Olivier Douliery/DPA/ZUMA

Controversy continues to boil over President Trump’s executive order imposing an immigration ban and his policies aimed at aggressively deporting undocumented immigrants. Two other executive orders signed by Trump earlier this month, focused on fighting crime, have gotten less attention—but sections of them also appear to target America’s immigrant population, a former Justice Department official says.

Trump’s executive order concerning crime reduction and public safety instructs the Department of Justice to establish a new task force to crack down on illegal immigration, drug trafficking, and violent crime. Among its duties will be to “identify deficiencies” in existing laws, make legislative recommendations, and improve data collection on crime trends. Another Trump order, focused on combating international cartels that conduct human trafficking and drug smuggling, directs the DOJ to develop a strategy against these groups that “have spread throughout the nation” and “have been known to commit brutal murders [and] rapes,” driving “crime, corruption, violence, and misery.”

Thomas Abt, a criminologist at the Harvard Kennedy School and the former chief of staff for the DOJ’s Office of Justice Programs, says these executive orders involve the usual activities of the DOJ, but also imply strategic priorities that are misguided and troubling. “Here in the United States, I think a connection between immigration—legal or illegal—and violent crime is not one that there’s any evidence for,” says Abt. One order suggests that increased drug trafficking by cartels is responsible for a “resurgence in deadly drug abuse and a corresponding rise in violent crime,” but there’s little evidence to support that, says Abt. He notes that the current opioid and heroine crisis took hold well before the recent spike in violent crime in some US cities.

There is also no evidence to suggest that cartels are more active in the US now than they have been historically. And while mayhem from the drug cartels ravages Mexico and central American countries, and is played up by anti-immigration pundits, violence in the US connected to the cartels is nowhere near that scale. Research published in 2015, for example, found that even at the height of cartel violence in 2010, there was “no notable increase” in crime along the US side of the border that correlated with the spike in murders in Mexico.

“The way it’s being framed as this new Bogeyman is just not accurate,” Abt says. Moreover, the executive orders “suggest that what’s coming next is not a smart, data-driven approach to these issues. They suggest the beginning of a fear-based effort.”

Abt sees a potential return to 1980s and 1990s tough-on-crime policies—championed by Attorney General Jeff Sessions—that have been eschewed as ineffective by leading crime reduction experts. With the call to “assess” the allocation of money and resources to federal agencies’ for fighting international criminal orgs, Abt also says there could be a shifting of resources by the Trump administration from proven crime-reduction efforts to ideologically based efforts.

Perhaps most troubling, Abt says, is a Trump directive to publish a quarterly report on the criminal convictions of people involved with international criminal organizations. This could be used as a pretext to discriminate against immigrants—similar to how the threat of terrorism is being used to justify banning travel by immigrants from the seven Muslim-majority countries.

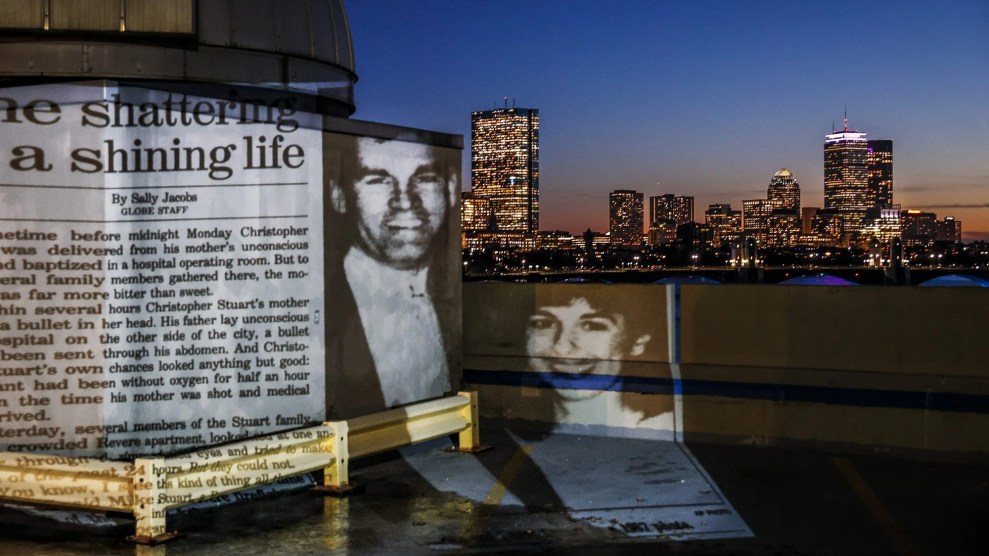

“It’s clearly designed to marshal public opinion,” Abt says. “This is Willy-Horton-style, everybody-get-scared type of politics.”