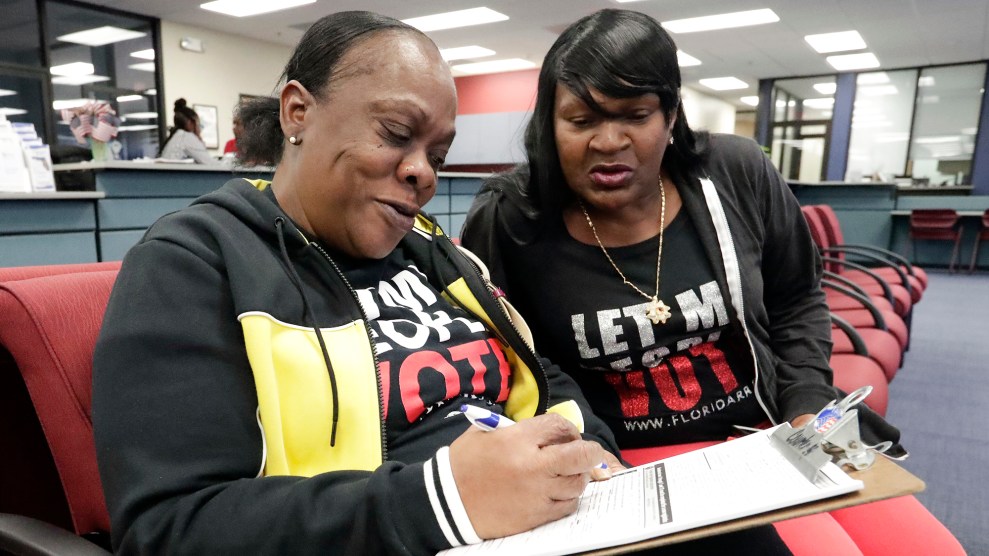

Desmond Meade, president of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, fills out a voter registration form as his wife Sheena looks on.John Raoux/AP

The Supreme Court struck a major blow against voting rights in Florida last week when it let stand a lower court decision that blocked as many as 1.4 million people who had previously been convicted of felonies from casting ballots until they pay all fines, court fees, and restitution. While the decision leaves intact a major financial barrier to voting, activists in the state are now banking on public support to help people pay down their legal debts and return to civic life.

The Supreme Court’s decision centers around Florida’s longstanding felon-disenfranchisement policy, which—as my colleague Ari Berman reported in 2018—has an ugly, racist history and can apply to people convicted of relatively minor crimes:

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, Florida disenfranchises more citizens than Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee combined. Ten percent of the state’s adult population is ineligible to vote because of a criminal record, including 1 in 5 African Americans. Florida counts 533 different infractions as felonies, including crimes like disturbing a lobster trap and trespassing on a construction site. “Come on Vacation, Leave on Probation” is an unofficial slogan…

After the Civil War, the white Confederates who still controlled Florida had a problem: The state had been forced to accept the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, which guaranteed equal rights for newly freed slaves, in order to rejoin the Union, and now black registered voters outnumbered white ones. White Floridians responded by adopting a constitution in 1868 that disenfranchised anyone with a felony conviction and added to the felony roster a variety of crimes they believed African Americans were likelier to be convicted of. One Republican leader said the law would keep the state from becoming “niggerized.” A decade later, more than 95 percent of people in Florida’s convict camps were African Americans.

In the same period, at least 12 other states—a third of the Union—adopted similar felon disenfranchisement laws. Before the advent of poll taxes and literacy tests, “felon voting restrictions were the first widespread set of legal disenfranchisement measures that would be imposed on African-Americans,” wrote Jeff Manza, Christopher Uggen, and Angela Behrens in the American Journal of Sociology.

In 2018, Florida voters overwhelmingly passed Amendment 4, a ballot initiative intended to restore voting rights to most ex-felons who have completed their sentences. But last year, the swing state’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, signed a law requiring ex-felons to pay all fines and court fees, which can range from hundreds to thousands of dollars, before becoming eligible to vote—a rule voting rights activists have likened to a modern-day poll tax.

This means 1000s of Floridians who paid their debt to society may not be able to vote in Nov. 64% Floridians passed ballot initiative restoring voting rights to ppl with past felony convictions but FL GOP enacted modern day poll tax requiring all fines, fees & restitution to vote https://t.co/oAlQoVkKI5

— Ari Berman (@AriBerman) July 16, 2020

Earlier this year, a federal judge blocked the restrictive new law, but the US Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit stayed that order, once again leaving people convicted of felonies unable to vote if they are unable to pay off their debts. Last week, the Supreme Court refused to reverse that stay, meaning that the law could remain in effect at least until after the November election. The case now returns to the 11th Circuit, which will hold a hearing on August 18—the day of Florida’s primary election.

“There were people who went to bed at night a couple months ago thinking that they were going to vote in the upcoming primary, and now they’re not,” says Neil Volz, deputy director of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, which works to reenfranchise voters. “Our initial reaction was sadness, which turned to anger, and now determination. Where other people see obstacles, we see opportunities.”

After the Supreme Court’s decision, Volz says, FRRC saw a huge influx of donations to its fines and fees campaign, which helps people convicted of felonies pay off their legal debts so that they can once again participate in the democratic process. As of July 20, that campaign has raised more than $1.3 million. That’s just a small fraction of the hundreds of millions of dollars that WLRN, the state’s public radio station, estimates people convicted of felonies owe across the state. Still, FRRC says that it has enabled hundreds of Floridians to vote by paying their fines and fees.

(FRRC is a project of the nonprofit Tides Advocacy. Mother Jones has received contributions from donor advised funds administered through the Tides Foundation. Both the Tides Foundation and Tides Advocacy are affiliated with the Tides Network.)

FRRC also teams up pro bono lawyers with ex-felons to find out exactly how much money they owe—a major hurdle given the lack of a streamlined system for accessing that information in Florida.

“No person in Florida should be precluded from voting because of money,” Volz says. “This isn’t a political science exercise for us. This is about our lives.”