In the not-so-distant future, if current trends continue, more Americans will die from gun violence than from auto accidents, but the state of Utah is wrestling with the fact that it hit that grisly benchmark a few years ago. And it’s not “bad guys with guns” driving this trend; the vast majority of gun deaths in Utah for the past few years (89 percent in 2011; see chart) were people taking their own lives.

Among them was 14-year-old David Phan, who walked onto the skybridge in front of his junior high school this past November and, in front of his schoolmates, put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. His death was one of more than an estimated 500 suicides in Utah in 2012, more than half of which likely involved a firearm. (Utah is one of only five states where gun suicides alone exceed traffic fatalities: Check out our state-by-state map.)

Driving fatalities, another leading cause of preventable death in Utah, hit a historic low in 2011 following a long, downward trend. But gun suicides have been rising. Utah is a pretty heavily armed state—nearly half of its residents own guns. At the same time, it is often referred to as the “most depressed state.” Utah residents consume antidepressants at twice the national rate and its rate of suicide—the state’s second-leading cause of death for ages 10 to 19—consistently beats the national average. Utah also leads the nation in the proportion of adults reporting suicidal thoughts.

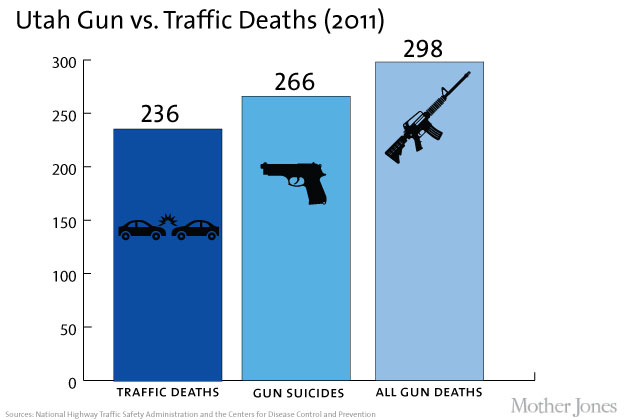

Thanks to the easy availability of guns, more and more Utah residents have acted on those dark thoughts. The rate of gun suicides per 100,000 residents has jumped from an age-adjusted 7.8 in 1999 to 10.6 in 2010. And here’s a breakdown of the total numbers for 2011, the most recent year for which data is available:

And this is in spite of the fact that far more residents drive, and drive a lot, than own guns. Based on preliminary numbers, the 2012 gun suicide figure is expected to be higher still, according to Jenny Johnson, a spokeswoman for the Utah Department of Health.

The uptick in suicides has caught the attention of state legislators, who seem to have been particularly horrified by Phan’s death. But virtually all of their emphasis is on combating bullying, not on making it harder to kill yourself. The Legislature is on the verge of passing several laudable bills designed to increase communication between parents and school counselors, requiring school staff to notify parents if a student makes a suicide threat, for instance. But gun safety measures aren’t really on the table, even though nearly half of the young people who take their lives in Utah do it the way Phan did it.

Firearms are a “really politically sensitive topic for our state,” explains Johnson, the health department spokeswoman, who acknowledges the reality of the role of guns in suicide. “It is a risk factor if you have access to a gun and you have some of these other risk factors. We do tell people removing those lethal means is one way you may be able to prevent it. Especially for men and teens, where teens are very impulsive, the more lethal means they use, the less likely they are to survive.”

There are some things legislators could do, even in a state where every other person is armed, such as mandating gun locks and secure storage for guns in the home. Research shows that suicide is an impulsive act—one study found that 25 percent of people who attempted it did so after deliberating for less than five minutes—and most had considered it for less than a day. Usually the impulse strikes not long after an interpersonal crisis of some sort. (Phan shot himself an hour and a half after being suspended from school and taken home by his mother.)

And lots of research shows that most people who attempt suicide and survive don’t ever try it again. That’s why suicide prevention efforts are often geared at making lethal means less accessible with things like gun locks and safes—to which kids should not be given the code. “Every minute you can delay, [a suicidal person] increases the chance that they might survive,” David Litts, executive secretary of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, told the Boston Globe recently.

Rather than pursuing these sensible steps, Utah is plowing ahead with measures that make guns even easier to get and carry. The Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence has described Utah’s “crazy” gun laws as the nation’s weakest. Among other things, last year Utah passed a law to allow people who’ve been indicted for a violent felony to buy a gun. Being charged with a violent crime is no longer grounds for suspending a concealed weapons permit in Utah.

The state Legislature apparently believes there’s still more to do: Last month, an 18-year-old made headlines when he came to the Capitol building sporting a 9 mm handgun on his hip. He had come to attend a hearing in support of a measure that would allow him to put a coat over his gun—in Utah, you can legally walk around openly armed in public, but you need a permit if you want to conceal your weapon. Last Friday, the Utah House passed a bill that would let residents pack concealed weapons without a permit, which would put it on the list of “constitutional carry” states like Vermont, Alaska, Wyoming, and Arizona—some of which rival Utah in terms of suicide rates.

Getting a concealed weapons permit in Utah now requires a background check, which last year weeded out more than 600 people, including many with convictions related to domestic violence, drugs, and alcohol. If the constitutional carry bill becomes law, that extra check on gun owners will disappear—more suicides could result, research suggests.

To its credit, Utah has done one thing right this year. Among the many gun bills the Legislature is considering, one that actually seems likely to pass includes a smart provision advocated by the Harvard Injury Control Research Center: HB 121 would let people hand over their guns to the police for 60 days if they suspect that they, or someone in their household, might be a danger to themselves or someone else.

Rep. Dixon Pitcher, the Republican who introduced the bill, told a Utah public radio station that he thought it would save lives. “This takes no rights,” he said. “I’m a strong believer in the Second Amendment, but it gives to the person who needs this the availability to have that gun away from the house for a short period of time.” Pitcher has the right idea, but whether his bill will be any match for the wave of new pro-gun laws the state seems bent on passing is anyone’s guess.

Note: All suicidal thoughts, behaviors, and attempts should be taken seriously. Get help 24/7 by calling the National Suicide Prevention LifeLine at 1-800-273-TALK. Help is also available online at www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org. Trained consultants will provide free and confidential crisis counseling to anyone in need.

Chart art sources: James Bond Icons and Richard Pasqua from the Noun Project