to Palestine to see what’s being done to the Palestinians, their land completely taken away from them, all of their basic rights taken away from them, they have to have passes to go anywhere,” Carter said on PBS. “I would say, in many ways, it’s worse than the treatment of Black people in South Africa under apartheid. It’s worse.” (The Israeli human rights groups B’Tselem concluded in 2021 that Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line live under apartheid; Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch both use the term as well.)

The critics who had read the book mostly treated Carter with exasperated condescension. In the Washington Post, Jeffrey Goldberg, who served in the Israeli army and is now the editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, labeled it a “cynical book” with a “bait-and-switch title” before arguing that Carter was wrong to focus so heavily on the settlements Israel was illegally building in the West Bank:

The settlement movement has been a tragedy, of course. Settlements, and the expansionist ideology they represent, have done great damage to the Zionist dream of a Jewish and democratic state; many Palestinians, and many Israelis, have died on the altar of settlement. The good news is that the people of Israel have fallen out of love with the settlers, who themselves now know that they have no future. After all, when Ariel Sharon abandoned the settlement dream—as the former prime minister did when he forcibly removed some 8,000 settlers from the Gaza Strip during Israel’s unilateral pullout in July 2005—even the most myopic among the settlement movement’s leaders came to understand that the end is near.

The prediction proved almost entirely wrong. There were about 450,000 settlers in the occupied territories at the time. Today, there are roughly 700,000, new settlements continue to be approved, and the settler movement is more powerful than ever.

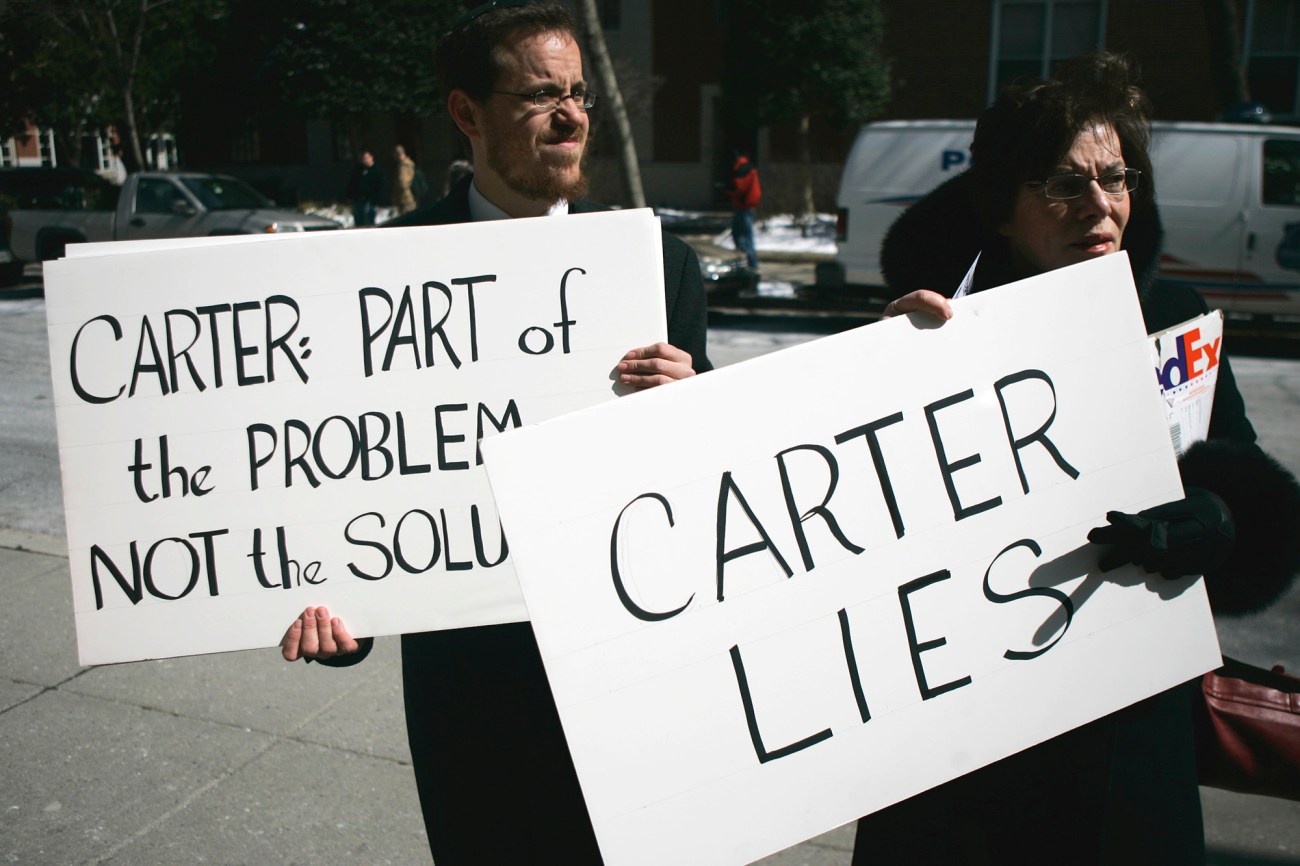

Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld of Ohev Shalom National Synagogue (left) and Carol Greenwald, chair of Israel Affairs Committee (right), protest Carter’s appearance at George Washington University in March 2007 to speak about Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid.

Charles Dharapak/AP

In the Post’s opinion pages, Deborah Lipstadt, who was Biden’s Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism, accused Carter of relying on “traditional antisemitic canards.” As evidence, she cited Carter saying that it was “political suicide” to have a “balanced position” on Israel and his having noted that “most of the condemnations of my book came from Jewish-American” groups. “Even if unconscious, such stereotyping from a man of his stature is noteworthy,” she added. “When David Duke spouts it, I yawn. When Jimmy Carter does, I shudder.”

The New York Times pushed back against the insinuations that Carter was an antisemite but was otherwise dismissive of what a reviewer called Carter’s “strange little book.” Nor was the condemnation limited to major newspapers. A review in Slate was headlined: “It’s Not Apartheid: Jimmy Carter’s moronic new book about Israel.”

Henry Siegman, a German-born Jew who fled the Nazis as a child before becoming the executive director of the American Jewish Congress and emerging as one of Israel’s most insightful critics, provided one of the few positive responses. Siegman wrote for The Nation that Carter was not anti-Israeli, much less antisemitic. He was just equally sympathetic to the suffering of Palestinians. That got Carter into trouble with Westerners and Israelis for whom the “Palestinian ordeal is invisible and might as well be taking place on the far side of the moon for all they know or seem to care about it.”

Carter’s response to the uproar was captured in what may have been a first in film history: A feature-length documentary about a book tour from a major Hollywood director. In Man From Plains, the late Jonathan Demme, whose previous credits included The Silence of the Lambs, followed the unusually vigorous 82-year-old—the former Navy officer swimming laps in hotel pools serves as B-roll more than once—as he promoted his new book across the country.

The documentary begins with Carter showing Demme the land his family had farmed in Georgia for the better part of two centuries. He returns to how that rootedness shaped his view of Palestine later in the film. “I own land in South Georgia that my family has had since 1833. I can just imagine how it would feel and what my physical reaction would be if a foreign people came in with a chainsaw and cut down my ancient trees,” Carter said. “This is so completely at odds with what I’ve always envisioned as the wonderful new nation of Israel—based on peace and justice and equity and human rights and democracy—that it’s almost inconceivable.”

The Elders, a group composed of Carter and other eminent global leaders brought together by Nelson Mandela, stand at a checkpoint between Ramallah and Jerusalem in 2009.

Tara Todras-Whitehill/AP

It was clear from remarks like those and others that he approached the conflict free of the bigotry he was accused of. His highest priority was securing peace in what, as a devout Christian, he considered to be the Holy Land. With Palestine Peace Not Apartheid, he tried to prevent the tragedy he saw coming. “It is obvious that the Palestinians will be left with no territory in which to establish a viable state,” Carter wrote. “The Palestinians will have a future impossible for them or any responsible portion of the international community to accept, and Israel’s permanent status will be increasingly troubled and uncertain as deprived people fight oppression.”

In the next paragraph, Carter offered a now unsettling warning about what form that violent resistance might take. He explained that Palestinian and Lebanese militants knew the value of a captured Israeli soldier or civilian. As a result, absent an Israeli commitment to peace, militants would have an incentive to obtain hostages. Israel would then respond with overwhelming and disproportionate force. But it likely wouldn’t be enough to destroy the hostage takers, Carter warned. After the bombs stopped falling, they would emerge more popular than ever.