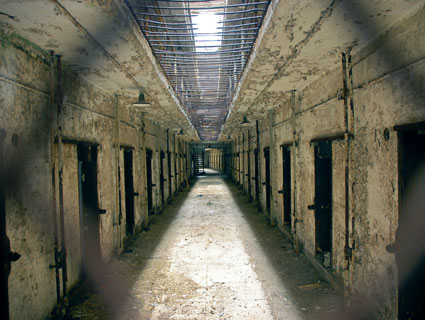

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/46473296@N02/6680392721/">Justin Norman</a>/Flickr

Facing a serious civil liberties backlash, Congress is considering changing a controversial counterterrorism law it passed last year. Yet the leading fix, backed by House Republicans, may not be a fix at all.

Last year, during consideration of the National Defense Authorization Act, Congress came close to authorizing the indefinite detention of American citizens captured on US soil who were suspected of terrorism. Ultimately, the House, the Senate, and the White House agreed on a compromise that would let federal courts decide whether such detentions were constitutional. That is, when confronted with the knotty question of whether the US government can detain its own citizens within the nation’s borders without charging them with a crime, Congress decided not to decide. Still, activists on the left and right remain concerned, because although President Barack Obama promised not to use that power, the law does not explicitly prevent him from doing so. In the months since Obama signed the bill in January, a strange-bedfellows alliance has raised such a ruckus over the legislation that Congress is now considering three separate proposals to amend the law.

“There has been significant constituent concern” over the NDAA, says Claude Chafin, a spokesman for Republicans on the House Armed Services Committee.

The revolt against the NDAA has brought together organizations and activists that disagree on almost every other issue—tea party activists, the states’ rights Tenth Amendment Center, the American Civil Liberties Union, and Occupy Wall Street protesters. The NDAA is “waking people up to the idea that the federal government shouldn’t have this kind of power,” says Michael Boldin, the director of the Tenth Amendment Center. “We’re seeing this weird mishmosh coalition of people.” In mid-April, Boldin’s group joined a number of other conservative organizations in filing a friend-of-the-court brief in support of liberal journalist Chris Hedges’ anti-NDAA lawsuit against the Obama administration.

The NDAA backlash has already fueled action on the state level. In Virginia, Republican Gov. Bob McDonnell recently signed a bill that could prohibit state authorities from “knowingly” aiding in the military detention of a US citizen. The Arizona Legislature passed a bill making it a misdemeanor for state officials to help the feds detain US citizens under the NDAA, and the Maine Legislature passed a joint resolution urging Congress and the president to amend the law to make it clear that Americans apprehended on US soil can’t be detained without trial. All three states have legislatures with Republican majorities.

Congress is now considering three bills designed to quiet the uproar. One, sponsored by Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas), would repeal the detention sections of the NDAA entirely. Another, sponsored by Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.), would ensure that suspected terrorists captured on US soil, whether they are citizens or not, could not be detained indefinitely without trial.

Then there’s a third bill, proposed by Rep. Scott Rigell (R-Va.), called the Right to Habeas Corpus Act. Rigell’s bill, which has 32 cosponsors, would do basically nothing. That’s because all it does is affirm the right of American citizens to have a judge evaluate the legality of their detention, and there has been no disagreement over that right since the Supreme Court affirmed it in 2004. The question has been whether the United States could hold suspected terrorists without ever charging them with a crime. Under Rigell’s bill, a future president could still potentially indefinitely detain an American citizen arrested in the United States on suspicion of terrorism, while Smith’s bill would prevent them from doing so.

Rigell’s bill is “addressing a habeas problem that doesn’t exist, and ignoring the real problem, which is indefinite detention without charge or trial,” says ACLU legislative counsel Chris Anders.

Rigell’s office didn’t respond to a request for comment. But Anders notes that detention authority can be a “confusing” and “difficult” area in which to legislate, partially because many of the issues aren’t entirely settled. Of the two bills that would actually alter the NDAA, Smith’s has 56 cosponsors in the House. Paul’s bill has five cosponsors.

Republicans in the House, however, seem much warmer to Rigell’s mostly symbolic legislation, with Chafin insisting it would “put to rest any doubt to the…purpose of last year’s NDAA.” The law’s critics don’t believe that. “We don’t trust Congress, who just passed this thing into law, to all of a sudden say, ‘Oh, we were wrong; we’re going to change it,'” Boldin said. That’s probably a safe bet.