Mississippi voters overwhelmingly rejected a ballot measure that would have granted full rights to a fertilized egg on Tuesday, with 58 percent of the state voting against the amendment. Activists on both sides of the battle were watching the state as a test case for other state-level initiatives that would outlaw all forms of abortion. Perhaps it’s worth looking, then, at why it didn’t pass in one of the most conservative states in the country.

The primary reason for the measure’s failure was overreach. In recent weeks, opponents of the measure made the case to the public that it wasn’t really just about abortion, but could also have far-reaching impacts on birth control, in vitro fertilization, and a doctor’s ability to provide care for pregnant women. Nsombi Lambright, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Mississippi, pointed to the many grassroots and medical groups that got involved in the debate that were outside of the traditional abortion rights supporters like the ACLU and Planned Parenthood. In the past weeks, those groups were also knocking on doors, appearing in public forums, and making phone calls.

The Mississippi Nurses Association and the Mississippi chapter of the American Congress of Obstetrician Gynecologists came out against the measure, as did the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. The Mississippi State Medical Association also declined to endorse it, with the group’s president expressing concern about the “unintended consequences” of the measure and that the “medical judgment of well-intentioned physicians could be brought into question” if it passed.

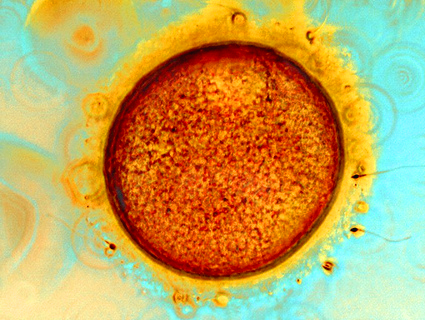

A group of doctors also came out against the measure in a press conference at the state capitol. Dr. Randall Hines, a Flowood, Mississippi-based OB/GYN who specializes in infertility treatments, tells Mother Jones that the testimonials on Facebook and other social media tools from women were another key factor in the measure’s defeat. “The number of people who themselves, a family member, or a close friend has experienced infertility…we’re talking about a big chunk of the population,” Hines says. “I think that was overwhelmingly what got this thing defeated.”

Hines also cited the involvement of grassroots parents groups like Parents Against MS 26, an effort started by Atlee Breland, a mother of three who dealt with infertility. “The way I built my family was under threat,” Breland said. “I couldn’t let that go.” She launched a website with the stories of women who had undergone fertility treatments, been through rapes, or suffered traumatic miscarriages. Many of the women described themselves as firmly pro-life, but concerned about the broader reach of measure.

The measure also split the anti-abortion community. The National Right to Life declined to endorse it, as did the bishop of the state diocese of the Catholic Church. For some anti-abortion activists, the problem with the measure was that it took a sledgehammer to Roe v. Wade at a time when most national anti-abortion groups have opted for a scalpel. Had it passed, it would have ended up in court inevitably. As a result, some people who may have voted for a measure limiting abortion rights ended up voting against Initiative 26. Other religious leaders, including the bishops of the Episcopalian and Methodist churches in the state, also came out against it.

Alexa Kolbi-Molina, a staff attorney at the ACLU’s Reproductive Freedom Project, notes that this is the fifth time that voters have rejected an all-out ban on abortion at the polls, which should be a sign to “personhood” advocates. Both Colorado and South Dakota have twice rejected similarly blunt measures. “When you ask people, they trust women, they want women to make decisions themselves, and they want the government to keep out,” she said. “If it wasn’t clear before, it should be now, that nobody supports this extremist agenda.”