Roy Moore and Doug JonesMother Jones illustration; Brynn Anderson/AP

If scientists could concoct the perfect experiment to test the outer limits of partisan polarization in today’s political climate, they might devise something like Tuesday’s special Senate election in Alabama. In a deeply conservative state, the experiment goes, if voters were forced to choose between a strong Democratic candidate and a wildly extreme Republican one accused of child molestation and repudiated by many party leaders, how far would they go to stick with their party? We’re about to find out.

The shortcomings of Roy Moore, the GOP candidate to fill the seat vacated by Attorney General Jeff Sessions, are well documented. He has said homosexuality should be illegal and that 9/11 was divine punishment for sodomy and abortion. He has called Islam a “false religion” and said Muslims should not be allowed to serve in Congress. And at a September campaign rally where he referred to American Indians and Asian Americans as “reds” and “yellows,” he said America has not been “great” since the end of slavery. Between stints on the state Supreme Court, from which he was twice removed for failure to follow the law, he earned more than $1 million from a religious nonprofit that failed to report all of his income to the IRS. Last month, multiple women came forward with credible allegations that Moore had sexually assaulted and preyed on them when they were teenagers, causing several prominent Republicans, including Alabama’s senior senator, Richard Shelby, to denounce his candidacy.

Doug Jones, Moore’s Democratic opponent, seems ready-made for such a political experiment. He is a former federal prosecutor who convicted two members of the Ku Klux Klan for murdering four young black girls in the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing in 1963, a line in his résumé that appeals to the black voters who make up the core Democratic base in Alabama. The son of a steel worker, Jones has the blue-collar bona fides to connect with the populist strain in Alabama politics. And he holds a sizable fundraising advantage, having raised more than $10 million by December 1, while Moore had not cracked $2 million.

And yet polls continue to show a neck-and-neck race, with Moore holding a slight lead in most surveys conducted this month.

“It used to be that certainly states and districts had their partisan bent, but in the right political climate, when the perfect storm developed, that seats could flip,” says Zac McCrary, a Democratic pollster in Montgomery. Alabama, he says, is currently a “laboratory” for whether that is still the case.

No election is a perfect experiment, and Jones’ campaign has not been glitch-free. Jones’ outreach to black voters focused too much on the past, say black Democratic leaders in the state, rather than what he would do for them. Meanwhile, his campaign cut ad after ad trying to win over conservative white voters on the fence about Moore, which some African Americans interpreted as a signal that Jones was taking their votes for granted. But in the past two weeks, the campaign has made a renewed effort to speak to the black community, airing a TV ad about education and ads on black radio stations about health care, two issues of particular importance to African Americans.

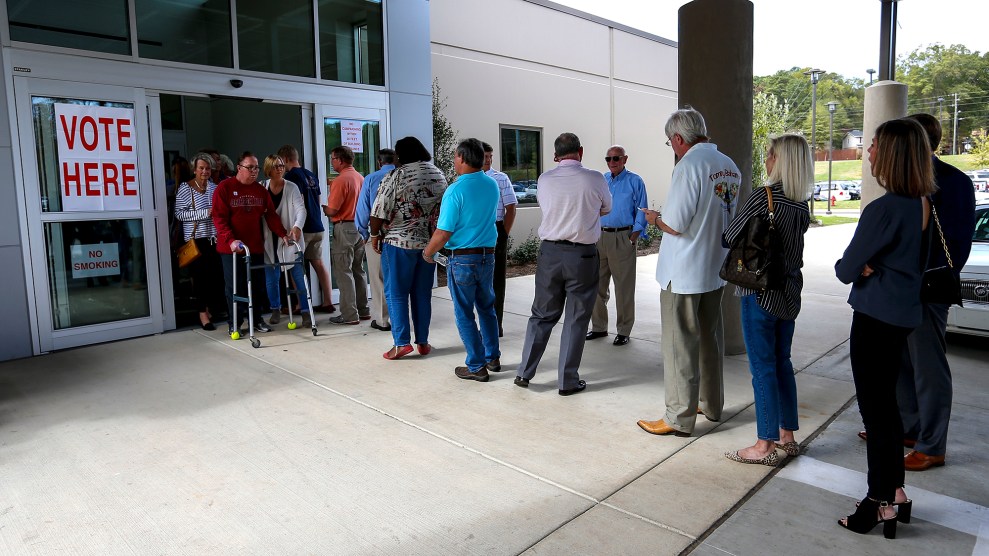

It’s unclear whether Jones’ ground game, or that of his allies in the state, is sufficient to mobilize enough black voters for him to win in a special election, giving the typically low turnout in these contests. Jones’ supporters are also likelier to be kept from the polls by voter ID requirements and other restrictions on voting in Alabama—an unavoidable variable in this experiment.

The biggest factor in Jones’ favor, beyond Moore’s historically compromised candidacy, is the fact that Democrats appear energized. This energy has carried them to victory in local races across the country this year, most recently in Virginia, where Democrats won the governor’s mansion and nearly took control of the highly gerrymandered House of Delegates last month. “Just the fact that this race is competitive does speak to a good election climate for Democrats,” says McCrary. Jones could “only pull this off because Democratic energy is high—Republican energy is middling to low.”

Polling has been erratic. The day before the election, two polls showed opposite results: One had Jones up 10 percentage points; the other had Moore up nine. It’s possible, as FiveThirtyEight‘s Harry Enten proposes, that Moore voters are shy about admitting who they are going to vote for, skewing polls with live interviewers toward Jones.

If the Alabama Senate race feels like a test of Republican voters, it’s not the first of its kind. In many ways, it is a follow-up study to the 2016 presidential election, where a fringe candidate won a plurality of primary voters over establishment opponents, then went on to win the general election despite shady business practices, racially charged messaging, an anti-Muslim platform, and accusations of sexual assault from more than a dozen women. Moore is in many ways the logical extension of Trump’s victory just over a year ago. If Alabama could embrace Trump—where he remains more popular than in most states—why couldn’t it embrace Moore, too?

Last year, Republicans who had initially resisted Trump faced a choice: support him, or let the party lose the election. Most fell in line behind Trump and told voters to do the same. House Speaker Paul Ryan appealed to conservatives’ desire to pass welfare and tax reform. With GOP policy priorities still hanging in the balance, top Republicans have largely dropped their opposition to Moore, or at least stopped talking about it. The president, who initially backed Moore’s primary opponent, endorsed Moore last week, encouraged voters to support him at a rally across the border in Florida, used his Twitter account to denounce Jones, and recorded robo-calls to get out the vote. The Republican National Committee followed his lead and announced its support for Moore just hours after the president did.

That Alabama could elect a Democrat to replace Jeff Sessions is remarkable in this political climate. But electing Moore, after this perfect confluence of events for Democrats, would send an equally strong message—that the Democratic Party can pretty much write off Senate races in the Deep South for the foreseeable future.