I watch the news for a living and come across moments of political dysfunction at a regular clip.

So, I was not shocked to learn that Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), who until last month was second in the presidential line of succession, shoved a congressman in a “clean shot to the kidneys.” Nor was I particularly outraged to learn that on the same day across the Capitol, Sen. Markwayne Mullin, the Oklahoma Republican, challenged a union leader to a brawl, only to later go on Fox News and claim more members of Congress should normalize physical fights in order to maintain “respect” for the institution.

The episodes this week, equal parts reprehensible and dumb, were not aberrations on the right, where viral shitposting has effectively replaced public service. As I started to eye-roll the latest fisticuffs out of my brain, I recalled a 2019 conversation my colleague Tim Murphy had with Yale historian Joanne Freeman, an expert on congressional violence during the antebellum era. After January 6, I had been wondering how we should separate the performance of violence from the real thing, and what is risked when weaponized incompetence replaces enforcement of the most basic rules. I called Freeman to learn more. The following interview is edited for length and clarity.

What was your initial reaction to the Kevin McCarthy and Markwayne Mullin incidents?

My initial thought, as a historian who’s spent a lot of time focused on physical violence in Congress in the 19th century, was that this sort of thing happens in the modern Congress every now and again but what happened yesterday, all in one day, felt to me like a really obvious indication of the fact that the Republican Party is not a party right now.

Because if there was a functional party there, they would impose some discipline. They would have some kind of shared purpose or cause that would be keeping people in line and cooperating.

Lashing out happens from time to time. Maybe not as publicly or as often as it’s happening right now. But still, some of what we’re seeing now is explicitly because there are no brakes on the Republican Party. There are people who are extreme and are pushing things in an extreme direction. And others aren’t really saying very much about what’s going on. In some cases, silence is compliance.

Let’s talk about lawmakers like Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.), people who frequently invoke violence and name-calling against their perceived opponents. What do they suggest about Congress in 2023?

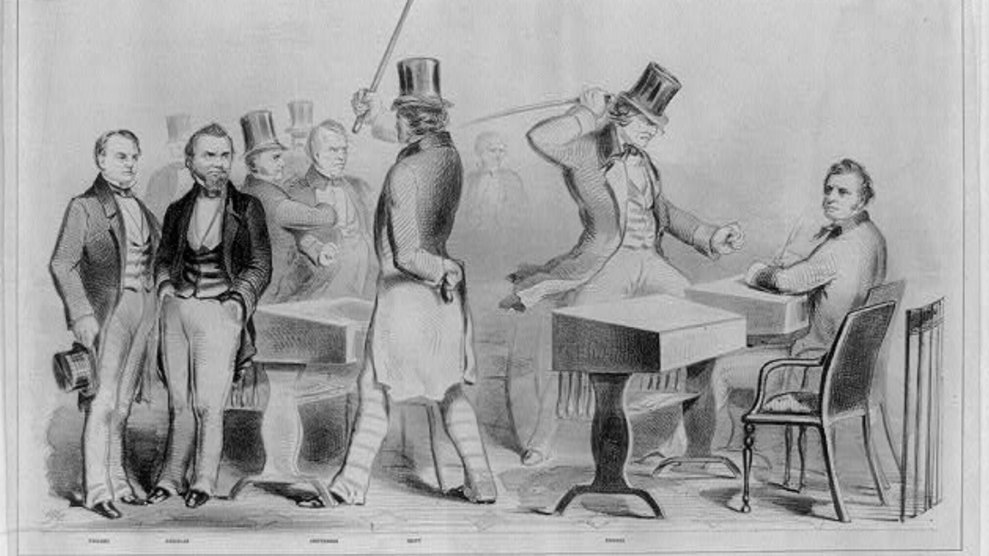

Looking back in time, the violence and the threats that happened in the 1830s, 40s, and 50s mostly came from Southerners who were willing to do or say anything to protect the institution of slavery. They didn’t necessarily care about the rules. What that meant was you had a group of people who were willing to engage in this violent bullying mode of politics. Not only were they not called to account for it but some of their constituents cheered them on for it.

On the other hand, you had mostly Northerners sometimes who did not like that kind of behavior—who very often after a bad incident, would [invoke] the rules. Now, strikingly, that’s what Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) did yesterday—when Mullin seemingly took his wedding ring off, stood up, and was ready to engage in a fistfight.

Right now, there’s not a lot of respect, particularly on the right, for the institution of Congress. Republicans don’t seem to be allowed to cooperate, to compromise, to do anything in league with the other side.

Mullin was later on Fox News where he invoked Andrew Jackson and the history of “caning” in the Senate to suggest that more members of Congress should normalize this behavior. What do you think of that?

There were so many aspects of yesterday that hit me over the head as a historian and that was one of them. In the days of dueling, the argument among those who approved of it echoed what Mullin asserted: That if people are afraid they are going to get shot for what they say, then they’re going to be careful of what they say. Once you had the Civil War, and the Southerners came back to Congress, many of them assumed that they would march right back in and behave that way again. But Northerners, having won that war, you saw them stepping in and saying: We’re a different kind of country now. We don’t operate that way anymore. That’s not acceptable.

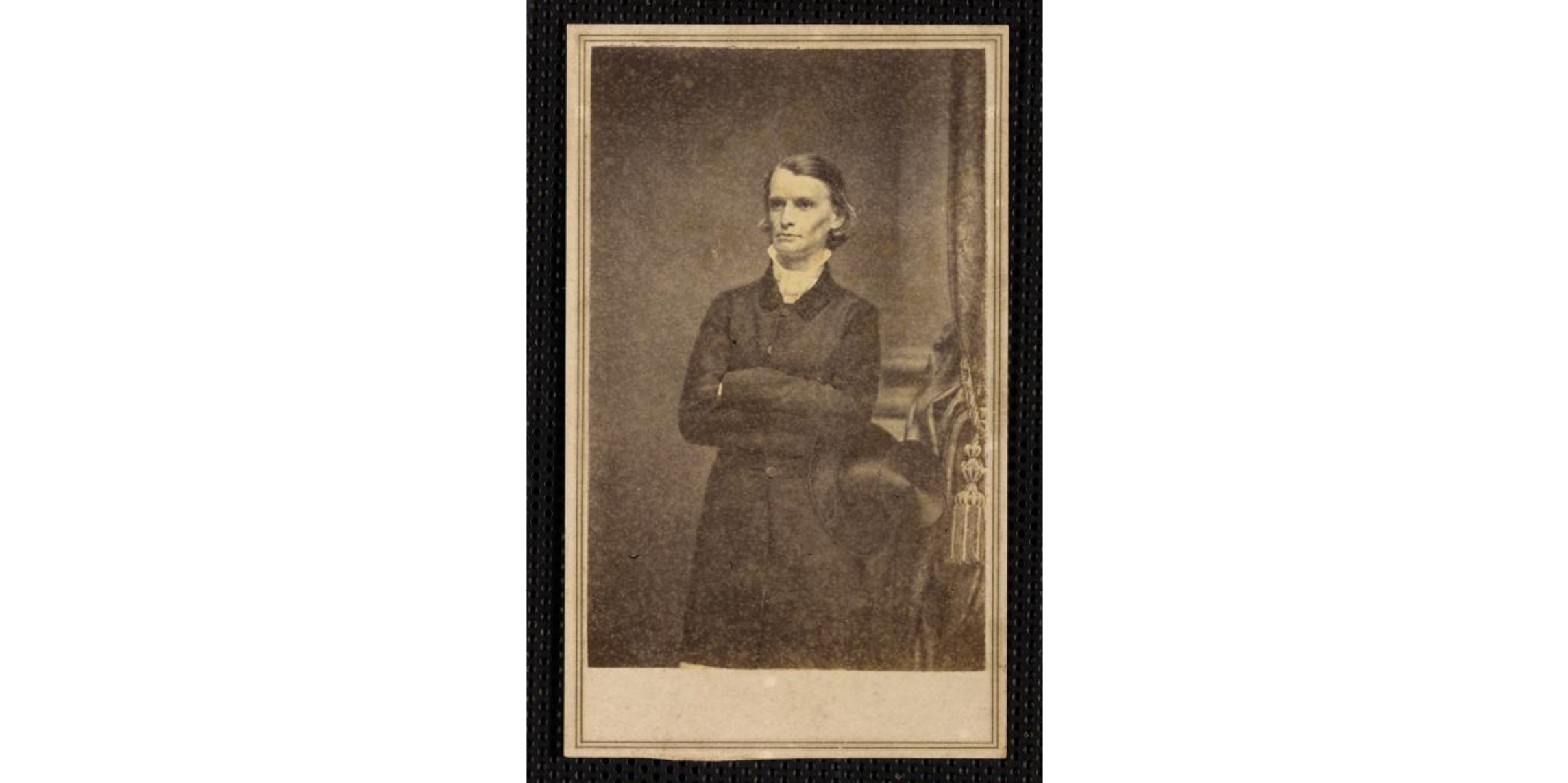

Another interesting thing that Sen. Mullin said is that his constituents want him to behave this way. There was a member of Congress named Henry Wise, a great opponent of John Quincy Adams and a supporter of slavery from Virginia. Wise got involved in more fights than anyone else and [Mullins’ argument] was essentially his argument too. In the same way that Mullin supposedly removed his wedding ring, Henry Wise would roll up his sleeves and get ready to fight at any given moment.

Henry Wise

Library of Congress

At some point, someone said to him: You should be ashamed of yourself. Your constituents should just boot you out. His response, and I’m paraphrasing, was something like: Go ahead, throw me out because you know what my constituents put me here to do that. They put me here to fight in whatever way I need to fight for their rights.

Henry Wise was reelected six times. So he was right; there was an audience and support from Southerners for that kind of behavior.

In any other working environment, you would be fired for this type of behavior. It’s crazy to me that Congress lacks similar rules.

Well, they have the rules. They’re just not enforced.

Exactly.

There’s such a long history of people in government behaving in corrupt and inappropriate ways and having absolutely no accountability for that. What’s happening now is in part because of social media. We see these moments that spread very quickly. There was a similar moment in the late 1840s and early 1850s with the telegraph, when suddenly the entire nation could learn something that happened in Congress within 45 minutes without congressional spin. Suddenly, members of Congress realized that whatever they did, it was going to go out into the world and that they couldn’t control it.

The telegraph meant that whatever happened in Congress became national property very quickly, and that scrambled democratic politics very quickly. We are very much living in a similar moment. Democratic politics relies on communication between the people and those in government, so any form of technology that scrambles that kind of conversation scrambles democracy.

One thing that struck me reading your conversation with my colleague Tim Murphy from a few years ago is the idea that, for the most part, people in government making these types of threats don’t truly want to inflict real harm. Has your opinion on that changed since January 6?

I still believe that most of the goals around this type of behavior, both today and in the period I write about, are not to be violent. It’s to frighten people off. To silence them and force them into compliance. As long as the threat is credible, you don’t necessarily have to be violent to have an impact. We are living in such a moment of crisis of accountability, in which no one wants to be held accountable for anything. You have election denial. You have people who feel free to be able to say anything. One of the core components of a democracy is that people with power are held accountable for the ways they use that power. That’s why free and fair elections and voting rights are core elements of a functioning democracy, and we’re watching them get eroded.

How do we separate the performance of violence from actual physical violence?

It’s hard to do. Some of this is and always has been performative, even in the period that I have written about. Back then, they did what they did, and then behind the scenes, they would try and talk things out. The problem right now is you don’t get the sense that there’s a lot of behind-the-scenes going on.

Henry Wise at one point threatened John Quincy Adams during a debate by telling him, “If you weren’t who you are, you would feel more than the force of my words.” (Adams in his diary later wrote, “So Wise, just threatened to kill me!”) But apparently, not long after Wise’s threat, he personally walked over to Adams and asked if they could talk it out. So clearly, some of that was obviously performance to both members of Congress and performance to the public. But right now, I’m not sure that the line is so obvious.

All of this—especially with anti-abortion extremists in government and a new speaker who believes in covenant marriage—feels plagued by masculinity and machismo.

It’s all about manhood and power. The brute force, chest-beating, and threat-tossing. That’s part of what we’re seeing.

The other part of what we’re seeing is that we are in a moment when the people who have power want to keep power and do not respect the rights of people who are not like them. When other people gain power—whether it’s demographically or democratically—they see it as an attack. It doesn’t represent more people having rights. It represents them losing what they feel that they deserve. They feel so absolutely entitled to power and they behave in a way that is manly, that allows them to pose as strong.

But it’s fundamentally a posture of fear and weakness.