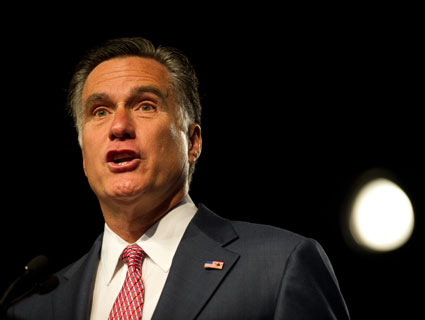

Mitt Romney offering remarks before a curling event at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Utah.<a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mitt_Romney_SLOC.jpg">Uncleweed</a>/Wikimedia commons

As Mitt Romney got ready to take his seat in London for the Olympics’ opening ceremonies, the focus of the presidential campaign this week shifted to the candidate’s time running the 2002 Winter Games in Salt Lake City. Romney is generally recognized as the take-charge executive who turned the Games around after a massive bribery scandal. But there’s another side to that record. Romney’s campaigns, as we’ve previously reported, have taken in $1.5 million in donations from the families and business associates of two central figures in the Salt Lake scandal. And documents obtained by Mother Jones shed new light on another of the candidate’s Olympic connections—his personal intervention on behalf of his closest Salt Lake friend, developer Kem Gardner, in connection with a key real estate deal.

At issue is the Olympic Legacy Plaza, a public square in the Gateway, a massive shopping/retail/office complex that Gardner was developing at the time. The plaza features the 2002 Games’ snowflake logo, a fountain, and a concrete “wall of honor” listing donors and volunteers. No other bids or sites were considered for the project, which helped Gardner secure a multimillion-dollar city tax break for building a public plaza. Romney also wrote a memo discouraging other municipalities from building competing projects, and he helped fill a Gateway housing complex with media representatives during the Games. Gardner, his family, and his business associates have since given more than $500,000 to Romney’s campaigns.

“I couldn’t love him more,” Romney once said of Gardner, whom he’s known since the two of them were prominent Church of Latter-day Saints officials in Boston—they ran the local Mormon stake, roughly the equivalent of a Catholic diocese—in the 1980s. It was Gardner, a longtime Olympic booster and chair of the 2002 Games’ fundraising subcommitee, who got Romney the Salt Lake job. Over the years Gardner has also house-hunted with Romney in Utah, provided a city apartment for him to use on nights when he worked late on the Olympics, headed the Olympics Ambassadors fundraising organization at Romney’s behest, and traveled with Romney and five others to the games’ official torch lighting ceremonies in Athens in 2002. Gardner even employed Romney’s son Josh until recently. “We talk every other day and exchange emails,” he told the Idaho Statesman last year.

While the Boston Globe explored the Romney/Gardner relationship during Romney’s 2002 gubernatorial campaign, Mother Jones has obtained documents that reveal just how far Romney went to secure the Olympic legacy park designation for Gardner. They include a January 12, 2000 letter from Gardner to Romney claiming that the Salt Lake City Organizing Committee (SLOC) had “initiated ongoing discussions with us concerning your interest” in a legacy plaza at Gateway, and contending that Gardner’s proposal was “in response to these requests.” But the next day, when Romney recommended approval of the project at an SLOC meeting, he didn’t mention soliciting the proposal; instead he characterized it as “an offer that SLOC had received.”

Gardner’s letter said the “only quid pro quo” the company expected was the plaza’s “perceived benefit to the Gateway and our desire to be supportive citizens.” The plaza brought 70,000 to 100,000 visitors a day to the mall during the Games, and to this day the complex advertises itself as “a destination for many visiting Salt Lake City” because of its Olympic connection. Romney returned to the plaza for an Olympic anniversary ceremony in 2003, and again this past February.

Two former Olympic trustees told Mother Jones that the plaza was never discussed at board meetings before Romney proposed it. “All of a sudden, it just appeared,” said one, who asked that his name not be used. Ken Bullock, a prominent trustee, told the Salt Lake Tribune at the time that Romney had “overstepped his bounds” by going “around making unilateral commitments.” The Olympic Legacy Plaza inside Kem Gardner’s massive Salt Lake City Gateway complex. Amy the Nurse/Flickr

The Olympic Legacy Plaza inside Kem Gardner’s massive Salt Lake City Gateway complex. Amy the Nurse/Flickr

The resolution Romney submitted to the SLOC board said the organization would “pursue other opportunities to develop similar legacy projects.” But two months later, Romney wrote an internal memo saying that while other cities had asked about building Olympic legacy parks, “we do not want” similar projects. Gardner was soliciting $50 contributions to the Olympic committee for engraved bricks to be installed on Gateway walkways, and Romney noted that fundraising for other parks might hurt that push. When critics pointed out that only donors—not athletes—were honored at Gardner’s plaza, Romney promised to get another project underway, but that never happened.

But perhaps the most perplexing part of the Gateway deal is that nothing in the SLOC minutes indicates that Romney disclosed his relationship with Gardner—even though, just six months earlier, he had pushed through a new set of ethics rules for the scandal-plagued organization, specifically requiring “key employees” to disclose any “relationship with any outside organization or person that might affect (or that might reasonably be understood or misunderstood by others as affecting) the objectivity or independence of his or her judgment or conduct.” Those rules also called for 48 hours’ notice before any board resolution; Romney’s proposal was submitted just one day before the meeting.

Beyond his friendship with Romney, Gardner also had connections to some of the more controversial figures in the Salt Lake Games. He’d been close to Tom Welch, the Olympic CEO who was indicted in 2000 for orchestrating the Salt Lake committee’s alleged payoffs to the International Olympic Committee (Welch was acquitted of those charges in 2001.) While Gardner was never implicated in the favors, he was on the board of Intermountain Health Care, a hospital system that provided free medical care to three IOC members at the request of the bid committee led by Welch. The hospital chain covered everything from cosmetic surgery to a knee replacement for a total of at least $28,000. The board member designated to interface with the Olympics was Gardner.

Later, when the feds were investigating Welch, Gardner insisted on setting up a conference call between himself, Welch, and Romney. Welch later claimed that Romney promised him that if he pled guilty, “he would look into a way of getting me” the $1 million Welch claimed the Olympic Committee owed him. Romney acknowledged at the time that he was trying to convince Welch to take a plea, but said he was only offering to pay his legal fees. Romney has said that the call “was a very bad idea and I don’t intend to ever do it again,” but he did wind up approving millions in legal fees for Welch and others before leaving Salt Lake in 2002. Gardner remained so close to Welch that he gave his family tickets to the Games and called him a “martyr.”

Gardner remained similarly loyal to Romney over the years. In 2006, the Boston Globe reported that Gardner, Josh Romney, and Romney aide Don Stirling had negotiated with top Latter-day Saints leaders “to map out a national network of Mormon supporters” for Romney. Gardner, who’d arranged the meetings, took responsibility for “this whole mess” in the media.

The following year, Gardner chartered a JetBlue plane to fly 150 people to Boston to help raise funds for Romney’s first presidential bid. The staff of the Federal Election Commission investigated, finding that the excursion was a violation of campaign donation limits (one participant later boasted that the group had raised $700,000), but the commission ultimately deadlocked on the findings and no sanctions were issued. Even as that controversy was brewing, Romney named Gardner a co-chair of his national campaign finance committee.

Though Gardner has a long history of talking with the press—he first tipped off the FEC by bragging about the JetBlue trip to the Salt Lake Tribune—he did not respond to our inquiries. But along with other controversies around the 2002 Games, the Gateway episode continues to raise questions about Romney’s Olympic record.