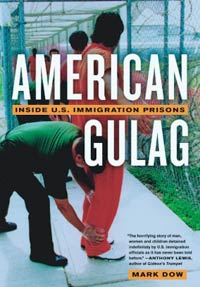

In the Los Angeles Times earlier this year, Mark Dow, a freelance journalist, wrote: “The first I heard about rituals of sexual humiliation in prison had nothing to do with Abu Ghraib.” For the past decade, Dow has been exposing and uncovering the prisoner abuse that takes place right here in the United States, inside the nation’s federal immigration prisons. In his new book, American Gulag: Inside U.S. Immigration Prisons, Dow describes the network of immigration detention centers and details the abuses that take place in them, and the efforts by government officials to conceal what is happening.

In the 1980s, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) began an aggressive policy of detaining certain political refugees and other undocumented aliens. Many of these prisoners are “criminal aliens,” immigrants who have already served prison terms and are waiting to be deported. Others are merely seeking asylum, such as the thousands of Haitian “boat people” who were detained en masse during the Reagan years. Overall, about 200,000 people are detained annually. Since September 11, immigration policy has become more stringent still, targeting Arab, Muslim, and South Asian foreign nationals.

The prisons themselves are often gruesome. Detainees — many of whom have committed no crime — are often subjected to beating, humiliation, sexual assault, isolation, and verbal abuse. The guards themselves are often unprepared for the environment. One officer, after being convicted for repeatedly kicking and punching an inmate, told Dow, “It was a situation I had never been in … I reacted … I don’t know what happened.”

Almost as disturbing is the veil of secrecy surrounding the detention centers. In his investigations, Dow was often prevented from interviewing prisoners, accessing medical records, and looking at immigration guidelines. Dow also found that INS — which has now been folded into Homeland Security — answers to no one. It often eschews formal regulations. There are no monitors or independent watchdogs around. Most of what we know about these prisons comes from a handful of journalists, working tirelessly to “make public what the INS tries to hide.”

Dow recently spoke by phone with MotherJones.com about some of the disturbing facts he’s uncovered about America’s immigration prisons. What follows is an edited transcript of that conversation.

MotherJones.com: Describe the typical process an immigrant will go through after being picked up by immigration.

Mark Dow: Unfortunately there’s not always a typical process. If you look at the flow chart included in the Office of the Inspector General’s report about immigration, it is not straightforward at all. This makes it incredibly difficult to track these detainees.

But as far as people I’ve written about, first you have immigrants who come into airports without proper documentation. If that person is allowed to pursue political asylum, then they go into detention. Of the 23,000 “administrative detainees” in detention, asylum seekers make up about 10 to 13 percent. We don’t know the exact number because the immigration service hasn’t provided any numbers, in spite of a statutory requirement that they do so.

Second, a person with, say, a visa overstay can be picked up by an immigration agent and taken to detention — either an immigration detention center or a contracted jail.

And then you have people with some kind of criminal conviction who are picked up. Since the late 1980s, the immigration service has been tracking non-citizens in the criminal justice system. So once an immigrant completes a prison sentence, he or she can be turned over to the immigration service. Let me add that a lot of people picked up in this way were never sentenced to jail time, because they had minor convictions, but these immigrants can still be subject to detention and deportation.

MJ.com: What happens then? Can those immigrants with criminal records be held indefinitely?

MD: Indefinitely is a loaded word. In a general sense any immigrant detainee is subject to indefinite detention, without a release date. The immigration service has the authority to detain someone in order to deport him or her. Now technically, this person is not being held as punishment. Technically. In practice things are very different. What happens if someone to be deported and no one will take that person? This is a situation we’ve seen with Cambodians, Vietnamese, Laotians, Libyans, Iraqis, Cubans…

There was an important Supreme Court case in 2001 — Zadvydas vs. Davis — where the court ruled that the immigration service cannot detain someone indefinitely simply because it is unable to deport that person. Well, it seems clear that the government is not complying with the Zadvydas decision. I say that partially because of reports I’ve seen from attorneys around the country. Likewise, a report from the GAO in May 2004 notes that there are problems in tracking whether the immigration service is actually in compliance. The agency also uses legal technicalities to exploit the law. I spoke to a Mariel Cuban prisoner who served about 2 years in California state prison and was then held for twenty years by the INS because the Cuban government would not take him back. Well, the INS was able to hold him by citing an “entry fiction,” saying that he had not legally entered the country, even though Mariel Cubans have been here for a quarter century.

MJ.com: So who’s making sure that these agencies comply with the law?

Well there’s the big question of what makes the immigration agency accountable. The GAO report seems to suggest that the agency itself make improvements to ensure compliance with the law. Likewise, a similar report from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), criticizing treatment of post-9/11 detainees in Brooklyn, suggested that the Bureau of Prisons police itself. Even though the same Bureau withheld evidence from the OIG about allegations against correctional officers. Obviously that’s not going to work. So we need some kind of oversight from outside Homeland Security. We need someone, some sort of ombudsman, who reviews every case in detention and makes sure people are detained lawfully and then monitors the treatment of all these people.

MJ.com: How much access do detainees usually get with the outside world, especially in terms of legal representation?

MD: Another improvement that can be made to the system is that all immigration detainees should be appointed legal counsel. The detainees are not entitled to government-appointed counsel, although they can have lawyers if they can get them. One of the problems, however, is that being a detainee makes it really hard to get a lawyer. Typically the prisoners can only make collect phone calls from jail, and a lawyer’s office will rarely accept collect calls from an unknown person. And remember that immigration officials can move detainees at will, typically in the middle of the night, from jail to jail around the country. They can be moved to rural areas without an immigration bar, without lawyers who will work on pro bono immigration cases. At one point the American Bar Association tried to enact a standard to prevent such transfers, and not surprisingly, the INS refused.

MJ.com: How widespread is the prisoner abuse in immigration prisons?

MD: I don’t have statistics, but I’ve talked to many prisoners and jailers, and visited a number of detention centers. In my experience, extreme forms of physical abuse are common, and not just aberrations. It seems to be something that grows naturally out of the ways in which prisons are run. That was made most clear to me in a conversation with a warden in Louisiana, who described what it’s like for a 20-something-year-old guard with minimal training to suddenly be in a dorm room with a bunch of angry prisoners who don’t want to be there. It sets up a certain atmosphere.

And both prisoners and correctional officers have emphasized to me that, although dramatic beatings or sexual humiliation are more likely to make the newspaper, there’s a daily degradation and dehumanization that’s part of prison and has nothing to do with any kind of sentence. That is often what makes life really unbearable.

MJ.com: What role do you think racism plays in the way the detainees are handled?

MD: I think automatically of two pre-9/11 stories. One of them involves a Palestinian who was beaten by INS officials in California and told that it was in retaliation for the Beirut bombing. Another is an allegation by India Sikhs who were taunted as terrorists. It’s also worth noting that Nigerians in are subjected to a lot of targeted abuse, because they tend to know what their rights are, and tend to speak English, which is a dangerous combination as far as immigration officers are concerned.

I don’t think the INS invents this stuff; it’s part of the culture of enforcement. When you have control over a person and part of the reason for that control is what that person is, in this case, an “alien”, then a lot of masks come off. But at times immigration policy has helped to spearhead those prejudices by making them official. One of the things I saw happening over and over again was that the prejudices that existed at the policy level in Washington get played out on the ground. Years ago at the Krome detention center in Florida, I heard about detention officers who were ridiculing Haitian women for coming to America because they only wanted more food. But these officers were basically mimicking the federal policy against Haitians, which said these people were not entitled to political asylum because they were only economic migrants.

MJ.com: What about detainees who call attention to their conditions, or try to contact the media? Are they singled out for retribution by prison officials?

MD: That is extremely common. This particular prison system is extremely repressive, and the system retaliates against prisoners who attempt to contact the media, or against those who go on nonviolent hunger strikes. That retaliation can include everything from beatings to transferring prisoners to isolated jails away from their families and attorneys.

This is an important example of the unchecked and arbitrary authority that the immigration agency has. In my book I describe a Palestinian who is transferred from jail to jail, and the immigration service is trying hard to keep him from contacting the media, which he’s very good at doing. Eventually the guy gets released, and as a condition of his release, INS told him he could not speak to the media about his case. If he did, they would lock him back up. The thing is, none of this has anything to do with immigration. Forbidding someone from talking about his or her case to the media has nothing to do with any argument about borders or national security. It’s simply the result of excessive authority and an obsession with secrecy.

MJ.com: Do you see any way to change this system, this culture?

MD: There have been calls for monitoring prisons and jails and detention centers. This is good, but I think it’s important to realize that that’s never going to happen from on high. Local communities and activists around the country need to go to their immigration offices and go to their local jails and begin discussions about setting up some sort of monitoring. Independent surprise monitoring is probably the only thing that will protect immigration officials and correctional officers from this sort of thing.

MJ.com: How, in your experience, do detainees cope with their situation, in your experience?

MD: You know, it varied widely. But it’s an interesting question because it helps me to remember that even though we’re talking about the repression of this immigration prison system, we’re really talking about people and human beings on both sides.

I think about conversations I had with particular people who were detained. Some people get extremely depressed; they just close themselves down and develop a kind of desperation. That desperation often takes the form of just going over and over the procedural details of their cases with anyone who will listen. In other cases there’s a kind of hopelessness that develops from the utter isolation of being a prisoner. Prisoners might develop unrealistic hopes about what an article in the paper or a court decision might do for them. Other detainees became extremely angry — I remember a woman from Uganda who was indignant that all these immigration officials thought that, just because she was from Africa, she was uneducated, which she certainly wasn’t.

I talked to other people who were extremely clear-eyed and realistic about what anyone could do for them. I’m thinking of a long-term Mariel Cuban detainee who just said, “Look, you’re going to leave here and you’re going to write about this and that’s fine, but we have nowhere to go.” And he was just stating reality as clearly as he could. As time went by and I heard from different prisoners, I was very moved by ones who would write and simply wanted to do what they could to let people know about what was going on. As one prisoner said to me, “America’s a big country, and someone will do something if you let people know”

MJ.com In your investigations you ran across a number of attempts by INS officials to stonewall media inquiries. Do you think this is a function of bureaucratic inefficiency, or is it an actual, concerted effort by the department to conceal what is going on?

I think it’s a combination. The immigration service has long had a culture of secrecy, which was mostly discovered after 9/11. Robert Kahn, who wrote a book entitled “Other People’s Blood,” about immigration detention during the Reagan years, described holding a particular document in his hands while discussing it with an INS official who was denying the existence of that document. It’s almost a bizarre parody of government secrecy. But at the same time it’s important to realize that there’s very intentional disinformation within immigration service and now coming from Homeland security in terms of immigration detention.

MJ.com: How widespread within the bureaucracy of the system is the awareness of what’s going on?

MD: Let me tell a story that should give a sense of how much awareness there is. In my book I describe a hunger strike by Egyptian detainees held in Alabama. The local jailers had gone to the district court for what’s known as a “force feed” order. Several high-ranking Justice Department litigators got involved, and around this time a newsletter emerged, which came from the Office of Immigration Litigation. In one of the articles, Paul Kovac wrote that an alien’s constitutional status in this country might be something that the government can use when an alien detainee challenges his or her treatment in detention. This is astonishing, and disturbing, because it tells me that high-ranking Justice Department officials know about the treatment of these detainees, but instead of trying to do something about the conditions, they’re looking for a way to justify those conditions.

MJ.com: You mentioned that after 9/11 there was pressure by the Justice Department to look like they were doing something, by rounding as many people as they could find.

MD: Yeah. I quote from a letter from FBI agent Colleen Rowley. This letter has an amazing little paragraph in it where she expresses concern over the pressure from FBI offices to round up Arabs in order to fill the detention centers. Likewise, Ashcroft repeatedly used the term “terrorist” to describe the people who were being detained, when he was certainly in a position to know that they were not terrorists.

MJ.com How has the increasingly common use of private prisons affected things?

MD: It has certainly added to the invulnerability of the agency. The use of private prison companies provides another level of deniability, a theory with which immigration officials familiar with the system have agreed. I’ll also mention that the Correctional Corporation of America, which contracts with the U.S. government to run a lot of immigration detention centers, has warned its shareholders of the dangers of public scrutiny. So that attitude dovetails very nicely with INS operations.

MJ.com: In what ways do you think the media could cover the subject better or more incisively?

MD: Here’s one. My book was criticized recently for spending too much time describing the runaround I would get from immigration officials. And I can understand in terms of journalism that you just want to focus on the story and not the process. But at a certain point it became important to me to describe the ways in which the people running the detention system tried to keep it hidden. An INS official tells me that i can’t interview one of its prisoners because of the orange or yellow alert but call back in a few weeks and i call back but now i’m not allowed to interview the prisoner because of the detention standards and so i say what do you mean? What detention standards? And I’m told to put my question in writing, and months go by, and the answer never comes. I can understand how those details might not be what people want to read, but I want people to understand how the system operates with such a lack of accountability and remains so secretive.

Also, in my book I quote a Fox News commentator who criticizes post-9/11 media coverage of immigrations detentions, saying that the liberal media was running “sob story cookie cutter” pieces. I actually agree with this commentator — the liberal media is perhaps too invested in these isolated human interest stories. But if you begin to link them altogether, you realize there’s a pattern here. None of this is an accident. There are 23,000 people in this system, and no one seems to know about it.